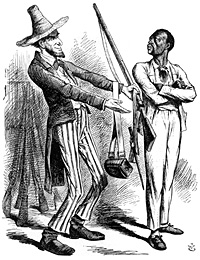

Historian John Hope Franklin wrote that at the beginning of the Civil War : “When Negroes rushed to offer their services to the Union, they were rejected. In almost every town of any size there were large numbers of Negroes who sought service in the Union army; failing to be enlisted they bided their time and did whatever they could to assist.”1

Historian Susan-Mary Grant wrote “that when hostilities commenced between North and South in 1861 blacks throughout the North, and some in the South too, sought to enlist. However, free blacks in the North who sought to respond to Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers found that their services were not required by a North in which slavery had been abolished but racist assumptions still prevailed. Instead they were told quite firmly that the war was a ‘white man’s fight’ and offered no role for them. The notable northern black leader, Frederick Douglass, himself an escaped slave, summed the matter up succinctly:”2

Colored men were good enough to fight under Washington. They are not good enough to fight under McClellan. They were good enough to fight under Andrew Jackson. They are not good enough to fight under Gen. Halleck. They were good enough to help win American Independence but they are not good enough to help preserve that independence against treason and rebellion. They were good enough to defend New Orleans but not good enough to defend our poor beleaguered Capital.3

The move to reverse that military deficiency came slowly – moving into full gear only in the spring of 1863. Historian Benjamin P. Thomas wrote: “Although Lincoln announced the proposed use of colored troops in the Emancipation Proclamation, he had not come easily to that decision. The act of July 17, 1862 gave him complete discretion in the employment of Negroes for any purpose whatsoever, but he had shrunk from using black men to kill white men. To deprive the South of the services of her slaves was a legitimate and necessary war measure. To use colored men as teamsters and laborers in the Union army would release white men for combat. But to put weapons in the hands of black men, some of whom might become frenzied with the flush of new-found freedom, was a matter of most serious consequence.”4

Mr. Lincoln was clearly worried about the reaction among white soldiers – particularly those soldiers from Border States. In the spring of 1862, Mr. Lincoln met with a group of Republican Senators including Iowa’s James Harlan. Historian Ida M. Tarbell wrote: “The senators went to Mr. Lincoln to urge upon him the paramount importance of mustering slaves into the Union army. They argued that as the war was really to free the negro, it was only fair that he should take his part in working out his own salvation. Mr. Lincoln listened thoughtfully to every argument, and then replied:

Gentlemen, I have put thousands of muskets into the hands of loyal citizens of Tennessee, Kentucky, and Western North Carolina. They have said they could defend themselves, if they had guns. I have given them the guns. Now, these men do not believe in mustering in the negro. If I do it, these thousands of muskets will be turned against us. We shall lose more than we should gain.5

Tarbell added: “The gentlemen urged other considerations, among them that it was not improbable that Europe, which was anti-slavery in sentiment, but yet sympathized with the notion of a Southern Confederacy, preferring two nations to one in this country, would persuade the South to free her slaves in consideration of recognition. After they had exhausted every argument, Mr. Lincoln answered them.

“Gentlemen, he said, ‘I can’t do it. I can’t see it as you do. You may be right, and I may be wrong; but I’ll tell you what I can do; I can resign in favor of Mr. Hamlin. Perhaps Mr. Hamlin could do it.”6

According to Tarbell, the Senators were shocked that President Lincoln would consider turning over the reins of government to Vice President Hannibal Hamlin.7 Although Mr. Lincoln was publicly cautious, he was slowly moving to a bolder position which would eventually employ about 180,000 black soldiers. The duality of the President’s thinking was demonstrated when he wrote General David Hunter in early April, 1862 about the use of black troops in Hunter’s military command. Hunter had long been an advocate for recruitment of such troops and had recruited two regiments in the Sea Islands he controlled off South Carolina. President Lincoln: “I am glad to see the accounts of your colored force at Jacksonville, Florida. I see the enemy are driving at them fiercely, as is to be expected. It is important to the enemy that such a force shall not take shape, and grow, and thrive, in the South; and in precisely the same proportion, it is important to us that it shall. Hence the utmost certain caution and vigilence [sic] is necessary on our part. The enemy will make extra efforts to destroy them; and we should do the same to preserve and increase them.”8

Historian John T. Hubbell wrote: “In April and May [1862], the new Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton, encouraged (at least implicitly) the arming of blacks in South Carolina. The situation there caused a great stir, because the general in command, David Hunter, proved to be politically inept and hence a political liability. He managed to offend many officers and men in the white regiments as well as two congressmen of a border state, Kentucky. When those congressmen demanded explanations of what was transpiring in South Carolina. Stanton retreated into his bureaucratic defenses but did ask General Hunter for a report, which he forwarded to Congress. Hunter’s report was entertaining to some Republicans (referring to ‘fugitive rebels’), and to the border state congressmen – insulting.”9

Lincoln biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay wrote: “General David Hunter was the pioneer in these experiments. Almost immediately after his arrival at the Department of the South he asked the Secretary of War for 56,000 muskets and ‘authority to arm such loyal men as I can find in the country,’ and with an eye to the seductive effects of a brilliant uniform, he added a request for ‘50,000 pairs of scarlet pantaloons,’ saying, ‘This is all the clothing I shall require for these people.'”10 Nicolay and Hay noted that “General Hunter’s experiment, however, was a greater parliamentary than military success. There was still too much prejudice in the army itself, and particularly among army officers, against such an innovation. The blacks did not come forward freely to enlist, and when the general undertook to compel them by drafting, it confirmed in their minds the stories which had been told them that it was a renewed slavery; that they were to be sold to Cuba; that they were to be placed in the front rank of battle for slaughter, and many other direful predictions. Under such conditions, though the regiment was formed, it was beset by desertion, by neglect, by contempt, and also by the fatal difficulty that under existing regulations the paymaster could not recognize it. From all these causes it languished, and was, with the exception of one company, formally disbanded about three months afterwards.”11

Historian Edward A. Miller, Jr., wrote: “Possibly because he thought he was not making himself clear, Hunter tried again to get Stanton’s attention on the black soldier question. This time he addressed the real issue, pay for the remaining members of the one regiment he had recruited. ‘Not satisfied that I shall be furnished with the means of making compensation to these loyal men for their services, and for the reason that their officers hold an anomalous position as men without commissions discharging the duties of commissioned officers. I desire earnestly to have a speedy and favorable decision upon the organization of the regiment.’ He said he had stopped active recruiting but was ready to put six regiments in the field in two months. Of course, the single unauthorized regiment was reported as ‘organized,…uniformed, and [drawing] its rations. The uniform consists of a dark blue coat, stripes or trimmings of any sort and no bright buttons.’ The regiment did not often appear under arms and was generally confined to labor service on the docks at Hilton Head. As before, Stanton declined to answer the request, and Hunter showed his frustration in a 10 August letter to Stanton, ‘Failing to receive authority to muster the First South Carolina Volunteers into the service of the United States, I have disbanded them.'”12 Hunter wrote a report for Congress in early June;

“I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of a communication from the Adjutant-General of the Army, dated June 13, 1862, requesting me to furnish you with the information necessary to answer certain Resolutions introduced in the House of Representatives June 9, 1862, on the motion of the Hon. Mr. [Charles A.] Wickliffe, of Kentucky; their substance being to enquire:

1st – Whether I had organized, or was organizing, a regiment of fugitive slaves’ in this department.

2d – Whether any authority had been given to me from the War Department for such an organization; and

3rd – Whether I had been furnished, by order of the War Department, with clothing, uniforms, arms, equipments, and so forth, for such a force?

Only have received the letter at a late hour this evening, I urge forward my answer in time for the steamer sailing to-morrow morning, – this haste preventing me from entering, as minutely as I could wish, upon many points of detail, such as the paramount important of the subject would seem to call for. But, in view of the near termination of the present session of Congress, and the wide-spread interest which must have been awakened by Mr. Wickliffe’s resolutions. I prefer sending even this imperfect answer to waiting the period necessary for the collection of fuller and more comprehensive data.

To the first question, therefore, I reply: That no regiment of ‘fugitive slaves’ has been, or is being, organized in this department. There is, however, a fine regiment of loyal persons whose late masters are fugitive rebels – men who everywhere fly before the appearance of the national flag, leaving their loyal and unhappy servants behind them, to shift, as best they can, for themselves. So far, indeed, are the loyal persons composing the regiment from seeking to evade the presence of their late owners, that they are now, one and all, endeavoring with commendable zeal to acquire the drill and discipline requisite to place them in a position to go in full and effective pursuit of their fugacious and traitorous proprietors.

To the second question, I have the honor to answer that the instructions given to Brig.-Gen T.W. Sherman by the Hon. Simon Cameron, late Secretary of War, and turned over to me, by succession, for my guidance, do distinctly authorize me to employ ‘all loyal persons offering their service in defence of the Union, and for the suppression of this rebellion,’ in any manner I may see fit, or that circumstances may call for. There is no restriction as to the character or color of the persons to be employed or the nature of the employment – whether civil or military – in which their services may be used. I conclude, therefore, that I have been authorized to enlist ‘fugitive slaves’ as soldiers, could any such fugitives be found in this department. No such characters, however have yet appeared within view of our most advanced pickets, – the loyal negroes everywhere remaining on their plantations to welcome us, aid us, and supply us with food, labor and information. It is the masters who have in every instance been the ‘fugitives,’ running away from loyal slaves as well as loyal soldiers; and these, as yet, we have only partially been able to see – chiefly their heads over ramparts, or dodging behind trees, rifles in hand, in the extreme distance. In the absence of any ‘fugitive master law,’ the deserted slaves would be wholly without remedy had not the crime of treason given them right to pursue, capture and bring those persons of whose benignant protection they have been thus suddenly and cruelly bereft.

To the third interrogatory, it is my painful duty to reply that I have never received any specific authority for issue of clothing, uniforms, arms, equipments and so forth, to the troops in question, – my general instructions from Mr. Cameron, to employ them in any manner I might find necessary, and the military exigencies of the department and the country, being my only, but I trust, sufficient justification. Neither have I have any specific authority for supplying these persons with shovels, spades, and pickaxes, when employing them as laborers; nor with boats and oars, when using them as lighter-men; but these are not points included in Mr. Wickliffe’s resolution. To me it seemed that liberty to employ men in any particular capacity implied and carried with it liberty, also, to supply them with the necessary tools; and, acting upon this faith, I have clothed[,] equipped, and armed the only loyal regiment yet raised in South Carolina, Georgia or Florida.

I must say, in vindication of my own conduct, that, had it not been for the many other diversified and imperative claims on my time and attention, a much more satisfactory result might to have been achieved; and that, in place of only one regiment, as at present, at least five or six well-drilled, and throughly acclimated regiments should, by this time, have been added to the loyal forces of the Union.

The experiment of arming the blacks, so far as I have made it, has been a complete and even marvellous [sic] success. They are sober, docile, attentive, and enthusiastic; displaying great natural capacities in acquiring the duties of the soldier. They are now eager beyond all things to take the field and be led into action; and it is the unanimous opinion of the offices who have had charge of them that, in the peculiarities of this climate and country, they will prove invaluable auxiliaries, fully equal to the similar regiments so long and successfully used by the British authorities in the West India Islands.

“In conclusion, I would say, it is my hope – there appearing no possibility of other reinforcements, owing to the exigencies of the campaign in the Peninsula – to have organized by the end of next fall, and be able to present to the government, from forty-eight too fifty thousand of these hardy and devoted soldiers.

Trusting that this letter may be made part of your answer to Mr. Wickliffe’s resolutions, I have the honor to be…13

General Hunter’s sarcastic report was duly transferred by the War Department to the House of Representatives where it was read by the clerk: “Here its effect were magical,” wrote historian Joseph T. Wilson. The clerk could scarcely read it with decorum; nor could half his words be heard amidst the universal peals of laughter in which both Democrats and Republicans appeared to vie as to which should be the more noisy. Mr. Wicklife, who only entered during the reading of the latter half of the document, rose to his feet in a frenzy of indignation, complaining that the reply, of which he had only heard some portion, was an insult to the dignity of the House, and should be severely noticed.” Congressman Wicklife’s colleagues, however, were more amused than outraged.14

Historian John T. Hubbell wrote that “as the curtain fell on Hunter, Stanton on August 25 authorized Brigadier General Rufus Saxton at Beaufort, South Carolina to ‘arm, uniform, equip, and receive into the service of the United States such number of volunteers of African descent as you may deem expedient, not exceeding 5,000.’ Why the reversal? Why had Stanton authorized Saxton to do what had been denied Hunter? A comment by Lieutenant Charles Francis Adams Jr. may be pertinent. Regarding Hunter, ‘Why could not fanatics be silent and let Providence work for awhile?’ (And if not providence, at least the President.) In short, had Hunter managed to be more politic with respect to his fellow officers and the Congress, had he been able to restrain his rhetorical flourishes, he may not have run afoul of the critics of his policy, to say nothing of the President. The fact was, blacks were now to be brought into the service, not by a general assembly, but by order of the War Department – and the President.”15

The nature of government policy had restrained the potential recruitment of black soldiers. Historian Joseph T. Wilson wrote:

The conduct of the Government in revoking Gen. Fremont’s Proclamation, and of McClellan’s with the Army of the Potomac, in catching and returning escaped slaves, also had a tendency for some time to keep back even the free negroes of Virginia and Maryland. But this class of people never enlisted to any great numbers either before or after 1863, and there finally came to be a general want of spirit with them, while with the slave class there was a ready enthusiasm to enlist. Senator Wilson, of Massachusetts, was Chairman of the Committee of Military Affairs, and reported from that committee on the 8th of July 1862, a bill authorizing the arming of negroes as a part of the army. The bill finally passed both houses and received the approval of the President on the 17th of July, 1862. The battle for its success is as worthy of record as any fought by the Phalanx. The debate was characterized by eloquence and deep feelings on both sides. Says an account of the proceedings in Henry Wilson’s ‘Anti-slavery Measures of Congress:

Mr. Sherman (Rep.) Of Ohio said, ‘The question arises, whether the people of the United States, struggle for national existence, should not employ these blacks for the maintenance of the Government. The policy heretofore pursued by the officers of the United States has been to repel this class of people from our lines, to refuse their services. They would have made the best spies; and yet they have been driven from our lines.’ – ‘I tell the President,’ said Mr. Fessenden (Rep.) Of Maine, ‘from my place here as a senator, I tell the generals of our army, they must reverse their practices and their course of proceeding on this subject ** I advise it here from my place, – treat your enemies as enemies, and avail yourselves like men of every power which God has placed in your hands to accomplish your purpose within the rules of civilized warfare.’ Mr. Rice, (war Dem.) Of Minnesota, declared that ‘not many days can pass before the people of the United States North must decide upon one of two questions: we have either to acknowledge the Southern Confederacy as a free and independent nation, and that speedily; or we have as speedily to resolve to use all the means given us by the Almighty to prosecute this war to a successful termination. The necessity for action has arisen. To hesitate is worse than criminal. Mr. Wilson said, ‘The senator from Delaware, as he is accustomed to do, speaks boldly and decidedly against the propostion. He asks if American soldiers will fight if we organize colored men for military purposes. Did not American soldiers fight at Bunker Hill with negroes in the ranks, one of whom shot down Major Pitcairn as he mounted the works? Did not American soldiers fight at Red Bank with a black regiment from your own State, sir? (Mr. Anthony in the chair.) Did they not fight on the battle-field of Rhode Island with that black regiment, one of the best and bravest that ever trod the soil of this continent? Did not American soldiers fight at Fort Griswold with black men? Did they not fight with black men in almost every battle-field of the Revolution? Did not the men of Kentucky and Tennessee, standing on the lines of New Orleans, under the eye of Andrew Jackson, fight with colored battalions whom he had summoned to the field, and whom with he thanked publicly for their gallantry in hurling back a British foe? It is all talk, idle talk, to say that the volunteers who are fighting the battles of this country are governed by any such narrow prejudice or bigotry. These prejudices are the results of the teachings of demagogues and politicians, who have for years undertaken to delude and deceive the American people, and to demean and degrade them.’

Mr. Grimes had expressed his views a few weeks before, and desired a vote separately on each of these sections. Mr. Davis declared that he was utterly opposed, and should ever be opposed, to placing arms in the hands of negroes, and putting them into the army. Mr. Rice wished ‘to know if Gen. Washington did not put arms into the hands of negroes, and if Gen Jackson did not, and if the senator has ever condemned either of those patriots for doing so.’ ‘I deny,’ replied Mr. Davis, ‘that, in the Revolutionary War, there ever was any considerable organization of negroes. I deny, that, in the war of 1812, there was ever any organization of negro slaves. * * * In my own State, I have no doubt that there are from eighty to a hundred thousand slaves that belong to disloyal men. You propose to place arms in the hands of the men and boys, or such of them as are able to handle arms, and to manumit the whole mass, men, women, and children, and leave them among us. Do you expect us to give our sanction and our approval to these things? No, no! We would regard their authors as our worst enemies; and there is no foreign despotism that could come to our rescue, that we would not joyously embrace, before we would submit to any such conditions of things as that. But, before we had invoked this foreign despotism, we would arm every man and boy that we have in the land, and we would met you in a death-struggle, to overthrow together such an oppression and our oppressors.’ Mr. Rice remarked in reply to Mr. Davis, ‘The rebels hesitate at nothing. There are no means that God or the Devil has given them that they do not use. The honorable senator said that the negroes might be useful in loading and swabbing and firing cannon. If that be the case, may not some of them be useful in loading, swabbing, and firing the musket?’16

President Lincoln did not rush to employ blacks in these capacities in 1862. Historian George H. Mayer wrote: “During July, Congress dealt once more with the disturbing slavery issue by passing the Second Confiscation Act, granting freedom to the slaves of all persons resisting the Union where such blacks came under the cognizance of the military arm of the government. It also authorized the President to employ as many negroes as he deemed necessary to suppress the rebellion in any capacity most likely to promote the public welfare. Lincoln considered the law of doubtful constitutionality, and he hesitated to utilize its most drastic provisions, especially with respect to arming blacks for military purposes.”17

After the passage of the Second Confiscation Act, according to historian Frederic Bancroft , “on July 21st and 22d [1862], the President laid before his Cabinet different questions concerning a more aggressive war policy. Among other points, all agreed that it would be well to permit the use of negroes as military laborers; but Lincoln was unwilling that they should be enlisted as soldiers, as General [David] Hunter has recommended.”18 However, noted Lincoln biographers John Nicolay and John Hay, “In resorting to the policy of general military emancipation, President Lincoln did not mean to rely upon its merely sentimental effect. From the time when the necessities of war forced upon him the adoption of that policy it was coupled with the expectation of making it bring to the help of the Union armies a powerful contingent of negro soldiers. We find from several entries in the dairy of Secretary [of the Treasury Salmon P.] Chase that this course was foreshadowed at the Cabinet meetings following that of July 22, 1862, when he submitted the first draft of his emancipation proclamation. While the time had not yet, in his judgment, arrived for a general arming of the blacks, he nevertheless indicated an intention to organize and use a military force of negroes for a specific object.”19

Pressure for the use of black soldiers was indeed growing in the Cabinet. At the August 3 Cabinet meeting Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase proposed that freed slaves be organized into military companies. Secretary Chase wrote in his diary:

The question of arming slaves was then brought up and I advocated it warmly. The President was unwilling to adopt this measure, but proposed to issue a Proclamation, on the basis of the Confiscation Bill, calling upon the States to return to their allegiance – warning the rebels the provisions of the Act would have full force at the expiration of sixty days – adding, on his own part, a declaration of his intention to renew, at the next session of Congress, his recommendation of compensation to States adopting the gradual abolishment of slavery – and proclaiming the emancipation of all slaves within States remaining in insurrection on the first of January, 1863.

I said that I should give to such a measure my cordial support, but I should prefer that no new expression on the subject of compensation should be made, and I thought that the measure of Emancipation could be much better and more quietly accomplished by allowing Generals to organize and arm the slaves (thus avoiding depredation and massacre on the one hand, and support to the insurrection on the other) and by directing the Commanders of Departments to proclaim emancipation within their Districts as soon as practicable; but I regarded this as so much better than inaction on the subject, that I should give it my entire support.

The President determined to publish the first three Orders forthwith, and to leave the other for some further consideration. The impression left upon my mind by the whole discussion was, that while the President thought that the organization, equipment and arming of negroes, like other soldiers, would be productive of more evil than good, he was not unwilling that Commanders should, at their discretion, arm, for purely defensive purposes, slaves coming within their lines.

Mr. Stanton brought forward a proposition to draft 50,000 men. Mr. Seward proposed that the number should be 100,000. The President directed that, whatever number were drafted, should be a part of the 300,000 already called for. No decision was reached, however.20

About the same time, Kansas Senator James H. Lane led a delegation to the White House to meet Mr. Lincoln. The New York Tribune reported:

A deputation of Western gentlemen waited upon the President this morning….The President received them courteously, but stated to them that he had not prepared to go the length of enlisting negroes as soldiers. He would employ all colored men offered as laborers, but would not promise to make soldiers of them.

The deputation came away satisfied that it is the determination of the Government not to arm negroes unless some new and more pressing emergency arises. The President argued that the nation could not afford to lose Kentucky at this crisis, and gave it as his opinion that to arm the negroes would turn 50,000 bayonets from the loyal Border States against us that were for us.

Upon the policy of using negroes as laborers, the confiscation of Rebel property, and the feeding of National troops upon the granaries of the enemy, the President said there was no division of sentiment. He did not explain, however, why it is that the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Virginia carry out this policy so differently. The President promised that the war should be prosecuted with all the rigor he could command, but he could not promise to arm slaves or to attempt slave insurrections in the Rebel States. The recent enactments of Congress on emancipation and confiscation he expected to carry out.21

Historian Allan Nevins described what was apparently the same meeting: “Reports also spread of a colloquy between Lincoln and a Western delegation, including a couple of Senators, who had called to offer two Negro regiments – which under the new confiscation law he was empowered to accept. The President told them that he was ready to employ Negro teamsters, cook, pioneers, and the like, but not soldiers. A warm discussion followed, which Lincoln was said to have closed with the words: ‘Gentlemen, you have my decision. It embodies my best judgment, and if the people are dissatisfied, I will resign and let Mr. Hamlin try it.’ Such heat had been generated that one caller exclaimed: ‘I hope, in God’s name, Mr. President, you will!'”22

Mr. Lincoln was always worried about the impact of his actions on Border States. Historian John T. Hubbell wrote: “During the summer of 1862, Lincoln evinced no inclination to support Hunter, to implement the provisions of the second Confiscation Act liberating the slaves of Rebels, or to employ blacks other than as laborers. He stated his views to the cabinet in late July, and on August 6 he told a delegation of ‘Western gentlemen’ that he would not arm blacks ‘unless some new and more pressing emergency arises.’ Such, he said, would turn ‘50,000 bayonets’ in the border against the Union. Steps short of actually arming blacks would be continued – upon this he and his critics did not differ.”23 But noted Nicolay and Hay, there were other considerations which weighed on Mr. Lincoln:

The whole history of this first experiment but repeats the constant lesson, that statesmen, generals, and reformers must always and unavoidably reckon with public opinion when they undertake to change either for worse or for better the complex machinery of modern society and government. The failure of Hunter’s regiment was only temporary; it furnished the germ of later success. One company, under command of Sergeant C.T. Trowbridge as acting captain, held together in spite of all discouragement and neglect, and when General Saxton received the already mentioned orders of the Secretary of War, dated August 25, 1862, to organize five thousand volunteers of African descent, it became the first company of the First South Carolina Volunteers, a regiment the formation of which was begun on the 7th of November. T. W. Higginson, of Massachusetts, was appointed its colonel, and took command about the 1st of December. Even then recruiting was slow. The regiment numbered five hundred when Colonel Higginson took command, and six weeks or more elapsed before it was completed.24

It took two years of Civil War for the Union government actively to begin actively recruiting black soldiers. President Lincoln opened the door in his final Emancipation Proclamation which stated: “I further declare and make known that such persons of suitable condition will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts, in said service.”25 Historian John Hubbell wrote: “Lincoln acted as he did from necessity. His almost mystical devotion to the Union and his personal compassion for the dispossessed of the world combined into policy. Events moved him in the sense that events determined the time for action. During the Civil War a basic truth emerged: Black people understood the meaning of the war and contributed to the great goal of freedom. Yet blacks were also objects; in order to defeat the white South, the white North needed black men. Lincoln was their emancipator, their savior, when he spoke as the cautious, prudent political leader and when he eloquently spoke of the magnificent contribution that black soldiers made to the Union.”26

Once the final Emancipation Proclamation had been issued on January 1, 1863, the barriers to black recruitment began to fall. One impetus was Vice President Hannibal Hamlin. In his biography of his grandfather, Charles Eugene Hamlin wrote:

When the project of arming the colored men was discussed among the friends of the administration, Mr. Hamlin set about quietly to ascertain the sentiments of young and ambitious Union officers of his acquaintance. There were several who were peculiarly close to him, for two were his elder sons, and a third was the son of his friend and neighbor, John Appleton, the distinguished chief justice of Maine. Mr. Hamlin’s sons enlisted in 1862. Charles, the elder, went out as a major of the Eighteenth Maine, and Cyrus as captain and aide on the staff of General Fremont. John F. Appleton was one of the college friends and associates of the Hamlin brothers. He was of that type of the American college man and soldier exemplified in Charles Russell Lowell, Robert Gould Shaw, and Theodore Winthrop. While Major Charles Hamlin favored the enlistment of the negroes, he preferred what proved to be a more active service in the field, and remained in the Army of the Potomac as adjutant-general of Hooker’s division. Both Captain Hamlin who had served in West Virginia, and Captain Appleton who had been sent farther south, saw enough of the negro to convince them that he had good fighting qualities, and knowing the opinions of the Vice-President they wrote him freely. Captain Hamlin was by nature ardent and enthusiastic, and when he made up his mind to carry an undertaking through he embraced it with all his energies.

In the mean time Mr. Hamlin again talked with Mr. Lincoln about the necessity of arming the negroes, and laid before him the letters he had received from his son and Appleton. He said to Mr. Hamlin, ‘I do not think that the people are yet up to it,’ and intimated that this was the chief obstacle. But an incident happened son after this decided President Lincoln that the time had come, and that Mr. Hamlin was right. About ten o’clock one night in January, 1863, Captain Cyrus Hamlin entered his father’s rooms at Washington in company with eight or ten officers of his acquaintance and of subordinate positions. Captain Hamlin had ascertained that they were willing to take command of colored troops, and had urged them to call with him on his father to ask him to use his influence with President Lincoln to that end. Mr. Hamlin was much impressed when he heard the object of his visitors’ call, and said that he and Secretary Stanton had long urged President Lincoln to take this step, but that they had failed to convince him that the time was ripe. He asked this question, ‘Would you, and other men like you, be willing to accept the same command in colored troops you now hold?’

‘Yes, sir, gladly,’ was the general reply.

This was proof enough to satisfy even the opponents of the negro soldier that the movement was patriotic and disinterested, and he replied: –

“Very well, if you are willing to undertake the task, I will see to it that you have an opportunity of presenting your views to the President,’ and he forthwith sent a messenger to Mr. Lincoln informing him that he would call at the White House the next morning at nine o’clock on important business. Mr. Lincoln answered that he would make the engagement, and with characteristic caution Mr. Hamlin enjoined on the officers the importance of presenting themselves to him ‘at a quarter to nine sharp.” He added: “Mr. Lincoln is a busy man, and we must not detain him a minute longer than necessary, nor keep him waiting at all.”

Mr. Lincoln met Mr. Hamlin and the officers at the appointed hour. Mr. Hamlin announced the object of the visit, and also said that the officers had volunteered to accept positions of equal rank among the colored troops. President Lincoln was both surprised and moved. He had no intimation of the nature of Mr. Hamlin’s visit, and undoubtedly he was touched when he heard the Vice President offer the services of his own son and those of other young officers in a cause that had aroused the strongest feelings of racial prejudice. His words show this. He first questioned Captain Hamlin and his comrades one by one to obtain their individual views, and then turning to Mr. Hamlin he asked: –

“What is your best judgment?”

Mr. Hamlin asked Mr. Lincoln whether he would not write the order at once. The President assented, and, sitting down at his desk, he rapidly penned an order to Secretary Stanton to form a brigade of colored men, to be officered by white men, and directing hm to remember the men Mr. Hamlin would introduce to him.

“May I be your messenger to Secretary Stanton?” eagerly asked Mr. Hamlin.

‘Yes, yes,” replied the President, smiling in his own quaint way, “take it to Stanton; take it to Stanton. I am glad to know that you are both satisfied.”

Without a moment’s delay the Vice President hurried to the War Department, found the secretary in his private room, introduced the officers, and told him the news.

“No, no, it can’t be possible!” exclaimed Stanton, with suppressed excitement, hardly daring to believe that one of his pet schemes was about to go into effect.”

“Here is the President’s order,” was Mr. Hamlin’s simple response. Hastily the secretary read it, was silent for a moment, and then, throwing aside his usual gruffness of manner, his real feeling came to the surface. Great tears welled up in his eyes and flowed over his careworn face. Then convulsively throwing his arms about Hamlin, he cried out with all the earnestness of a deep, strong nature, “Thank God for this! Thank God for this!”27

Hamlin biographer H. Draper Hunt, wrote: “The officers were willing to accept a rank in the new organization equivalent to the one each currently held, but Stanton would not hear of it. All were promoted in what became the Ullman Brigade.”28 It served under General Daniel Ullman.

Meanwhile , President Lincoln more actively explored the recruitment of black troops. In mid-January 1863, President Lincoln wrote General John A. Dix, who commanded the area adjacent to Fort Monroe in Virginia: “The proclamation has been issued. We were not succeeding – at best were progressing too slowly without it. Now that we have it, and bear all the disadvantages of it (as we do bear some in certain quarters), we must also take some benefit from it, if practicable. I therefore will thank you for your well-considered opinion whether Fort Monroe and Yorktown, one or both, could not, in whole or in part, be garrisoned by colored troops, leaving the white forces now necessary at those places to be employed elsewhere.”29 In his reply, Dix doubted if black soldiers could be recruited in the area controlled by his command:

I have just received Your “private and confidential” letter, and hasten to reply to it by the special messenger, who brought it

You do not ask my opinion in regard to the policy of Employing colored troops; and I infer that this is a question, which has been decided. I, therefore, answer only the special inquiry proposed to me: “whether Fortress Monroe and Yorktown, one or both, could not, in whole or in part, be garrisoned by colored troops, leaving the white forces to be employed elsewhere”.

I regard this Fortress under any circumstances and especially in view of the civil war in progress, as second to no other in the Union. It is the key to the Chesapeake bay and the great navigable rivers, which empty into it, and together with Fort Wool is the only protection for Hampton Roads, which were pronounced by the Board of officers, who reported on the Military defences of the U. S. in 1840 to be “the only good roadstead of the Southern coast.” By an enlargement of the canals between connecting Norfolk with Albemarle Sound, it may be made the entrepot for an internal system of Military and commercial communication of the highest importance extending from New York to Newburn and Beaufort. Even now this internal channel is a most valuable one for intercourse between this Department and that of North Carolina. Without this fort it could not be controlled for an hour.

In a political point of view it is to be considered that the tranquillity, possibly the loyalty, of Maryland may depend on the possession of this Fortress by the United States, severed as that State is by the Chesapeake Bay.

Under the circumstances I think this post should be held by the best and most reliable troops the Country can furnish commanded by the most experienced and trust worthy officers. Nothing should be put at hazard as respects either.

The garrison necessary for Fort Monroe in time of war has uniformly, I believe, been estimated at 2450 men, and that of Fort Wool at 1160 – together 4610.– The estimate for both in peace was 550. When I took command here on the 2. June last I found in this Fort a garrison of 642 men and at Fort Wool 181 in all 823. To enable the engineers to go on with the work I have withdrawn the garrison from Fort Wool, and my aggregate force at Fort Monroe is 885, of which only 693 officers and men are fit for duty. I have kept the garrison thus reduced nearly to the peace standard that I might employ all my disposable force nearer to the enemy. Of the aggregate force (885) in the Fort 858 compose the 3rd Regt. N. Y. Vols. one of the best in service, whose term expires four months from today. It is my opinion that it should be replaced by another equally reliable Regiment, and that, in case of necessity, the garrison should be filled up to the war standard by the same description of troops.

The question of employing colored troops at Yorktown may be determined by a totally different class of considerations. The position is of little practical importance except as controlling the York River and enabling us to facilitate and cover Military movements on the Peninsula above Yorktown, Should it be thought advisable to resume them. After the withdrawal of the Army of the Potomac, it was decided to retain it with a view to a removal of active operations in that quarter, and also to avoid the moral effect of abandoning a place recently captured and familiar to the whole Country through its historic associations.

If it be decided to employ colored troops any where, I know no place where they could be used with less objection. The proper garrison is 4000 men. One half of that number at least should be white troops. –

In connexion with this Subject I trust You will not consider me as transcending the proper limits of an answer to Your inquiry when I say, that I doubt very much whether colored troops can be raised here. An officer from Mass. who has taken an interest in the question, interrogated the adult males of the colored population at Camp Hamilton and Newport News and found only five or six, who were willing to take up arms. The general reply was, that they were willing to work, but did not wish to fight.

I deem it not improper to say further, that the feeling towards the north among a considerable portion of the colored refugees is not a cordial one. They understand that we deny them in many of the free States the right of Suffrage, and that, Even in those, where political equality is theoretically established by law, social prejudices practically neutralize it. The distrust such a state of things is calculated to produce is not diminished by the unwillingness recently manifested in the North to receive the fugitives, who have escaped from the insurgent States since the commencement of the war, and have thrown themselves on our protection. It is a very grave question, therefore, independently of all other considerations, how far military positions, on the tenure of which the Success of our arms in maintaining upholding the authority of the government and maintaining the integrity of the Union depends, should be confided to any other class than the white population of the country. Prudence would, at least, dictate that the inferior element in the Military organization should be incorporated in very small proportion, and employed in Services of secondary importance-30

President Lincoln consulted white leaders in other areas under Union control as well about recruiting black soldiers. President Lincoln explained to Tennessee’s Military Governor Andrew Johnson: “I am told you have at least thought of raising a negro military force. In my opinion the country now needs no specific thing so much as some man of your ability, and position, to go to this work. When I speak of your position, I mean that of an eminent citizen of a slave-state, and himself a slave-holder. The colored population is the great available and yet unavailable of, force for restoring the Union. The bare sight of fifty thousand armed and drilled black soldiers upon the banks of the Mississippi, would end the rebellion at once. And who doubts that we can present that sight if we but take hold in earnest? If you have been thinking of it please do not dismiss the thought.”31

According to biographers Nicolay and Hay, “There is no record that Governor Johnson ever made any reply to this proposal of the President. The Governor was already rendering important public service, and he perhaps reasoned justly that the time had not arrived when he could undertake a leadership full of such difficulties, uncertainties, and risks; although later in the same year he took hold of the task in a more restricted and qualified way, and cordially gave his personal and executive assistance in organizing colored regiments.”32

At the end of March, President Lincoln wrote General Nathaniel Banks who commanded the military district in New Orleans wrote about the brigade Mr. Lincoln had launched in his January talks with Vice President Hamlin: “Hon. Daniel Ullmann, with a commission of a Brigadier General, and two or three hundred other gentlemen as officers, goes to your department and reports to you, for the purpose of raising a colored brigade. To now avail ourselves of this element of force is very important, if not indispensable. I therefore will thank you to help Gen. Ullman forward with his undertaking, as much, and as rapidly as you can; and also to carry the general object beyond his particular organization, if you find it practicable. The necissity [sic] of this is palpable if, as I understand, you are now unable to effect anything with your present force; and which force is soon to be greatly diminished by the expiration of terms of service, as well as by ordinary causes I shall be very glad if you will take hold of the matter in earnest. You will receive from the Department, a regular order upon this subject-“33

A more systematic effort to recruit black soldiers nationwide was also underway. On May 23, 1863 the War Department issued General Order 143 to establish a Bureau of Colored Troops and set standards for black recruitment. In Louisiana, efforts to organize an effective force of black soldiers continued under General Banks, who was pro-recruitment of black soldiers but opposed to the use of black officers. In August 1863, General Banks wrote President Lincoln:

From a private note to one of the Editors of the ‘Era‘, I learn that some interest was manifested by you concerning the organization of the Negro troops in this Department, and especially with reference to General [Daniel] Ullman’s1 Brigade. I have purposely avoided the publication of information respecting the organization of that class of soldiers. General Ullman has now Five Regiments nearly completed numbering about Twenty Three Hundred men or five hundred to each Regiment. I have twenty one Regiments nearly organized, three upon the basis of a thousand men each, and Eighteen of Five Hundred men making in all ten or twelve thousand men. There are also batteries of artillery, and companies of cavalry in process of organization. These embrace all the material for such Regiments that is within my command at the present time. It is necessary to possess ourselves of other portions of country within the control of the enemy to increase this strength.

When I first assumed command in this Department I found Three Regiments in existence. They were demoralized from various causes and engaged in controversy with white troops to such an extent that the White Officers of these Regiments, as well as the Colored men who were in commission believed that it was impracticable for them to continue in service. This difficulty was caused in a great degree by the character of the Officers in Command. They were unsuited for this duty and have been most of the time, and some are still in arrest upon charges of a discreditable character.

The reorganization of these three regiments by the appointment of white Officers, and the organization of two other regiments of Infantry and a Regiment of Engineers were among the first acts of my administration in this Department. They embraced all the material then within the control of the Government for Regiments of this class. On the opening of the Teche Country in April, a large acquisition of recruits was obtained. The whole of these were appropriated to the organization of General Ullman’s Brigade. The siege of Port Hudson has largely increased our material, and enabled us to complete the force that I have described. The Regiments recently organized are limited to the number of Five Hundred for the following reasons.

First, the speedy instruction and discipline of these troops makes it necessary that the officers should have the most complete control over them and this is obtained by the smaller number much more certainly and efficiently than it would with the maximum number of men allowed.

Second, the skeleton organizations of Five Hundred well disciplined men enable us to add to the number whenever recruits may offer and we have these Regiments constantly in hand to receive any that may present themselves within or from beyond our lines. It was the practice in the organization of the Conscripts of France when they were required for immediate service to limit the battalions to three or four hundred men instead of one Thousand which was the maximum number. There is certainly reason for such limitation and I am sure that it will be found to be the only successful method of organization under the present circumstances.

Should our armies get possession of Mobile, or of Texas these regiments can be filled without delay and we shall have a force in this Department of at least Twenty Five Thousand good men. It is impossible to raise Negro Regiments except we get possession of the Country where negroes are. This is a fact overlooked by many persons who are greatly interested in the success of these organizations. The Regiments raised thus far have been of great service in this Department. I think it may be said with truth that our victory at Port Hudson could not have been accomplished at the time it was but for their assistance.

The number recruited could not have been increased materially up to this time. The movements now contemplated will enable me to carry out my original plan. The Command of white troops is for the reason I have stated preliminary to the organization of Black troops. I hope my command may be enlarged by filling up the Regiments now in this Department with conscripts or volunteers. My cavalry is deficient and should be at once increased.

Fifty or a Hundred Officers for the Corps d’Afrique would be of the greatest service if they could be sent at once34

Northern politicians were anxious to expedite the recruitment of black soldiers – if for no other reason than to reduce the pressure to use conscription to fill military recruiting targets. Historian Joseph T. Glatthaar wrote: “Unfortunately, some based their approval on harshly prejudicial grounds. One rationale for the use of black troops was that they could perform better than whites in the Southern climate, which may of course have been the cause for freedmen who lived there but not for Northern blacks. Strangely enough, these men unwittingly relied on the same argument that slaveholders used to justify the enslavement of blacks in the United States. Another popular reason for black enlistment, even among their future commanders, was that they could serve as Confederate targets as well as whites could, and that each black casualty spared a white one.”35

Meanwhile, impatient with the pace of recruitment, pressure was brought on President Lincoln to expedite the organization of black army units. Lincoln biographers Nicolay and Hay wrote:”We have seen how General [John C.] Frémont had failed in two important military trusts confided to his judgement and care. Notwithstanding these failures the general retained the admiration and confidence of many influential politicians and considerable classes of citizens in the country who believed that his prestige and ability ought to be utilized…”36 In late May 1863, a group of prominent New Yorkers including former Senator Daniel S. Dickinson, New York Evening Post Editor William Cullen Bryant , New York Tribune Editor Horace Greeley and industrialist Peter Cooper petitioned President Lincoln: “We appear as a Committee appointed at a public meeting of citizens held in the City of New York on the third day of May, 1863 to take measures to secure the enlistment of Colored Volunteers. We have been very laborious in the discharge of our duties, taking every opportunity to inform ourselves as to the facts as they exist, not in imagination but in reality. The conclusion to which we have arrived as the result of our most extensive observation and best judgement are set forth in a brief memorial which we now beg to read:”

An extensive observation and inquiry among the colored population of the Free States, has convinced your memorialists of the patriotism and devotion of this portion of our fellow citizens and of their willingness to bear their full share of the burdens, dangers and privations of the war against the rebellion. They are willing to volunteer for the Service upon the requisite assurance that they will be placed under leaders in Sympathy with the movement. Indeed, such is their intense enthusiasm and patriotism, that if the assurance can be given them, that upon their enlistment they will be in active Service under the command of Major General John C. Fremont, your memorialists are confident that a force of at least 10.000 could be placed under enlistment within Sixty days, forming a Grand Army of Liberation, Swelling in numbers as they pass along, thus giving effectiveness to the Proclamation of January, 1863.

Pledges of enlistment, conditioned upon these assurances being given, have already been obtained to the number of 3.000 names

Your memorialists therefore, respectfully petition your Excellency to place John C. Fremont in a Suitable command, and accept the ten thousand troops offered as above, and that the necessary orders may be issued to Secure the organization and mustering of the troops into the Service of the United States; that a rendezvous be named and instructions given to the local military agents of the United States to furnish the materials and facilities required for these purposes.37

The New York City group took their petition to the White House on May 30 to emphasize the seriousness of their request. Apparently, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner was present. President Lincoln responded to Senator Sumner a few days later:

In relation to the matter spoken of Saturday morning, and this morning, to wit, the raising of colored troops in the North, with the understanding that they shall be commanded by Gen. Fremont, I have to say:

That while it is very objectionable, as a general rule, to have troops raised on any special terms, such as to serve only under a particular commander, or only at a particular place or places, yet I would forego the objection in this case, upon a fair prospect that a large force of this sort could thereby be the more rapidly raised[.]

That being raised, say to the number of ten thousand, I would very cheerfully send them to the field under Gen. Fremont, assigning him a Department, made or to be made, with such white force also as I might be able to put in.

That with the best wishes towards Gen. Fremont, I can not now give him a Department, because I have not spare troops to furnish a new Department; and I have not, as I think, justifiable ground to relieve the present commander of any old one-

In the raising of the colored troops, the same consents of Governors would have to be obtained as in case of white troops, and the government would make the same provision for them during organization, as for white troops-

It would not be a point with me whether Gen. Fremont should take charge of the organization, or take charge of the force only after the organization,

If you think fit to communicate this to Gen. Fremont you are at liberty to do so.38

The New York Herald reported the President’s dilemma regarding General Frémont: “In this the President found himself in the position of the English gentleman who had a rake for a son, whom he told to take a wife. When the hopeful replied, ‘Well, father, whose wife will I take?’ The President took a map, pointing to the colored past representing the sections of the rebel States largely people by colored people. He noted that bordering on Vicksburg in particular, remarking that he hoped for co-operation from the negroes in that section to take Vicksburg and hold it. He had urged upon many generals to take the work of raising an army of colored men; but he could not prevail on them, because they had stars on their shoulders. He further informed the committee that he believed Frémont to be the man to do this work and give it effect, on account of his peculiarities and those of the colored people. He assured them that he would do all in his power to forward the movement. Mr. Chase was present during the interview, but never spoke. Senator Sumner was also present, and stated that he believed the greatest name to be written in these times will be written by the hand of that man who organizes the colored people into an army for their own deliverance and the restoration of the Union.”39

About 10 days later, Frémont wrote Sumner: “I have delayed a few days my reply to your kind note, for which I beg you to accept the reason that I was occupied with replying to the ungrounded – shifting – insaisiable [insatiable] and land squatter argument of Gen. [Benjamin] Butler in support of his claim to be the ranking General in the U. S. Armies.

I had deferred it until the time allotted for an answer began to run out – having been busy about the Pacific Railroad. I was pressingly reminded of your note by a visit from the committee which had called upon Mr. Lincoln & to which he had promised this letter to you. I beg you will say to the President that this movement does not, in the remotest way originate with me. On the contrary when the Committee called upon me I declined positively to enter into it, or to consent to having my name mentioned to the President in connection with it. The reasons which I gave to the Committee were simply that I disapproved the project of raising and sending to the field, colored troops in scattered and weak detachments. That it would only result in disaster to the colored troops & would defeat effectually the expectations of the Govt. to mass them in a solid force against the rebellion. No short reaching or partial plans can possibly succeed.

I told them that if I had been placed in the Dept. which the President & Secretary [sic] arranged for me when I was last in Washington & in which I should have had a suitable field for this organization and white troops to protect it – and ensure its success I could have undertaken it & have undoubtedly organized a formidable force imminently dangerous to the Confederacy. But these views were early [sic] in answer to the committee and ended my relation to the subject. I beg you to say to the President that I have no design to embarrass him with creating a Dept. for me. In my judgment this whole business is as dangerous and difficult as it is important. It demands ability and great discretion and a fixed belief in the necessity of the work and should only be undertaken upon some plan which would embrace the whole subject and then be intrusted only to some officer of ability and judgment to whom the President would be willing to give the necessary powers. He must have power and the President’s confidence. Therefore I do not propose my self for this work. But I make him the following suggestions it being understood that I am thrown out of the question – namely:

Make a Dept. of the Country west of the Mppi – Louisiana excluded – send them a suitable officer – give him full command of the Dept. & the white troops – [Missouri] Govr [Hamilton] Gamble himself included – & let him draw the colored troops togather [sic] from every quarter – and organize and consolidate them. He will have the whole line of the Mppi. river for his operations – and draw the Colored men from the free North & the freed men from the entire South. In this way the west country and the Mppi river would be closed to the Confederacy by an Army of 200000 men which at the proper time could take a deciding part in the war. This is my view of the subject, but is this time yet come? Will the President realize that if this summer’s campaigns are not successful the Confederacy is well nigh established? I think not. So if you think he will mix me up with the war plan makers of whose importunities he says he is tired – please say nothing to him about it. But pray don’t let him think that I am moving in any direction – or by any persons to get this command. Enclosed I return the President’s letter – which I have shewn to no one.

I informed the Committee that I had rec’d. it – through your self – but could not communicate its purport without the authority of the President.

Will you please make my thanks to the President for his friendly expressions in my favor and accept my very warm thanks to yourself. I have just had a visit from your Governor – interesting and agreeable as his visits always are[.]40

Historian John T. Hubbell argued: “For practical political reasons, Lincoln did not openly lead the movement toward the enlistment of blacks. Prior to 1863, long before he expressed enthusiasm for the idea, he allowed others to take the first steps; he remained silent, overruled them, or caused them to be overruled. He was always sensitive to political considerations and to the perquisites and powers of his office. Timing, the right moment, was critical – and Lincoln always deemed himself a better judge of the moment than those who advised him, formally or informally.”41

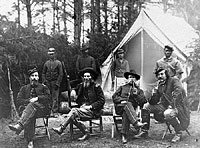

Lincoln biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay wrote: “To supply the steady, continuous official action necessary to broad success, the Government at length took up the work in its practical details. Early in April, 1863, the Secretary of War dispatched the adjutant-general of the army, General Lorenzo Thomas, to the West to examine and report upon the feasibility of recruiting and using negro soldiers; and his mission from the first was attended with success.” They noted that the recruiting by General Thomas, which was primarily done was limited by the Union operations underway in the spring of 1863 to capture the Confederate outpost on the Mississippi River at Vicksburg.42 Historian John T. Hubbell wrote: “Thomas was an effective recruiter, stressing that he spoke with the full authority of the president, the Secretary of War, and the General-in-Chief. Henry W. Halleck (who was notorious for his General Order No. 3 in 1861 had fallen in line with administration policy and now was telling other officers in the Mississippi Valley to do the same. Of particular interest was the reaction of Ulysses S. Grant, who early in the war had no more sympathy for emancipation than did many other regulars. Yet Grant was certainly a man to follow orders Washington. Indeed, he had already made provisions for organizing contrabands’ into a work force.”43

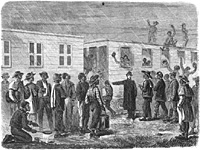

Black men and women were a vital part of the war effort, both in and out of uniform. By the end of the Civil War, one in 12 soldiers who served in the Union Army was black. About 10,000 blacks soldiers died in battle and three times as many died from illness. Historian Robert B. Edgerton wrote: “Their death rate was proportionately much higher than that of white soldiers in the Union Army, in part because they were so often used as assault troops and in part because their medical care was usually even worse than that given white troops.”44

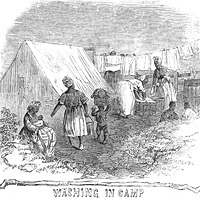

Edgerton wrote: “Many blacks would serve in USCT labor battalions, but before the war ended there would also be 120 black infantry regiments, 12 heavy artillery regiments, 10 companies of light artillery, 7 cavalry regiments, and 5 regiments of engineers. In all, by the war’s end, blacks made up 10 percent of the Unions forces.”45 Black men and some women served as nurses, scouts and spies. Men were employed as carpenters, cooks, laborers, teamsters, and surgeons – as well as in infantry and artillery companies. Historian Philip Shaw Paludan wrote: “While their service had not destroyed prejudice, it had helped destroy slavery in 39 major battles and 449 engagements, with 21 black Medal of Honor winners. Close to 119,000 former slaves had hammered off their own chains. The fighting by all the blacks had produced claims on white sympathy, linked them with an admirable cause, and laid the groundwork for changing some of the nation’s racial ideas.”46

Edwin S. Redkey wrote in A Grand Army of Black Men: “Most whites doubted that blacks would make good soldiers. They reasoned that blacks could not be relied on to fight their ‘superiors,’ the white troops of the Confederacy. This belief was put to rest in the spring and summer of 1863, however, when African-American troops began to prove their skill and courage in battle. Black regiments fought and died bravely on May 27 at Port Hudson, Louisiana, a rebel fortress in the swamps near the Mississippi River. A few days later Confederates tried to overwhelm a Union base where black troops were being trained at Milliken’s Bend, Louisiana. In hand-to-hand combat those fresh recruits drove off their attackers and won the praise of generals and the press. In July a black regiment helped rout Confederate troops at Honey Springs in the Indian Territory. The next day, July 18, 1863, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry led the bold but futile assault on Fort Wagner, near Charleston, South Carolina. Other major battles in which colored troops acquitted themselves well included the first attack on Petersburg, Virginia, on June 15, 1864, and the engagement at Nashville, Tennessee, on December 14-15, 1864.”47

Lincoln biographers Nicolay and Hay wrote: “If a single argument were needed to point out President Lincoln’s great practical wisdom in the management of this difficult question, that argument is found in the mere summing up of its tangible military results. At the beginning of December, 1863, less than a year after the President first proclaimed the policy, he was able to announce in his annual message that about 50,000 late slaves were then actually bearing arms in the ranks of the Union forces. A report made by the Secretary of War on April 2, 1864, shows that the numbers of negro troops then mustered into the service of the United States as soldiers had increased to 71,976. And we learned further, from the report of the Provost Marshal General that at the close of the war there were in the service of the United States, of colored troops, 120 regiments of infantry, 12 regiments of heavy artillery, 10 companies of light artillery, and 7 regiments of cavalry; making a grand aggregate of 123,156 men. This was the largest number in service at any one time, but it does not represent all of them. The entire number of commissioned and enlisted in this branch of the service during the war, or more properly speaking, during the last two years of the war, was 186,017 men.”48

Black recruitment changed the nature of the war for blacks and whites, for both northerners and southerners. James McPherson noted: “Emancipation and the enlistment of slaves as soldiers tremendously increased the stakes in this war, for the South as well as for the North. Southerners vowed to fight ‘to the last ditch’ before yielding to a Yankee nation that could commit such execrable deeds. Gone was any hope of an armistice or a negotiated peace so long as the Lincoln administration was in power; the alternatives were reduced starkly to Southern independence on the one hand or the unconditional surrender of the South on the other.”49

President Lincoln had to deal with a variety of problems with Northern and Border State politicians who objected to the recruitment of black soldiers. In September 1863, former Maryland Congressman John W. Crisfield, who had served with Mr. Lincoln in Congress in the 1840s, wrote to complain about the possible deployment of black soldiers in Maryland:

On my return home last night from an abscence [sic] of several days, I found this community agitated by a rumor that a force of black troops was soon to be sent here. I do not know how this rumor became current, or whether it reposes on any just foundation. I trust it is wholly untrue.

In a community like this, the advent of troops of that complexion, will necessarily stir up deep feeling, and no one can tell to what result it may lead. It will be difficult, if not impossible, to restrain all from the expression of the disgust, which some at least unhappily feel; and that expression will provoke retorts, which may produce serious consequences.

Our people are peaceful and quiet; they wish well to the government; and cheerfully submit to all its requisitions, and so will continue, unless they are exasperated by unwise and imprudent measures. Even the practice of running the blockade, which was never indulged in to aid the rebellion, but only from personal cupidity, has, as I have strong grounds for believing, wholly ceased. There is really no necessity here for troops of any sort, unless it be to catch deserters; and the few who are here are sufficient for that purpose. But if more troops are deemed necessary, I implore you not to send the blacks. Their presence violates the prejudices of this community, and every feeling essential to good order.

Our People, of course I speak of the majority, are entirely loyal to the Government, and among the most loyal, are the slaveholders. They have done and suffered much, and are ready to do and suffer all, that may be essential, for the suppression of the rebellion, and the restoration of constitutional authority. If they do not happen to agree with you, in all you think necessary for these objects, it is only a difference of opinion as to the means, and not as to the end. They recognize you as the lawful head of the Government, and desire to sustain you, in the just exercise of all your constitutional functions, to the end that you may, according to the regular course of the Constitution, transmit that Government to your successor, with all its powers unimpaired, and its authority every where respected. They have demonstrated this resolution in every form in which a People can express its sentiments; and this, it seems to me, should entitle them to some consideration and forbearance – If the presence of these troops were essential to the great cause of the Union, they would submit without a murmer; but it is not essential, And no fair minded man can say so; and it does seem to me, the sending of them here, under existing circumstances, would be a wanton an unnecessary, if not a wanton, strain on their constancy and endurance. I pray you to forbear; and, if such a measure is now, or ever has been, contemplated, which I cannot bring myself to believe, that the order may be witheld or countermanded.

Allow me also to bring to your notice the admirable letter of Gov [Augustus W.] Bradford on Negro enlistments, which has fallen under my eye since I began to write. The general sentiments of that letter are the sentiments of the Loyal People of Maryland, and I cannot too earnestly press them on your attention.

Mr President you have known me too long and too well not to feel assured, both of my loyalty and sincerity. I think you have no doubt on either point. Then let me assure you, in all truth and solemnity, that many of those in this State, who claim to be your peculiar friends, in this state, and boast of the favor with which their counsels are listened to, are not the best informed, or the safest advisers, of what is best for the advancement of the cause of the Union, and the restoration of national tranquility, so far, at least as this state is concerned. In their impetuous zeal for one object, they are oblivious of all others and unless restrained will plunge the state and you, into terrible difficulties wholly unnecessary, and which calmer judgements might easily avoid. I should be wanting in duty to you, to the country, and the peace and good order of my State, if I failed to convey to you this intimation.50

Kentucky Governor Thomas E. Bramlette was more worried about recruitment than deployment. He wrote President Lincoln in mid-October 1863: “Published dispatches from Washington, in this morning’s papers announced that in a few days orders will be issued from the War Dept for enlistment of negro soldiers in Ky, and other named States. Believing that I can offer controlling reasons of law and policy against such action in Ky, I respectfully but earnestly request, if such purpose be under consideration that I may be notified thereof and all action suspended as to Ky, until I can be heard. The dire effects of such a movement upon the interests of my people is my only apology for troubling you upon the authority of an irresponsible telegram.”51

At the same time, in Maryland, residents were increasingly upset by the use of black soldiers and recruitment of black slaves in the state. Their representatives visited Washington and were told by President Lincoln “that if the recruiting squads did not conduct themselves properly, their places should be supplied by others, but that the orders under which the enlistments were being made could not be revoked, since the country needed ablebodied soldiers, and was not squeamish as to their complexion.”52 General Robert C. Schenck wrote to President Lincoln to explain his actions:

The delegation from St. Mary’s County have grossly misrepresented matters. Col. [William] Birney went, under my orders to look for the site of a camp of instruction for and rendesvous [sic]for colored troops – See his report, this day forwarded to the Adjutant General-

He took with him, a recruiting squad, who were stationed, each with an officer at Mill Stone, Spencers, Saint Leonards, Dukes, Forest Grove & Benedict landings on the Patuxent– They are under special instructions, good discipline and have harmed no one-

The only disorder or violence has been that two secessionists, named Southeron have killed second Lieut. [Eben] White at Benedict, but we hope to arrest the murderers– The officer was a white man The only danger of confusion must be from the citizens, not the soldiers – but Col. Birney himself visited all the landings, talked with the citizens, and the only apprehension they expressed was that their slaves might leave them. It is a neighborhood of rabid secessionists. I beg that the President will not intervene and thus embolden them-53

Presidential aide John Hay recorded in his diary in October 1863 that “Schenck is complicating the canvass with an embarrassing element, that of forcible negro enlistments. The President is in favor of the voluntary enlistment of negroes with the consent of their masters & on payment of the price. But Schenck’s favorite way (or rather Birney’s whom Schenck approves) is to take a squad of soldiers into a neighborhood, & carry off into the army all the ablebodied darkies they can find without asking master or slave to consent. Hence results like the case of White & Sothoron. ‘The fact is,’ the President observes, ‘Schenck is wider across the head in the region of the ears, & loves fight for its own sake, better than I do.'”54

The next day, General Schenck and Piatt came to the White house to report on recruiting black soldiers in Maryland and the murder by John H. Sothoron of a Union recruiter, Lieutenant Eben White. Hay wrote in his diary: “Schenck & Piatt came in. Piatt defends flatly the forcible enlistment of negroes. Says it will be a most popular measure among the people of Maryland, & unpopular only among the slaveholders & rebel sympathizers. He says this man Sothoron is a recruiting agent for the rebels & that he would have been in the jug if they had got him as they expected before the murder.'”55 According to historian Michael Burlingame, “A former member of the Maryland legislature, Sothoron was about to be arrested for recruiting Maryland citizens into the Confederate army. He and his son escaped to Richmond and avoided all prosecution.”56 Donn Piatt, an erstwhile Ohio journalist who was an aide to Schenck, described in his memoirs what had transcribed and how he and Schenck had managed to annoy Mr. Lincoln. Piatt wrote of President Lincoln:

I never saw him angry but once, and I had no wish to see a second exhibition of his wrath. We were in command of what was called the Middle Department, with headquarters at Baltimore. General Schenck, with the intense loyalty which distinguished that eminent soldier, shifted the military sympathy from the aristocracy of Maryland to the Union men, and made the eloquent Henry Winter Davis and the well-known jurist Judge Bond our associates and advisers. These gentlemen could not understand why, having such entire command of Maryland, the Government did not make it a free State, and so, taking the property from the disloyal, render them weak and harmless, and bring the border of free States to the capital of the Union. The fortifications about Baltimore, used heretofore to threaten that city, now under the influence of Davis, Bond, Wallace, and others, had their guns turned outward for the protection of the place, and it seemed only necessary to inspire the negroes with faith in us as liberators to perfect the work. The first intimation I received that this policy of freeing Maryland was distasteful to the Administration came from Secretary Stanton. I had told him what we thought, and what we hoped to accomplish. I noticed an amused expression on the face of the War Secretary, and when I ended, he said dryly:

“You and Schenck had better attend to your own business.”

I asked him what he meant by “our business.” He said, “Obeying orders, that’s all.”