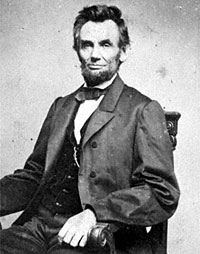

Secretary of War Simon Cameron became radicalized on the issue of emancipation during the fall of 1861. Perhaps he merely became political. Cameron accompanied Congressman John Cochrane on a New England speaking tour in which Cochrane advocated the military use of former slaves and Cameron endorsed that use. Historian Burton J. Hendrick wrote: “thus Lincoln’s own Secretary of War, in face of repeated admonitions, was openly defying the administration on the most delicate problem of the hour. The one way of saving his official head, as Cameron diagnosed the situation, was to make himself so acceptable to [Charles] Sumner, Ben Wade, [Zachariah] Chandler, and others – for the most part, the Chase following – that they would insist on his retention in the cabinet. In accordance with this strategy, Cameron, in the latter part of the year, played his final card.”1

Lincoln biographer Robert Morse wrote: “Secretary Cameron twice nearly placed the administration in an embarrassing position by taking very advanced ground upon the negro question. In October, 1861, he issued an order to General Sherman, then at Port Royal, authorizing him to employ negroes in any capacity which he might ‘deem most beneficial to the service.’ Mr. Lincoln prudently interlined the words: ‘This, however, not to mean a general arming of them for military service.’ A few weeks later, in the Report which the Secretary prepared to be sent with the President’s Message to Congress, he said: ‘As the labor and service of their slaves constitute the chief property of the rebels, they should share the common fate of war….It is as clearly a right of the government to arm slaves, when it becomes necessary, as it is to use gunpowder taken from the enemy. Whether it is expedient to do so is purely a military question.’”2

Cameron’s report advocating black troops split the Cabinet and Congress. Cameron biographer Edwin S. Bradley wrote: “During the progress of a dinner party given by John W. Forney, Cameron invited the select circle to pass judgment on the questionable part of his proposed report. His host warned: ‘It will never do, Mr. Secretary,’ and implored Cameron, ‘For God’s sake,’ not to insist upon inserting it. ‘Put it in sir!’ shouted [Pennsylvania Congressman] David Wilmot, ‘By God sir, it is right!’ When [Interior Secretary] Caleb Smith attacked Cameron for his view, Edwin M. Stanton stood silent; yet it was this controversial figure who penned for Cameron the most obnoxious phrases of the report.”3 New York Democrat Samuel L. M. Barlow heard of the quarrel and wrote: “I am glad to learn by the papers to-day that there has been a collision of sentiment between Cameron and Smith.”4

The Union Navy was already employing black seamen. Historian John Niven wrote: “When the secretary of War made an impassioned demand for arming fugitive slaves at a Cabinet meeting on November 15, Welles did mark Lincoln’s obvious displeasure. He had taken no part in the discussions, nor had Montgomery Blair, whom he knew opposed Cameron’s position. [William H.] Seward, usually so garrulous, was silent also, though Welles thought he spoke through his ‘creature,’ Caleb Smith, the Secretary of the Interior, who took Cameron to task, as did Edward Bates. Had Welles been asked, he would have supported Cameron, because the Navy was actually doing what was merely claimed for the Army.”5

Historian John Niven wrote: “This was a tense Secretary of the Navy who took his usual place on the sofa in the Cabinet room on Friday morning, November 29. When all were seated, Lincoln remarked that his own report was still unfinished, and then stated flatly that the War Department’s policy on fugitive slaves was contrary to administration policy. All references to this subject must be stricken before the report was made public. Though Lincoln’s peremptory demand may have nettled Cameron, it did not perturb him. If his comments on fugitive slaves had ventured on forbidden ground, which he denied, what of the Secretary of the Navy’s report? Cameron insisted that Welles’ position on that question was just as objectionable.”6

Historian Allan Nevins wrote of Cameron: “Unquestionably he was sincere in his repeated assertions that to strike at slavery was to strike at the root of insurrection. The theory that he was taking an abolitionist stand in order to gain Radical protection against dismissal is unjust. For one reason, he was aware by October that his fate was determined. ‘I knew I was doomed when I consented to go to St. Louis,’he shortly assured old F.P. Blair, ‘and was not altogether clear of suspicion that it was intended I should be by one of my associates [Seward], but having determined to shrink from no duty I went cheerfully, only taking care to let the President know my belief, and to get his promise that I should be allowed to go abroad when I left the Department.’ He knew Lincoln well enough to understand that no Radical intervention could help him. Moreover, this vigorous Jacksonian (now sixty-two, he was destined to live to ninety) had long detested slavery, and believed that blows at it would shorten the war. ‘I can safely say,’ he told Blair, ‘that I have not done an official act that I would not do again, under the same circumstances. But there are many things I would have done, which were omitted only because my associates were not as advanced as I was in hostility to the rebellion.”7

But, regardless of principles, in practice Cameron risked his job by not clearing his annual report to Congress with the nation’s Chief Executive. Journalist Ben Perley Poore wrote: “Simon Cameron’s report as Secretary of War, as originally prepared, printed, and sent over the country for publication, took advanced ground on the slavery question. He advocated the emancipation of the slaves in the rebel States, the conversion to the use of the National Government of all property, whether slave or otherwise, belonging to the rebels, and the resort to every military means of suppressing the Rebellion, even the employment of armed negroes.”8 Cameron turned in his report to the President on November 30 and put the report in the mail to press the following day. When Mr. Lincoln finally read the report, he summoned Cameron to the White House for a private confrontation, followed by a more public meeting with other Cabinet members. Although Cameron argued that his proposals were no more offensive than those of Secretary of the Navy Welles, the President was adamant that the report be changed.

The President’s position was not necessarily consistent, wrote Welles biographer John Niven. “By letting Welles’ report stand uncorrected he was signifying that his policy on fugitive slaves was a flexible one. The time had not yet come for the enlistment of black soldiers, but it had arrived for utilizing black sailors. The fact that the Navy was smaller and less conspicuous than the Army, that it occupied no territory, and that it was organized on national and not state lines made it an ideal means for the administration to present a radical face to the public. In another way too, the President was saying that the Seward-Weed influence had not gained the upper hand, that there was still a balance between radicals and conservatives in the Cabinet. The public still thought of Welles as a Chase man, a general impression not lost on the President. Welles’ few lines on fugitive slaves were meant to show the radicals of the North that Lincoln had not abandoned them.””9

Niven wrote that: “Welles was prepared to defend his actions even to the point of resignation. But, strangely enough, Lincoln brushed off Cameron’s allusion to the Navy, insisting that only the Army must conform. When Cameron told him that copies of his report were already in the hands of postmasters all over the country, the angry President directed Montgomery Blair to get in touch with them and have the reports returned. Blair did his best, and he tied up all the telegraph lines of the country for the next twenty-four hours. But some postmasters never got his message, so some of the unofficial versions got into the hands of the editors, who gleefully published them without official sanction.”10

Journalist Ben Perley Poore wrote: “President Lincoln, at the instance of Secretary Seward and General McClellan, declined to accept these anti-slavery views from his subordinate, and ordered the return of the advance copies distributed for revision and amendment. It happened, however, that several newspapers had published the report as originally written. When they republished it, as modified, the public had the benefit of both versions. The President struck out all that Secretary Cameron had written on the slavery question, and substituted a single paragraph which was self-evidently from the Presidential pen. The speculations of the Secretary as to the propriety of arming the negroes were canceled, and we were simply told that it would be impolitic for the escaped slaves of rebels to be returned again to be used against us. Secretary Chase sustained Secretary Cameron, but Secretary Seward, the former champion of higher law and abolitionism, was so conservative at this crisis of the great struggle between freedom and slavery, as to disgruntle many ardent supporters of the principles of which he had once assumed to be the champion.”11

Cameron had wanted to be Secretary of the Treasury, not Secretary of War. His management of the War Department had been highly criticized, with the publication of his controversial report, he suddenly became a hero to radicals. Ralph R. Fahrney, biographer of Horace Greeley, wrote: “Secretary Cameron was not accepted for the war portfolio with any marked degree of enthusiasm, but when he stepped out in the direction of emancipation, thenceforth the Tribune vigorously defended him against all critics, charitably overlooked alleged corruption as the work of ‘unprofitable friends,’ and praised the management of the War Department to the skies.”12

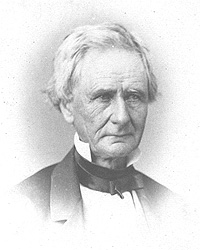

Such support did Cameron little good. Within six weeks of the publication of his report, Cameron had been replaced as Secretary of War. Ironically, Cameron’s successor in the War Office was to prove a strong but more pragmatic advocate of the use of black soldiers. Frank A. Flower, biographer of Edwin McMasters Stanton wrote:

Stanton’s call to the War Office was as sudden and unexpected as the summons to become attorney-general in Buchanan’s cabinet. The question arose on the 11th of January, and on Monday, the 13th, his nomination was sent to the Senate. Senator [Charles] Sumner, at the executive session later in the day, moved immediate confirmation ‘because,’ he said, ‘Mr. Stanton does not agree with those who want the war so managed as to save slavery no matter what else result, but believes that the war should be prosecuted to save the Union and that everything necessary should be made to contribute to its success.’ As there was objection, the motion was withdrawn and a committee of Republicans was raised to ‘investigate Stanton’s loyalty.’ The report came forthwith that he was ‘all right,’ and his confirmation and a commission from the President followed on the 15th.

Interesting, indeed, is the fact that Lincoln was unaware that the iron-willed giant he was putting in was more stubbornly in favor of enlisting and arming the slaves of rebellious masters than the man he was putting out. Lincoln was also unaware that the recommendation which, with his own hand, he had expunged from Cameron’s report and which was the means of forcing its supposed author out, was conceived and written by the very man now going in — but so it was; and so it may be said that Stanton wrote his own appointment!13

Footnotes

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 230

- Robert Morse, Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, pp. 8-9.

- Edwin S. Bradley, Simon Cameron, p. 203.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 48 (Letter from Samuel L. M. Barlow to Edwin M. Stanton, November 21, 1861).

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 392.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 395.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Improvised War, 1861-1862, pp. 398-399.

- Ben Perley Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences, Volume II, pp. 96-97.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 395.

- John Niven, Gideon Welles: Lincoln’s Secretary of the Navy, p. 395.

- Ben Perley Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences, Volume II, p. 97.

- Ralph R. Fahrney, Horace Greeley and the Tribune in the Civil War, p.121

- Frank A. Flower, Edwin McMasters Stanton, p. 117

Visit

Samuel L. M. Barlow(Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Francis P. Blair, Sr. (Mr. Lincoln’s Whitehouse)

Montgomery Blair

Simon Cameron (Mr. Lincoln’s Whitehouse)

Caleb Smith (Mr. Lincoln’s Whitehouse)

Gideon Welles (Mr. Lincoln’s Whitehouse)