“There are some interesting analogies between the careers of Thaddeus Stevens and Abraham Lincoln,” noted Stevens biographer Ralph Korngold. One is that while both detested slavery, both were guilty — Stevens in 1821, Lincoln in 1847 — of appearing in court on behalf of a slaveholder against a fugitive slave woman. Lincoln’s case was more serious, since it involved the liberty not only of the woman, but of her six children, and since it was known that her Kentucky owner wished to sell her in the deep South. Lincoln, however, lost his case, while Stevens won his.”1

There were other similarities between the two men. Like Mr. Lincoln, Stevens lost a parent early in life. Like Mr. Lincoln, he had a pious and revered mother. Like Mr. Lincoln, Stevens supported the Second National Bank. Like Mr. Lincoln, he had a particular concern for the powerless. Like Mr. Lincoln, he was deprived of a presidential appointment he thought he deserved. Like Mr. Lincoln, he was several times denied the Senate seat he craved. Like Mr. Lincoln, he was a gifted politician. Stevens, however, used his gifts primarily as a floor manager of legislation.

But, noted fellow Pennsylvanian Alexander K. McClure, “Abraham Lincoln and Thaddeus Stevens were strangely mated. Lincoln as President and Stevens as Commoner of the nation during the entire period of our sectional war assumed the highest civil responsibilities in the administrative and legislative departments of the government. While Lincoln was President of the whole people, Stevens, as Commoner, was their immediate representative and oracle in the popular branch of Congress when the most momentous legislative measures of our history were conceived and enacted. No two men were so much alike in all the sympathy of greatness for the friendless and the lowly, and yet no two men could have been unlike in the methods by which they sought to obtain the same great end. Lincoln’s humanity was one of the master attributes of his character, and it was next to impossible for him to punish even those most deserving of it. In Stevens humanity and justice were singularly blended, and while his heart was ever ready to respond to the appeal of sorrow, he was one of the sternest of men in the administration of justice upon those who had oppressed the helpless. No man pleaded so eloquently in Congress for the deliverance of the bondmen of the South as did Stevens, and he made ceaseless battle for every measure needed by ignorant freedmen for the enjoyment of their rights obtained through the madness of Southern rebellion; and there was no man of all our statesmen whose voice was so eloquent for the swift punishment of the authors of war.”2

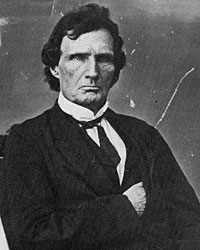

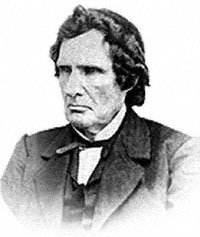

But there was a major difference in their temperaments. Thad Stevens, according to historian Donald Barr Chidsey, “was an island of ill-nature in a monotonous expanse of professional amiability; like [Roscoe] Conkling he didn’t ask that anybody like him, or even admire him, but he demanded that his associates fear and obey him — and they did.”3Unlike Mr. Lincoln, Stevens never lost his taste for invective. Throughout his life, he seemed embittered by failure to achieve the preeminence he thought he deserved. His zealous and nasty disposition won him many enemies. He was born with a club foot and later suffered an attack of “brain fever” that left him bald and in need of a wig. Bitterly sarcastic, quarrelsome and vindictive, inclined always to opposition, he was also personally generous. He strayed from his mother’s religious habits but remained a proselytizing teetotaler (although he occasionally indulged himself). His vice was gambling — which was his evening recreation. He also gambled in politics — putting everything he could on the politician he backed. His other loves were riding and reading and the Caledonia Iron Works, which he owned.

Thaddeus Stevens was born in Vermont in 1792 — one of four sons. His father was an alcoholic who eventually abandoned the family. His mother, a pious Baptist, wanted her son to become a minister. Stevens went to Dartmouth College from which he was expelled, attended Burlington College, and eventually returned to Dartmouth. He taught briefly and read law before moving to Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in 1816. His local notoriety and subsequent good fortune stemmed from a successful insanity defense of a farmhand who used scythe to detach the head of a fellow worker. With the profits from his legal business, he invested in real estate (which he often picked up at sheriff’s sales) and provided the venture capital for a charcoal-iron furnace.

Although his nickname was later the “Great Commoner,” as an attorney and legislator, he frequently found opportunities to help favored bankers and businessmen — and consistently favored the high tariff that Pennsylvania businesses required. In order to preserve the economic privileges of himself and his friends, he became chairman of the Canal Commissioners so that he could use that position to collect funds for Governor [Joseph] Ritner’s reelection. He spent money liberally and unsuccessfully tried to manipulate the results to Ritner’s advantage. The Democratic victory resulted in a Democratic investigation of Stevens’ election chicanery. An allegation of paternity outside marriage led to his dismissal from the House.

Stevens entered politics as an anti-Mason (after rejecting a proposed political collaboration by future President James Buchanan). His opposition to secret societies perhaps reflected his rejection by Phi Beta Kappa at Dartmouth, his aggravation with any form of elitism, and the Masons’ prohibition against membership by “cripples.” He was elected to his first of seven terms in the Pennsylvania Legislature in 1832 and quickly became a proponent of public education. He coalesced with the Whigs in 1835 to elect Whig Joseph Ritner as Governor. As a leader of the Pennsylvania House, he helped recharter the Bank of the United States through political techniques that appear to have involved buying certain members. Like Mr. Lincoln, Stevens used his legislative position to agitate for internal improvements — but in his case they were very specific improvements which involved the extension of railroad routes to Gettysburg to service his perpetually unprofitable iron works (first the Maria Furnace and later the Caledonia Furnace). After 1836, he switched his political target from Masons to slaveholders. He rose to legendary political stature by organizing the Whigs and anti-Masons at the 1837 Constitutional Convention although he did not accomplish what he might have had his attentions been focused.

Stevens worked hard for the election of William Henry Harrison in 1840, but was denied a promised appointment to the Cabinet. (He was a persistent opponent of the Clay faction of the Whigs.) In 1842, he left Gettysburg for Lancaster’s better business opportunities and to finance the debts on his iron works, but Lancaster’s Whigs were never thrilled by his emigration to their city. After boosting Winfield Scott for President in 1848, Stevens ran for Congress and won. He quarreled with Sen. James Cooper, the Whig who was elected to the Pennsylvania Senate seat Stevens himself coveted. He served in Congress without particular distinction until 1854 when he declined to seek reelection to the House.

Strongly abolitionist, he defended runaway slaves for free and fought tirelessly for racial equality, but equivocated on black suffrage after the Civil War (although he had been an early proponent of black suffrage in Pennsylvania). He did, however, join the Know-Nothing movement despite its status as a secret society. Biographer Hans L. Trefousse wrote that “because of its potential for strengthening the antislavery cause with additional votes, he did not hesitate to cooperate with the Know-Nothings, just as he had with their predecessors in the 1840s.”4

At 66 in 1858, he was once again elected to Congress. At a time when most men are retiring from active life, he began his most influential political phase. He backed Judge John McLean at the 1860 Chicago Republican convention, sought reelection but set his political sights again on a Senate seat. He failed in thatand his effort to replace Simon Cameron as Pennsylvania’s man in the Cabinet. His greatest political success was the election in December 1861 of his Pennsylvania ally, Galusha Grow, as speaker of the House of Representatives.

Pennsylvania journalist Alexander K. McClure wrote of Congressman Stevens and President Lincoln: “These two great civil leaders were not in close personal relations. Stevens was ever impatient of Lincoln’s tardiness, and Lincoln was always patient with Stevens’ advanced and often impracticable methods. Stevens was a born dictator in politics; Lincoln a born follower of the people, but always wisely aiding them to the safest judgment that was to be his guide. When Stevens proposed the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia, and followed it with the extension of the elective franchise to the liberated slaves, very many of his party followers in the House faltered and threatened revolt, and only a man of Stevens’ iron will and relentless mastery could have commanded a solid party vote for the measures which were regarded by many as political suicide. I sat by him one morning in the House before the session had opened when the question of negro suffrage in the District of Columbia was about to be considered, and I heard a leading Pennsylvania Republican approach him to protest against committing the party to that policy. Stevens’ grim face and cold gray eye gave answer to the man before his bitter words were uttered. He waved his hand to the trembling suppliant and bad him go to his seat and vote for the measure or confess himself a coward to the world. The Commoner was obeyed, for had disobedience followed the offender would have been proclaimed to his constituents, over the name of Stevens, as a coward, and that would have doomed him to defeat.”5

Stevens biographer Fawn M. Brodie wrote: “Stevens’ impatience and pessimism blinded him to the President’s true intentions. He believed Lincoln to be ‘honest’ and ‘amiable,’ but misled by Seward, Weed, and the border-state men, particularly Montgomery Blair. He described him with irony as ‘our very discreet Executive,’ having no suspicion that Lincoln was being driven by what the President himself described later to a young cavalryman as ‘a great impulse moving me to do justice to five or six millions of people.’ This was something, in fact, that very few men were ever permitted to see.”6

Stevens could be an astute politician, but he could also waste his energies on unimportant fights. He became embroiled in personal disputes with other members of Congress, including with erstwhile ally Elihu Washburne over an appropriation for a canal. Stevens blocked the pork barrel project. Washburne had his opportunity for retribution when Grow was defeated for reelection in 1862 and Schuyler Colfax was elected speaker. Colfax offered Washburne the Ways and Means chairmanship, but the Illinois Congressman declined in deference to Stevens.

Thaddeus Stevens did not abide fools or cowards with anything less than disdain. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “One powerful figure, in a speech long remembered, struck not only at the Congressional minority but at the Administration. When Thad Stevens rose to assail the contention of Representative A. B. Olin of New York that the rebellious States were still inside the Union, and that their loyal people were entitled to its full protection, he took issue with Lincoln as well. Stevens at least subconsciously cherished a resentful belief that he and not Cameron should have sat for Pennsylvania in the Cabinet. He never saw Lincoln when he could help it, and never spoke cordially of him. While close to Chase, whom he had known for full twenty years and with whom he worked closely in meeting the financial needs of the nation, he felt contempt for Seward, and dislike for Montgomery Blair. It would have been well had Stevens devoted himself exclusively to financial affairs; but this iron-willed man held deep convictions about the war, in which force must be used to the utmost, and about the peace, in which the North must show no softness, no spirit of compromise, no magnanimity. In brooding over what he regarded as Lincoln’s delays and excessive generosity, Stevens sometimes exhibited a frenzy of anger.”7

As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee, he was the effective leader of the House and a constant thorn in the side of Secretary of the Treasury Chase on financing the nation’s war debt. He was a proponent of District of Columbia emancipation and use of black soldiers, but he lost many battles — even over matters controlled by his own committee. He thought Mr. Lincoln legally wrong in his April 19, 1861 “blockade” of Southern ports, arguing that the authorization of the cities as ports of entry should simply have been revoked. Lincoln’s actions, he felt, recognized the Confederacy as a separate nation. Given that presidential faux pas, Stevens felt all restrictions on punitive Union action toward the South were removed.

Those actions clearly included emancipation of slaves. Biographer Fawn M. Brodie wrote: “In November 1861 Stevens introduced a bill providing for total emancipation. It did not pass. On December 2 he introduced a resolution asking Lincoln to free every slave who aided in the rebellion, with compensation for loyal masters. Lincoln in the same week, much behind Stevens, delicately suggested in his Message to Congress that the border states agree to abolish slavery by 1900, selling their slaves to the government, which would then provide for their emancipation and colonization.”8 Historian George H. Mayer wrote: “It would take four years for public opinion to catch up to Stevens.”9

Biographer Samuel W. McCall wrote that Stevens “accused the administration of being under the influence of ‘Kentucky councilors,’ so far as the employment of slaves in the war was concerned. He did not believe in keeping the runaway slaves employed in some menial work until the war was over, in order then to send them back to their masters ‘unhurt, under the fugitive slave law.’ He declared that he was in favor of sending the army through the slave populations of the South and asking them ‘to come from their masters, to take the weapons which we furnish, and to join us in this war of freedom.’ He denounced the charges that the blameless sons of Ethiopia’ were inhuman soldiers.”10

Biographer Fawn M. Brodie wrote: “Both Abraham Lincoln and Thaddeus Stevens passionately desired to see an end to slavery. But Lincoln, a strict constitutionalist, who had always declared himself to be antislavery but not an abolitionist, could not for some time be persuaded that the outbreak of war had given him any special power to destroy. Moreover, he was desperately intent upon holding the slave-holding areas still loyal to the Union — Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and portions of Missouri, Virginia, and Tennessee.”11 Even among abolitionists, Stevens had critics. “Because Stevens so seldom lapsed into the flowery idealism of [Charles] Sumner and [William Lloyd] Garrison, the militant Abolitionists suspected that he was motivated more by dislike of rebels than devotion to the Negro,” wrote historian George H. Mayer.12

Stevens had little patience for half-steps. When President Lincoln sent Congress a proposal for compensated emancipation in March 1862, Stevens denigrated it. Biographer McCall wrote: “On March 10, Mr. Roscoe Conkling introduced a resolution the precise terms of that recommended by the President, and it was passed by a vote of 89 to 31. Stevens voted for it, but he regarded it as of very little importance. On a motion to postpone, he said he could not see why one side was ‘so anxious to pass it, or the other side ‘so anxious to defeat it. I think it is about the most diluted milk-and water gruel proposition that was ever given to the American nation. (Laughter.) The only reason I can discover why any gentleman should wish to postpone this measure is for the purpose of having a chemical analysis to see whether there is any poison in it. (Laughter).'”13

Republican Editor Alexander K. McClure, who came from the same area of Pennsylvania as Stevens, observed that Stevens “could not but appreciate Lincoln’s generous forbearance even with all of Stevens’ irritating conflicts, and Lincoln profoundly appreciated Stevens as one of his most valued and useful co-workers, and never cherished resentment even when Stevens indulged in his bitterest sallies of wit or sarcasm at Lincoln’s tardiness. Strange as it may seem, these two great characters, even in conflict and yet ever battling for the same great cause, rendered invaluable service to each other, and unitedly rendered incalculable service in saving the Republic. Had Stevens not declared for the abolition of slavery as soon as the war began, and pressed it in and out of season, Lincoln could not have issued his Emancipation Proclamation as early as September, 1862. Stevens was ever clearing the underbrush and preparing the soil, while Lincoln followed to sow the seeds that were to ripen in a regenerated Union; and while Stevens was ever hastening the opportunity for Lincoln to consummate great achievements in the steady advance made for the overthrow of slavery, Lincoln wisely conserved the utterances and efforts of Stevens until the time became fully ripe when the harvest could be gathered. I doubt not that Stevens, had he been in Lincoln’s position, would have been greatly sobered by the responsibility that the President must accept for himself alone, and I doubt not that if Lincoln had been a Senator or Representative in Congress, he would have declared in favor of Emancipation long before he did it as President. Stevens as Commoner could afford to be defeated, to have his aggressive measures postponed, and to take up the battle for them afresh as often as he was repulsed; but the President could proclaim no policy in the name of the Republic without absolute assurance of its success. Each in his great trust attained the highest possible measure of success, and the two men who more than all others blended the varied currents of their efforts and crystallized them in the unchangeable policy of the government were Lincoln and Thaddeus Stevens.”14

Biographer Ralph Korngold wrote: “Thaddeus Stevens kept away from the White House and the departmental offices. Stubbornly, even belligerently, independent, he would have regarded friendly calls on the President as a fawning on power. He wished to be free to attack Cabinet officers with incisive criticism. He had bitterly resented the appointment of Cameron to the War Department, regarding himself as better Cabinet material and coveting the Treasury. He thought Lincoln too tardy, too ready to temporize and compromise, too anxious to consult public sentiment. As yet, however, he was willing to restrain his impatience and cooperate energetically with Administration leaders.’15

Policy and temperament separated the two men. Biographer Ralph Korngold wrote: “Lincoln believed that the Union could best be saved by having the federal government interfere with slavery as little as possible; Stevens believed it could best be saved by vigorously attacking and destroying the institution. Lincoln believed that the Negro was unassimilable, a stranger in a strange land, and must eventually emigrate or be deported; Stevens believed that he was an integral part of the American nation and that national policy must be shaped accordingly. Stevens advocated his antislavery measures from conviction; Lincoln adopted them from necessity. The delay in their application, occasioned by Lincoln’s resistance, may well have been salutary, but it should be considered that when Stevens advocated the measures he undoubtedly took the President’s resistance into account, as he took into account the time required to mold public opinion for their acceptance.”16

In August 1863, he visited Mr. Lincoln at the White House with Cameron and told the President, “In order that we may be able in our state to go to work with a good will, I want you to make us one promise, that you will reorganize your cabinet and leave Montgomery Blair out of it.” Lincoln declined to do so and Stevens declined to support Lincoln’s renomination, saying later: “If the Republican party desires to succeed, they must get Lincoln off the rack and nominate a new man.”17 Pennsylvania political leader Alexander McClure wrote: “Stevens, the Great commoner of the war, while sincerely desiring Lincoln’s re-election because he hated McClellan worse than he hated Lincoln, and because he felt that the election of Lincoln was necessary to the safety of the Union, was intensely bitter against Lincoln personally, and rarely missed an opportunity to thrust his keenest invectives upon him.”18

Stevens was unstinting in his concern for the welfare of former slaves — and probably personally did as much as any political leader of his generation. A bachelor, he lived with his mulatto housekeeper who was commonly believed to be his mistress — but their public relationship was very decorous and he always treated her with the greatest respect. Biographer Fawn M. Brodie observed: “Stevens and Lincoln both treated individual Negroes as equals and as friends, without self-consciousness or self-righteousness. But Stevens never agreed with Lincoln about the necessity or justice of colonizing all the Negroes abroad, and Lincoln eventually came to recognize the idea as largely impracticable, though he never completely abandoned it.”19

Footnotes

- Ralph Korngold, Thaddeus Stevens, p. 44.

- Alexander K. McClure, Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 277-278.

- Donald Barr Chidsey, The Gentleman from New York: A Life of Roscoe Conkling, p. 1, 4-5.

- Hans. L. Trefousse, Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian, p. 89.

- Alexander K. McClure, Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 280-281.

- Fawn M. Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, p. 159.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 340-341.

- Fawn M. Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, p. 155.

- George H. Mayer, The Republican Party, 1854-1964, p. 112-113.

- Samuel W. McCall, Thaddeus Stevens, p. 216.

- Fawn M. Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, p. 154.

- George H. Mayer, The Republican Party, 1854-1964, .

- Samuel W. McCall, Thaddeus Stevens, p. 216-217.

- Alexander K. S., Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 284-285.

- Ralph Korngold, Thaddeus Stevens: A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great, p. 224.

- Ralph Korngold, Thaddeus Stevens: A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great, p. 224-225.

- Hans. L. Trefousse, Thaddeus Stevens: Nineteenth-Century Egalitarian, p. 202.

- Alexander K. McClure, Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 126.

- Fawn M. Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, .