Postmaster General Montgomery Blair was the most conservative member of the Lincoln Cabinet on racial issues. Journalist Edward Dicey wrote for his English audience in 1861: “Beside the Abolitionists and the Democrats, there was a third party of the more moderate Republicans, whose chief representative was Mr. [William H.] Seward, and who were disposed to look very jealously on any proposition to interfere with the domestic institutions of the seceding states. Just at this time a great emancipation meeting was held at New York at which Mr. Montgomery Blair was invited to attend. This gentleman, the Postmaster General in Mr. Lincoln’s Administration, is a Maryland man. By one of the political combinations so universal in American politics, he had been selected by the Republican party to fill this post on Mr. Lincoln’s accession, not because he held anti-slavery views himself, but because it was believed that, out of personal connections, he would support Mr. [Salmon] Chase, who did. The result, however, proved that on all questions connected with slavery he sympathized far more strongly with Mr. Seward than with the Abolitionist portion of the Cabinet. His dereliction of strict anti-slavery principles had long been surmised; and in his letter declining to attend the above-mentioned meeting, he stated very distinctly the grounds on which he differed from his more Republican colleagues. It was in the following words that he expounded his views:

No one who knows my political career will suspect that I am influenced by an indisposition to put an end to slavery. I have left no opportunity unimproved to strike at it, and have never been restrained from doing so by personal consideration; but I have never believed that the abolition of slavery, or any other great reform, could, or ought to be effected by except by lawful and constitutional modes. The people have never sanctioned, and never will sanction, any other; and the friends of a cause should especially avoid all questionable grounds, when, as in the present instance, nothing else can long postpone their success.1

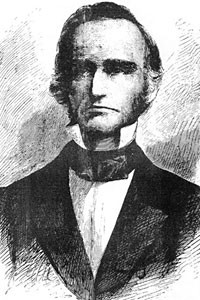

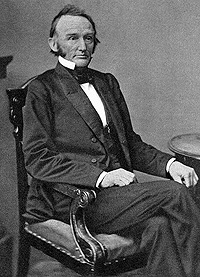

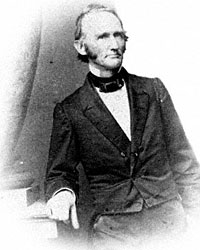

Historian Richard Nelson Current wrote: “Montgomery Blair, a tall, lean, hatchet-faced man with small and deep-set eyes, always spoke of secessionists deliberately but defiantly, though the family had many secessionist relatives. In his cold animus there was not a trace of the abolitionist spirit. True, he had won the respect of some abolitionists by serving as counsel for the slave Dred Scott, but he was no Negro-phile. His racist convictions were as strong as his Unionists convictions, and these were strong indeed.”2

Blair, according to fellow Lincoln Administration Charles A. Dana, was “was a capable man, sharp, keen, perhaps a little cranky, and not friendly with everybody, but I always found him pleasant to deal with, and I saw a great deal of him. He and Mr. [Edwin M.] Stanton were not very good friends, and when he wanted anything in the War Department he was more likely to come to an old friend like me than go to the Secretary. Stanton, too, rather preferred that.”3

Blair’s family connections sometimes worked against him rather than for him. To dislike one member of the Blair family was generally to dislike them all. Lincoln chronicler John Waugh wrote that “Frank’s temper was unsettling to the family. ‘Our only real trouble, [sister] Elizabeth confessed, ‘is Frank will give vent to some of his wrath which will only hurt himself & help his foes.’ And when that invariably happened, she would fret and write, ‘I confess to some nervousness about the outrageous insult F gave his colleague.’ Bad temper, this gentle sister thought, is ‘so unprofitable,’ anger ‘the poorest of counsellors.'”4

Montgomery Blair had policy and personalty conflicts with virtually all his fellow Cabinet members. Historian John Niven, biographer of Gideon Welles, wrote: “Blair’s dislike for Stanton bordered on hatred; his contempt for Chase ran dark and deep. Egotistical, voluble, and indiscreet, he broadcast his opinions of both men in conservative Republican and Democratic circles….As much as Welles liked Blair, he deplored his vindictiveness, his habit of judging everything and everything and everyone from a narrowly partisan perspective.”5

Blair family biographer William Earnest Smith wrote: “The Blairs believed their program for emancipation agreed with that of the President. In 1861 while the Blairs were powerful at the Executive Mansion, Montgomery Blair, after deep reflection, drew up a written statement of his views and advice on the subject for the President. There is a copy of this letter in the Blair Papers, bearing the date of November 21, 1861, in which he advises the President to recommend compensation for the slaves which were the property of Union men and had been lost through the operations of the war. He proposed the confiscation of the estates of traitors and the use of their property in payment for the freed negroes. ‘This deserves consideration,’ he says, ‘in view of the not improbable necessity of emancipation by martial law in the Gulph States.’ Such a blow, he thought, ‘would probably divide the slave holders & might bring openly to the side of the Union the greater portion of them…’ He believed, too, that the slaveholders would not accept the offer unless the President offered to provide for the colonization of the freedmen.”6

Chase biographer Frederick Blue wrote: “Brothers Frank and Montgomery had not only opposed Chase’s philosophies and ambitions but they were also at odds with him over patronage. Each felt it his right to control appointments in his state; Chase instead had rewarded Treasury patronage to their Republican factions, led by Henry Winter Davis in Maryland and B. Gratz Brown and Charles D. Drake in Missouri. Feelings were especially intense in Maryland when Chase refused to appoint a Blair man to a Treasury job in Baltimore and removed another pro-Blair appointee as collector of internal revenue in favor of a Chase favorite. During the 1863 political campaign in Missouri, Frank accused Chase of creating a corrupt political machine and of using his patronage against Lincoln. In a Saint Louis address, he referred to Chase as ‘no whit better than Jefferson Davis,’ a speech which led Chase to suggest to Lincoln that ‘General Blair’s unprovoked attack on me will injure its author more than its object.’ Thus, the Blair family was more than eager to pursue its attack on Chase when the Pomeroy Circular increased his vulnerability.”7

Montgomery’s position was further complicated by the outspoken nature of other family members. In the summer of 1861, Frank Blair clashed with John C. Frémont – about the time when brother Montgomery had been dispatched to Missouri to investigate Frémont’s leadership and when Frémont was exciting emotions with a proclamation on August 30 emancipating slaves in Missouri. Blair wrote President Lincoln on September 4:

I earnestly am pained to have to request that Genl Fremont may be superceeded in the command of the Western Department. The war men of St Louis concur in representing the condition of affairs there to be such that I am constrained against my own prepossessions to unite with them in the conclusion that this step is required by public interests.

I need not say to you that I have been reluctant to come to this conclusion. I am & have been for many years warmly attached to Genl Fremont & deeply regret the necessity of subjecting him to any mortification & would avoid if possible for myself the acknowledgment that he has not met the occasion as I was confident he would do when I urged his appointment

But being now satisfied of my mistake duty requires that I should frankly ack admit it and ask that it may be promptly corrected-

It is proper to add that the late proclamation of Genl Fremont has had no share in producing this request for that paper meets my approval & that the approval of I believe it is approved by the Union men of Missouri generally I believe generally of his Department[.] It is the inefficiency of his advisors so far as I have been able to generally But the dissatisfaction with little the paper has attracted little attention which attracts so much attention elsewhere proclamation seems to scar little scarcely be thought of by them & excites but but [sic] little comment-8

Montgomery wrote back to President Lincoln on September14: “I arrived here Thursday Evg & have had a full & plain talk with Fremont. He Seems Stupified & almost unconscious, & is doing absolutely nothing. I find but one opinion prevailing among the Union men of the State (many of whom are here) & among the officers, & that is that Fremont is unequal to the task of organizing the defences of the State.” The Postmaster-General went on to defend his brother:

Frank has endeavored to aid Fremont in good faith & has I believe the general confidence of the Union men of the State, but finding himself of no use has gradually withdrawn ceased to give counsel & limited himself to his immediate command. But Finding that this Fremont has commenced a warfare upon him in the newspapers It is probable indeed that the same jealousy which the special confederates of of Fremont openly manifested towards Lyon was felt towards Frank who was very much identified with Lyon in the popular mind and there is manifestly a purpose to take Franks regiment from him. An effort was first made to [vent?] Fremonts body Guard out of it Frank protested of course– That was relinquished only to start a scheme of taking away three of his German companies on the pretext of organizing them with other German companies Frank again protested This is the ground of attack in the newspapers in which it is said that Mr Politician Blair is no longer omnipotent in Missouri– That he has no commission as Col &c &c.

The whole thing betrays what my father said his proclamation showed, that his mind is heavy with petty aspirations & of course he is a prey to the petty jealousies incident to such a condition. I have telegraphed you to day that I think Gnl Meigs should be immediately put in command here. He is I believe the only man capable of the rapid organization which will put down the formidable power of the rebels in this state & put things here in a condition to turn the energies of the Govt upon the Head Quarters of Treason in the Gulph States when the hour comes for such operations. With the condition of things I find here continued, as I believe they are likely to be under Fremonts command we will be kept on the defensive & not be able to do any thing towards suppressing the insurrection from this quarter. No time is to be lost, & no mans feelings should be consulted. The people will sustain the right.9

Congressman Frank Blair showed his continuing ability to annoy radicals two and a half years later, when on February 27, 1864, he delivered a speech entitled ‘The Jacobins of Missouri.’ It was, according to Salmon Chase biographer Frederick J. Blue, “delivered without the president’s prior knowledge, [and] charged that as a result of corrupt Treasury practices, the Mississippi Valley was ‘rank and fetid with the frauds and corruptions of its agents’ and that permits to buy cotton were ‘just as much a marketable commodity as the cotton itself.’ Postmaster General Blair accelerated the distribution of his brother’s speech throughout the country and even accused Chase of having written the Pomeroy Circular.”10

Such skirmishes were par of an ongoing battle. The Blairs fought their adversaries at both national and state levels – Frank Blair in Missouri and Montgomery Blair in Maryland. Montgomery was at war with the more radical branch of the Republican Party in Maryland led by Henry Winter Davis. After his expulsion from the Cabinet in September 1864, Montgomery first sought to be appointed to the Supreme Court and failing that in February 1865, he sought to be elected to the Senate to replace Senator Thomas H. Hicks, who had died. Blair’s feud with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton came home to roost when the patronage appointees of the War Department rallied behind the radical candidate, Congressman John A. J. Creswell. The Baltimore Clipper, which backed Blair, reported: “The purse and the sword, the Treasury of the Untied States and all the patronage of the War Department may elect him [Creswell]….No persons ever wished him to be a candidate but Henry Winter Davis and his friends.”11

In addition to Chase, Montgomery feuded with Secretary of War Edwin Stanton. William Ernest Smith wrote: “Although the Blairs favored many of the war Democrats in political appointments, they could not bring themselves to accept Stanton at any time. Stanton, it appears, during the course of a conversation which he had in John Lee’s house in the early part of the war, set forth the advantages that would follow a division of the Union. Such talk was nothing less than treason. Montgomery Blair contended that Stanton talked secession to one class and loyalty to the Republicans. The Blair family never for a moment doubted the unreliability and selfish treachery of Stanton.”12

Blair was strongly pro-Lincoln and strongly anti-Radical. In October 1863, Montgomery Blair threw a grenade at the Radicals that landed in the middle of the Lincoln Administration. Lincoln chronicler John Waugh wrote: “It was a funeral Montgomery Blair had in mind when he went to Rockville, Maryland, in early October to address a Union Party meeting. The intended corpse was Sumner’s congressional-supremacy thesis. Just when it appeared peace was nearly won, the rebellion destroyed, and slavery suppressed, Blair began, ‘we are menaced by the ambition of the ultra-Abolitionists, which is equally despotic in its tendencies and which, if successful could not fail to be alike fatal to Republican institutions.”13 He linked Radical Republicans with racial amalgamation.

Blair family biographer William Ernest Smith wrote that: “Montgomery Blair, feeling that the time was auspicious for a blow at the audacious Radicals, made what proved to be the most unpopular of his speeches when he spoke to his friends at Rockville, a little town in Maryland. They were holding an Unconditional Union meeting there on Saturday, October 3, 1863. The speaker attacked the ultra-abolitionists and Radicals whose policy he conceived to be entirely out of harmony with that of the President. [Attorney General Edward] Bates thought that Blair courted the President assiduously in 1863 in order to retain his good opinion while he appealed to the Democrats for their support. Montgomery Blair, he said, was looking for jobs for his family whether the country went Republican or Democrats in the elections. Bates was unjust to Blair, inasmuch as Blair was begging his friend through letters to keep the Republicans in power to guarantee the end of slavery, and was supporting the President at every turn while he was attempting to organize a Republican party in the border states.”14

While attacking secessionists and their northern sympathizers, Blair reserved his harshest invective for Republican Radicals. He maintained that loyal unionists were “menaced by the ambition of the ultra-Abolitionists, which is equally despotic in its tendencies, and which, if successful, could not fail to be alike fatal to republican institutions. The Slavocrats of the South would found an oligarchy – a sort of feudal power imposing its yoke over all who tilled the earth over which they reigned as masters. The Abolition party whilst pronouncing philippics against slavery, seek to make a caste of another color by amalgamating the black element with the free white labor of our land, and so to expand far beyond the present confines of slavery the evil which makes it obnoxious to republican statesmen. And now, when the strength of the traitors who attempted to embody a power out of the interests of slavery to overthrow the Government is seen to fail, they would make the manumission of the slaves the means of in using their blood into our whole system by blending with it ‘amalgamation, equality, and fraternity.’“15

Blair’s speech created a storm of Radical outrage. After reading the report of Montgomery’s Rockville speech, Congressman Thaddeus Stevens wrote to Secretary Salmon P. Chase: “I have read with more sorrow than surprise the vile speech made by the P.M. Genl. It is much more infamous than any speech made by a Copperhead orator. I know of no rebel sympathizer who has charged such disgusting principles and designs on the republican party as this apostate. It has and will do us more harm at the election than all the efforts of the Opposition. If these are the principles of the Administration no earnest Anti-Slavery man will wish it to be sustained. If such men are to be retained in Mr. Lincoln’s Cabinet, it is time we were consulting about his successor.”16

Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “Beyond question the multifariously malicious Blair family was imperiling unity and Northern cohesion.”17 Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson wrote President Lincoln from Utica, New York at the end of October 1863: “We shall have some hard questions put at us in the next Congress. Blair is universally denounced for his speeches and actions and is every hour setting men against you. On the opening of Congress – when the pressure of the elections are over – the war he has made causelessly upon us will be repelled – at any cost.”18 Senator Zachariah Chandler wrote President Lincoln in mid-November to complain about conservative New York Republican Leader Thurlow Weed: “Will You pardon me for writing as Your Sincere Friend plainly and truthfully. The telegraph this morning says “Thurlow Weed Gov Morgan & Other distinguished Republicans are here, urging the President to take bold conservative in his Message” I have been upon the stump more than two months this fall & have certainly talked to more than 200.000 people in Illinois Ohio & New York and privately to many hundreds & have Yet to meet the first Republican or real War Democrat who stands by Thurlough [Thurlow] Weed or M Blair. All denounce them in most bitter terms.”19

California journalist Noah Brooks reported to his readers: “There is but one expression, and that of reprobation, toward Postmaster General Blair for his extraordinary course, and it now remains to be seen whether Lincoln will sacrifice his chances of a renomination by tacitly indorsing Blair’s ratiocinations by retaining him in the Cabinet. Although he was appointed to his place upon the urgent request of such radicals as Sumner and Wilson, against whom he now turns, we cannot expect that any sense of obligation to them would induce him to modify his own private views or restrain his public utterances. Good faith is not a characteristic trait of the Blair family. But good sense, at least, might have restrained him from loading his own wrong-headed opinions upon the Administration of which he is a member. Soon after the Pennsylvania election Judge [William D.] Kelley, of Philadelphia, and John W. Forney called upon the President with their congratulations – and Forney, with his usual outspoken candor, very plainly said to the President, Blair being then present, that his conservative friend Governor [Andrew G.] Curtin desired the President to know that if the Rockville speech of Postmaster General Blair had been made thirty days earlier it would have lost the Union ticket in Pennsylvania twenty thousand votes. He also expressed his astonishment to Blair that he, a Cabinet Minister, should have the hardihood to utter such sentiments in public, just on the eve of important elections in other States, as those of the Rockville speech. Blair responded that whatever Forney might think of the matter, he had only spoken at Rockville his honest sentiments. ‘Then,’ said the impetuous Forney, turning upon him, ‘why don’t you leave the Cabinet,’ and not load down with your individual and peculiar sentiments the Administration to which you belong?'” According to Brooks, “The President sat by, a silent spectator of this singular and unexpected scene….20

A few days later, presidential aide John Hay reported in his diary that “I handed the President Blair’s Rockville speech, telling him I had read it carefully, and saving a few intemperate and unwise personal expressions against leading Republicans which might better have been omitted, I saw nothing in the speech which could have given rise to such violent criticism.” The President replied: “The controversy between the two sets of men represented by Blair and by Sumner is one of mere form and little else. I do not think Mr. Blair would agree that the States in rebellion are to be permitted to come at once into the political family and renew their performances, which have already so bedeviled us, and I do not think Mr. Sumner would insist that when the loyal people of a State obtain supremacy in their councils and are ready to assume the direction of their own affairs they should be excluded I do not understand Mr. Blair to admit that Jefferson Davis may take his seat in Congress again as a representative of his people. I do not understand Mr. Sumner to assert that John Minor Botts may not. So far as I understand Mr. Sumner, he seems in favor of Congress taking from the Executive the power it at present exercises over insurrectionary districts and assuming it to itself; but when the vital question arises as to the right and privileges of the people of these States to govern themselves. I apprehend there will be little difference among loyal men. The question at once is presented, In whom is this power vested? And the practical matter for discussion is how to keep the rebellious population from overwhelming and outvoting the loyal minority.21

The next day, Hay reported that Philadelphia Congressman William Kelley came to the White House. “He came up with me talking in his effusive and intensely egotistic way about the canvass he had been making & speaking most bitterly of Blairs Rockville Speech. He went in and talked an hour with the President.”22

Nevertheless, Blair had his sympathizers and supporters. Connecticut Senator James Dixon wrote Blair: “I have seen a report of your recent speech, in the Herald, and am truly grateful to you for such words of truth & wisdom. Sumner’s heresies are doing immense harm in a variety of ways. If the position taken by him is understood to be the position of the Administration, thousands of our best men will cease to give it their support; and if his doctrines prevail the country will be ruined. I do hope most you & Mr Seward will stand firm– Mr Welles cannot differ from you unless he has changed the tenor of his life long opinions, which I do not believe. In the Senate I know you will find many supporters among the Republicans. It is impossible that the intelligence of that body should have sank to so low a point, as to permit the errors of the radicals to prevail there.”23

Historian William Ernest Smith wrote: The theory that Lincoln repudiated Blair because of the Rockville speech is not tenable. It is more logical to accept the opposite theory. Although he could not announce himself in favor of the Democrats in the border states, whom he distrusted, he realized that the Radical faction, which he distrusted as much as the Democrats, accepted only two phases of his policy: Freedom of the slaves, and the preservation of the Union. He was forced to choose some one whose views he accepted and in whom he could confide. Blair, who took his problems of consequence directly to the President, was the natural recipient of that confidence. Bates and Welles frequently observed his conversations with Lincoln in 1863. Frank Blair always thought that his brother talked with the President about all important matters concerning politics, the country, and the Blair family.”24

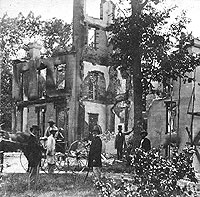

Despite his flaws and tempestuous nature, Montgomery Blair and his family were always loyal to President Lincoln – even when they had reason to think relationships had been seriously strained by events. Pressure on President Lincoln to dismiss Blair arose again at the Republican National Convention in Baltimore in June 1864. “After the convention adjourned, Blair submitted his resignation, which Lincoln rejected. Nevertheless, Blair gave Lincoln an undated letter of resignation, knowing that political pressures would probably force the president to accept it,” wrote historian William E. Gienapp.25 The next month, General Henry W. Halleck threatened to resign when the Postmaster General suggested that Halleck had been inept in defending Washington from the Confederate invasion led by General Jubal Early – and protecting the Blair family mansion from being burned. Halleck had written Stanton on July 13:

I deem it my duty to bring to your notice the following facts:

I am informed by an officer of rank and standing in the military service that the Hon. M. Blair, Post Master Genl, in speaking of the burning of his house in Maryland, this morning, said, in effect, that “the officers in command about Washington are poltroons; that there were not more than five hundred rebels on the Silver Spring road and we had a million of men in arms; that it was a disgrace; that General Wallace was in comparison with them far better as he would at least fight.”

As there have been for the last few days a large number of officers on duty in and about Washington who have devoted their time and energies night and day, and have periled their lives, in the support of the Government, it is due to them as well as to the War Department that it should be known whether such wholesale denouncement & accusation by a member of the cabinet receives the sanction and approbation of the President of the United States. If so, the names of the officers accused should be stricken from the rolls of the Army; if not, it is due to the honor of the accused that the slanderer should be dismissed from the cabinet.26

The President had to smooth over Halleck’s feelings and wrote Secretary of War Stanton: “The General’s letter, in substance demands of me that if I approve the remarks, I shall strike the names of those officers from the rolls; and that if I do not approve them, the Post-Master-General shall be dismissed from the Cabinet. Whether the remarks were really made I do not known; nor do I suppose such knowledge is necessary to a correct response. If they were made I do not approve them; and yet, under the circumstances, I would not dismiss a member of the Cabinet therefor. I do not consider what may have been hastily said in a moment of vexation at so severe a loss is sufficient ground for so grave a step. Besides this, truth is generally the best vindication against slander. I propose continuing to be myself the judge as to when a member of the Cabinet shall be dismissed.”27

Although President Lincoln did not yield to the pressure from General Halleck to dismiss Blair, he yield two months later to pressure from Michigan Senator Zachariah Chandler and other Radical Republicans to dismiss him. Chandler had tried to match the withdrawal of the independent presidential candidacy of General John C. Frémont with Blair’s expulsion from the Cabinet. Fremont had rejected a deal, but nevertheless withdrawn – sealing Blair’s fate.

Nevertheless, Blair’s loyalty to the President and ambition for another post remained undimmed. He unsuccessfully sought Mr. Lincoln’s nomination as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court later in the fall. On December 6, 1864, Blair wrote President Lincoln a long memo on his views on the progress of reconstruction.

In compliance with your request I commit to writing the views to which I referred in a recent conversation. The gradual suppression of the rebellion renders necessary now a persistence in the policy announced in your amnesty proclamation, with such additional provisions as experiment may have suggested – or its repudiation and the adoption of some other policy. For my part I recognize the plan already initiated by you as consonant with the constitution – as well calculated to accomplish the end proposed, and as tending to win over the affections of a portion of the disaffected citizens to unite with all the loyal to aid the work of the military power wielded by you – allying them in its consummation as the restorers of order and good feeling throughout the Union. This plan so far has had happy results. In Missouri – the Governor, Lieut[.] Governor, the Senate and House of Representatives, all concurring The State so far as its authorities were concerned was put out of the pale of the Union, and the State Militia assembled in front of its great city to assert the authority of the Rebel Confederacy. You have repeatedly driven out the rebel power and enabled the loyal people of the State to restore amend and reinvigorate their constitutional authority without the intervention of Congress – Kentucky paralized by the disaffection of the slaveholders and under the betrayal of its Governor, suppressed the loyal feeling of the masses by having the mask of neutrality imposed on it. The military force of the United States having expelled the armies from the South and their allies within the State, it has taken its true attitude on the basis of its own rights. Tennessee, Arkansas and Louisiana are on the point of embracing the amnesty proclamation and stepping into the Union under its provisions. They come recognizing the validity of your military proclamation – slavery being discarded wherever that reaches it, and so it is manifest, that just as soon as the regular military power of the Rebellion is driven out, the reign of the constitution of the Union is exhibited in the rising up of the State Government to resume its functions. The whole country hails in this auspicious beginning now assured of progress by your re election that your fundamental proclamation of freedom will be made universal by the vote of three fourths of the states extending and confirming it by constitutional amendment– No man of any party has the hardihood now to hint a doubt, that the scope of the measures so happily inaugurated, and proceeding under your auspices will secure forever the freedom of the slaves.

What then is the motive for annihilating State rights? It is certainly unnecessary to maintain Mr Sumner’s “doctrine of State suicide” “State forfeiture State abdication” – the doctrine “that the whole broad rebel region is tabula rasa, or a clean slate, where Congress under the Constitution may write laws” in order to secure the extirpation of Slavery. Yet Mr. Sumner in his paper on this subject seems to confine his purpose of reducing the States to territories to the object of bringing Slavery within the grasp of Congress. He argues, “Slavery is impossible within the exclusive jurisdiction of the National Government. For many years I have had this conviction and have constantly maintained it. I am glad to believe that it is implied in the Chicago platform. Mr. Chase, among our public men is known to accept it sincerely. Thus Slavery in the Territories is unconstitutional; but if the rebel Territory falls under the exclusive jurisdiction of the National Government then Slavery will be impossible there”– Slavery being no longer in question under the mode of deliverance you have adopted, why are the States to be disfranchised and denied their municipal right? There is a purpose, and one the accomplishment of which depends on Mr. Chase’s idea of disfranchising the states, turning them into territories, and giving to Congress the power of making their local laws. It is the purpose of depriving the States of their hitherto unquestioned right of regulating suffrage. The States have heretofore made laws denying the suffrage to citizens under age to females – negroes – Indians – aliens not naturalized and others incapacitated by moral or physical defects.

If the States resume their places in the Union under your proclamation and the loyal votes of the people are redeemed from the rebel usurpation, they may assert the political sovereignty as it stood of yore– This would enable the State Governments to exclude the classes from suffrage which from time immemorial the policy of free governments every where has for the most part retained in pupilage as well for the good of these feebler classes as the general good of the Commonwealth. The plan of denationalizing the States and throwing them out of the Union, because traitors have, for a time, enforced by arms an usurpation over them, the Government of the United States being unable in the emergency to fulfil its duty of protecting them, grows out of the ambition of another class of usurpers to seize the occasion of depriving the states of their indubitable municipal rights, while under the oppression of their secession enemies and unable to defend themselves in the councils of the Union– The object is undoubtedly to disfranchise the white race who created the state governments of the South, and who contributed their full share in asserting the national independence and creating the Government of the United States, and this is to be accomplished by the imposition of conditions by Congress on the admission of those states into the Union which necessarily forfeits those municipal rights heretofore exerted by all states in their internal Government. One object now avowed is, to enable Congress to constitute a government by exacting conditions on admission which shall put the blacks and whites on equality in the political control of a government created by the white race for themselves– This is not merely manumission from masters, but it may turn out that those who have been held in servitude may become themselves the masters of the Government created by another race. Mr. Chase, (whose friend Mr. Ashley first introduced into the House of Representatives the bill asserting power in Congress to make laws for the States – under the auspices of the then Secretary of the Treasury) succeeded through the management of Mr. Davis in carrying the measure. This revolutionary scheme looking to the establishment of a new control over the municipal rights of the State Governments in the South, has you well know been a favorite one, with the late Secretary. You will remember that Mr. Chase suggested the modification of your amnesty and reconstruction proclamation, so as to allow all loyal citizens to vote– This included all the freedmen while excluding all the whites who had been engaged in the Rebellion. This would probably have thrown the Governments of those states into the hands of the African race, as constituting the majority who had not borne arms against the Government, the whites generally, having forfeited the right of suffrage, and not likely to repent or to avail themselves of your amnesty, and the privilege of voting on Mr Chase’s terms. Mr. Chase had previously attempted to get you to recommend the establishment of provisional governments by Congress on the assumption that the States under usurpation, for want of protection on the part of the United States adequate to their defense, had committed suicide. These two schemes failing with you his next attempt to accomplish his object was through Congressional legislation. Failing in this through your refusal to sign the bill, his friends labored through the public press, and afterwards in the Convention to incorporate it in our party creed, and to make it an issue in the election, which would necessarily have defeated your nomination as its opponent. They not only failed on both these points, but Andrew Johnson was associated with you on the ticket – who had taken your stand on the question, and Tennessee was admitted as a State in the Convention as a practical comment to go to the country in condemnation of the doctrine of state suicide, which means that rebellion had triumphed in blotting out a state from the Union. Then the Davis manifesto was issued, and an intrigue set on foot to get up a new convention, and a new nomination, on the ground that you had put yourself in hostility to your party by refusing to resign the military power you as commander in chief had felt bound to exert in your proclamations of freedom of amnesty and reconstruction. Then to embarass [sic] you, Mr. Chase resigned in the fond hope that on his abandonment of the Treasury its stocks would fall and with them your credit in the country. He miscalculated his importance. On releiving [sic] the Treasury of his weight, the government securities rose rapidly. Your policy has stood the test of all these artfully prepared, ably conducted and most sinister attacks, and it has passed through the crucible of the late presidential election. It has the stamp of the popular sovereignty which alone has the right to decide authoritavely [sic], all fundamental contests among its political Departments or agencies.

Still Mr. Chase and his friends do not rest satisfied with this decision. The Davis Manifesto declares on the authority of the Supreme Court, that it rests with Congress to decide “what Government is the established one in a State” and cites a case arising out of the Dorr rebellion in Rhode Island, and based on the right of the two Houses of Congress to say what members of Congress from that State were its true representatives. In fact, however, the decision of the court did not turn on such a state of case. Judge Taney in his opinion distinctly asserts that it was the recognition of the Governor opposed to Dorr, by the President of the United States in the exertion of his military authority in his support, that established which of the two asserting the right of Governor, was the true one. Mr. Taney declines the decision of the question, saying “much of the argument on the part of the plaintiff turned upon political rights, and political questions upon which the court has been urged to express an opinion. We decline doing so,” and declaring why it would not “overstep the boundaries which limit its jurisdiction”, concludes its decision with this pregnant remark, “no one we believe has ever doubted the proposition, that according to the institutions of this country, the sovereignty in every state, resides in the people of the State, and that they may alter and change their form of Government at their own pleasure. But whether they have changed it or not by abolishing an old government and establishing a new one in its place is a question to be settled by the political power – and when that power has decided the courts are bound to take notice of its decision, and follow it.” Well, what was the political power which exerted itself against the Dorr rebellion in Rhode Island which the court felt bound to follow? It tells us in these words, “The militia were not called out by the President. But upon the application of the Governor under the charter government, the President recognized him as the executive power of the State, and took measures to call out the militia to support his authority if it should be found necessary for the general government to interfere; and it is admitted in the argument, that it was the knowledge of this decision that put an end to the armed opposition to the charter government, and prevented any further efforts to establish by force the proposed constitution. The interference of the President, therefore, by announcing his determination, was as effectual as if the militia had been assembled under his orders. And it should be equally authoritative. For certainly no court of the United States, with a knowledge of this decision would have been justified in recognizing the opposing party as the lawful government, or in treating as wrongdoers or insurgents the officers of the government which the President had recognized and was prepared to support by an armed force. In the case of foreign nations, the government acknowledged by the President, is always recognized in the courts of justice. And this principle has been applied by the act of Congress to the sovereign states of the Union.

“It is said that this power in the President is dangerous to liberty, and may be abused. All power may be abused if placed in unworthy hands. But it would be difficult, we think, to point out any other hands in which this power would be more safe, and at the same time equally effectual. When citizens of the same State are in arms against each other, and the constituted authorities unable to execute the laws, the interposition of the United States must be prompt, or it is of little value. The ordinary course of proceedings in courts of justice would be utterly unfit for the crisis. And the elevated office of the President, chosen as he is by the people of the United States, and the high responsibility he could not fail to feel when acting in a case of so much moment, appear to furnish as strong safeguards against a wilful abuse of power as human prudence and foresight could well provide. At all events, it is conferred upon him by the constitution and laws of the United States, and must therefore be respected and enforced in its judicial tribunals.” You have adopted the principle here recognized, in the much stronger case of the Southern rebellion which had put in abeyance the civil power both of the States and the United States by force of arms, in almost all of the slave states– Yet “the State Governments may be regarded (says Mr. Madison in the federalist) as constituent and essential parts of the federal government”. How then can Mr Sumner pronounce “that the States by their flagrant treason have forfeited their rights as States so as to be civilly dead.” while the federal government lives and its head, the President, recognizes their existence and his duty to maintain them “as constituent and essential parts of the federal government” which he is sworn to maintain? The State constitutions which their representatives brought in their hands when the united governments were formed became parts of the constitution of the United States, and these charters conveyed to the Nation the right of eminent domain in every acre of land in the several states and the common bond was the acknowledgment that the constitution of the United States and laws made in pursuance thereof, was the supreme law of the land– Now can it be admitted that suppression for limited time, of the civil power, state and national, in a part of these boundaries, by Rebellion, or invasion of a foreign foe, destroys either the superior or subordinate government within them. Messrs. Chase Sumner, Davis &c assert that the constitutions and the rights of the States under the Constitution of the United States are abolished by the rebellion You, on the contrary have asserted both the rights of the States and the rights of the United States by the constitutional exertion of the military power of the nation in all its plenitude to crush down the rebellion and uplift the suppressed civil power of the State and Federal government that they might resume their full constitutional vigor. As a necessary military measure to effect this result, you have abolished Slavery by proclamation, and as far as possible have withdrawn its strength from the enemy. The amnesty and re construction proclamations have the same view– These are the emanations of the war, accompanied by, and receiving their efficacy from the application of all the physical force, moral and mental energy of the nation which you as commander in chief are called upon by office to direct, to take the place of the civil power which has been dislodged in the section where the war prevails– You are compelled to act on the maxim “inter arma leges silent” that the voice of the nation speaking from the cannons mouth may become effective. In this state of things, the same men who insisted on your military proclamations as essential to the salvation of the country now insist that Congress must interpose to make provisional governments for states, as if they were not states and had no constitutions assuming that the Supreme Court recognize this mode of proceeding to supplant the power you have exerted as commander in chief, over the very scene of its military exhibition for the restoration of the civil power which the rebel armed power is attempting to hold in subjection. Your proclamation responding to the attempt of Congress to legislate on false assumptions of facts, and to take from you the command in chief when the Constitution places it absolutely in your hands – when all civil government is suspended in the presence of military government on either side – takes the true view of the question. Although you are unprepared “to declare a constitutional competency in Congress” to pass the act for the States in virtue of its power as superceeding their own, You are nevertheless “fully satisfied with the system of restoration contained in the Bill as one very proper plan for the loyal people of any state choosing to adopt it,” and you are prepared to give the executive aid and assistance to any such people as soon as the military resistance to the United States shall have been suppressed in any such State”– In this you do not resign “the Chief command” committed to you by the constitution until the military resistance requiring it is suppressed, nor regard the State Governments as extinct to be supplied with legislation by Congress, but always to choose “whether it they will adopt its legislation or not. This repudiates, as I understand it, the power of Congress to make governments for the States, or to compel them to submit to conditions as the price of their assuming their place in the Union. A fortiori, I conclude, that as you do not submit the military measures which as commander in chief, the constitution authorizes you alone to execute, to the legislation of Congress, you do not admit a right of jurisdiction over them as existing in any court, which would be an admission that they might be annulled or enjoined and so defeated by judicial authority– This is the ground taken by me in my Cleaveland [sic] speech last year[.] The Supreme Court in the passage I have quoted denies to itself the right of adjudicating on political questions which it says are to be referred to the sovereignty in which they originate, and much less can the courts intrude into military jurisdiction, and set aside measures of the commander in chief looking to the salvation of the Republic.

The course, therefore, which Mr. Chase and his followers have adopted has tended to counteract most of the leading measures to which you committed your own destiny, and that of the nation. His proposal to surrender Fort Sumpter and let the South “go in peace” rather than resist the Traitors – His long cherished doctrine of State suicide – State annihilation – by way of subjecting the returning States of the South, coming in under your proclamation, and with the sanction of the suffrages of their loyal citizens to the humiliation of receiving their law and constitution with conditions annexed, from a Congress of northern members without a representative of their own among them[.] The establishment of a precedent thus, which might be pushed to the establishment of that “equality before the law” now so strenuously urged in favor of the freedmen’s rights as to deprive the white people of their right of municipal legislation for the avowed purpose of introducing negro suffrage, in the South to counteract that of the white citizens in the South – a measure already broached by B. Gratz Brown in Missouri – The intrigue of Mr. Chase and his partizans to defeat your re nomination and subsequently to set it aside by the vote of another convention, are all parcel of the same subverting policy, which the Davis Manifesto invokes a decision of the Supreme Court to sanction. As no such opinion is to be found, Mr Chase presents himself to you for the appointment of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, where he doubtless would furnish one for the purpose if he did not discover that it might conflict with his higher aspirations.28

Footnotes

- Edward Dicey, Spectator in America, p. 84-85.

- Richard Nelson Current, Lincoln and the First Shot, p. 27.

- Charles A. Dana, Recollections of the Civil War, p. 157.

- John Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, p. 118.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p.471.

- William Ernest Smith, The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, p. 195-196.

- Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics, p. 227.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Montgomery Blair to Abraham Lincoln, September 4, 1861).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Montgomery Blair to Abraham Lincoln, September 14, 1861).

- Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics, p. 228.

- Harry. J. Carman and Reinhard H. Luthin, Lincoln and the Patronage, p. 324-325.

- William Ernest Smith, The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, p. 232-233.

- John Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, p. 65.

- William Ernest Smith, The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, p. 237-238.

- Leonel L. Richards, Who Freed the Slaves?: The Fight over the Thirteenth Amendment, p. 130.

- Ralph Korngold, Thaddeus Stevens: A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great, p. 219-220.

- Allan Nevins, War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865, p. 105.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Henry Wilson to Abraham Lincoln, October 25, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Zachariah Chandler to Abraham Lincoln, November 15, 1863).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 78 (October 30, 1863).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 105-106.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 107 (November 2, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from James Dixon to Montgomery Blair, October 7, 1863).

- William Ernest Smith, The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, p. 242-243.

- William E. Gienapp, Abraham Lincoln and Civil War America, p. 163.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Henry W. Halleck to Edwin M. Stanton, July 13, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 440 (Letter to Edwin M. Stanton, July 14. 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Montgomery Blair to Abraham Lincoln, December 6, 1864).