“That Lincoln perceived the larger implications of the action now to be taken we cannot doubt. Some Radicals thought he was too deliberate in dealing doom to the institution, as some Democrats declared that he was an intemperate abolitionist,” said Allan Nevins. “Not only was he convinced that, even if emancipation had become ‘an indispensable necessity,’ events had not conferred upon him ‘an unrestricted right’ to act in accordance with his feelings; he felt a firm though still unformulated conviction that the North had entered upon a course of enlarging social and racial equality that would require cautious if courageous definition.”1

Contemporary journalist Noah Brooks wrote: “It should be recalled that the House on the previous occasion, when it failed to pass, June 15, 1864, gave the amendment 95 ayes to 66 noes, a two-thirds vote being necessary; and when the measure came up for final passage on January 31, [1865], anxiety and expectation sat on every countenance. But on the floor of the House, where the friends of liberty and freedom were circulating tallylists which they had prepared for their own private information, there was a general air of cheerfulness and confidence. The galleries, corridors, and lobbies were crowded to the doors, and the reporters’ gallery was invaded by a mob of well-dressed women, who for a time usurped the place of the newspaper men; and these, considering the importance of the proceedings and the gravity of the impending event, surrendered their seats with good grace. On the floor of the House were Chief Justice Chase and the Associate Justices [Noah H.] Swayne, Miller, Nelson, and Field, Secretary [William Pitt] Fessenden, Postmaster-General [William] Dennison, senators by the dozen, the electoral messengers from Oregon, Nevada, and California, ex-Postmaster-General Montgomery Blair, and hosts of other prominent persons.”2

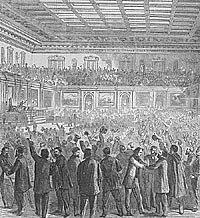

Expectations ran high. “Agreement had been reached that debate should close on January 31, at three o’clock in the afternoon, when the roll was to be called. From early morning of the appointed day the public gallery was crowded. As the hour approached the reserved gallery filled. Senators, cabinet ministers, and spectators mingled with representatives on the floor. Outside a crowd had gathered. In newspaper offices throughout the North presses waited for the click of the telegraph instruments.” historian Ralph Korngold wrote. “There was a hitch in the proceedings. Ashley, in charge of the resolution, had allowed himself to be persuaded to extend the time of debate. The extension was short, but men were too wrought up to view the matter calmly. An angry crowd gathered around the congressman from Ohio. Conspicuous among them was the bewigged Commoner, who with wagging finger read Ashley a lecture. ‘Stevens’ face looked fire, while Ashley’s was as red as a fresh cut of beet,’ the New York Herald reported.”3According to historian Earl Schenck Miers,”Harper’s Weekly devoted two pages to a pen-an-ink sketch of that memorable scene. Ladies in fine dresses occupied the boxes around the main floor, and many held seats usually reserved for the press. No desk was unattended, no aisle unfilled. Whiskers and bowler hats dominated the sketch.”4

According to historian Allan Nevins, “The direction of the wind was indicated when applause greeted the Democrats, James English of Connecticut, and John Ganson of New York as they voted ‘aye.’ The four Democrats who had previously voted in favor did so again, to be joined now by thirteen others. In addition, eight Democrats were reported absent without pairs, a result which Lincoln’s secretaries admit was ‘perhaps not altogether by accident.'”5Contemporary journalist Noah Brooks wrote:

When the hour for taking the vote approached, Archibald McAllister, a Pennsylvania Peace Democrat, astonished everybody by sending up to the clerk’s desk a note in which he said that as all peace negotiations and missions had failed, he was satisfied that nothing short of their independence would satisfy the Southern Confederates, and he therefore determined to cast his vote against the corner-stone of the Southern Confederacy – slavery. Several other Democrats and Border State men, who had heretofore withheld their support of the constitutional amendment, also came in with brief explanations of the vote which they now proposed to cast in the affirmative. The supreme moment finally arrived, Speaker [Schuyler] Colfax’s ringing voice demanded of the House ‘Shall the Joint Resolution pass?’ The roll-call proceeded, and as the clerk’s call went slowly down the list, knots of members gathered around their fellows who were keeping tally; and a group of Copperheads hung around [George H.] Pendleton, looking gloomy, black and sour. Occasionally, when a member whose opposition to the amendment had been notable voted ‘aye,’ a clatter of applause, irrepressible and spontaneous, swept through the House. When the name of John Ganson, a New York Peace Democrat, gave back an echo of ‘aye,’ much to the surprise of everybody, there was a great burst of enthusiasm; for this marked the safety of the amendment. On the final vote there were one hundred and nineteen in the affirmative, fifty-six in the negative and eight absentees.

When the roll-call was concluded, Speaker Colfax exercised his prerogative and asked the clerk to call his name, whereon his voice rang out with an ‘aye.’ Then, the record being made up, the Speaker, his voice trembling, said: ‘On the passage of the Joint Resolution to amend the Constitution of the United States the ayes have 119, the noes 56. The constitutional majority of two thirds have voted in the affirmative, the Joint Resolution has passed.’ For a moment there was a pause of utter silence, as if the voices of the dense mass of spectators were choked by strong emotion. Then there was an explosion, a storm of cheers, the like of which probably no Congress of the United States ever heard before. Strong men embraced each other with tears. The galleries and aisles were bristling with standing, cheering crowds. The air was stirred with a cloud of women’s handkerchiefs waving and floating; hands were shaking; men threw their arms about each other’s necks, and cheer after cheer, and burst after burst followed. Full ten minutes elapsed before silence returned sufficient to enable Ebon C. Ingersoll, of Illinois, to move an adjournment ‘in honor of the sublime and immortal event,’ upon which B.C. Harris, the deeply censured Marylander, shaking with wrath, arose and demanded the ayes and noes on the motion. This little artifice to procure delay did not amount to much, for, as the roll call began, members answered to their names and passed out, most of the defeated Copperheads taking their hats and stealing away before their names were reached. As the roll call went on amidst great confusion (for there was no longer any pretense of maintaining order), the air was rent by the thunder of a great salute fired on Capitol Hill, to notify all who heard that slavery was no more.

Every Republican of the House voted for the final passage of the amendment; not one of them was absent when the vote was taken. Of the 199 members who finally voted for the amendment, 10 were Democrats; their votes were necessary to secure the constitutional two thirds. These men were James E. English, of Connecticut; Anson Herrick, William Radford, Homer A. Nelson, John B. Steele, and John Ganson, of New York; A.H. Coffrotoh and Archibald McAllister, of Pennsylvania; Wells A. Hutchins, of Ohio; and Augustus C. Baldwin, of Michigan. There were 8 Democrats absent when the vote was taken; these were Jesse Lazear, of Pennsylvania; John F. McKinney and Francis C. LeBlond, of Ohio; Daniel W. Voorhees and James F. McDowell, of Indiana; George Middleton and A. J. Rogers, of New Jersey; and Daniel Marcy, of New Hampshire. It is fair to assume that these absentees were not unwilling that the amendment abolishing slavery should prevail, but were not willing to give it their active support.6

According to Congressman Isaac Arnold: “The vote on the passage of the resolution was taken amidst the most intense anxiety and solicitude. Up to the last roll no one knew what the results would be. Democratic votes were needed to carry the measure. We knew we should get some, but whether enough none could tell. The most intense anxiety was felt, and as the clerk called the names of members, so perfect was the silence that the sound of a hundred pencils, keeping tally as the names were called and recorded, could be heard. When the name of Governor English, a democrat from Connecticut, was called, and he voted aye, there was great applause on the floor and in the crowded galleries, and this was repeated when Ganson, Nelson, Odell and other democrats from New York responded aye. The clerk handed the vote to the speaker, Colfax, who announced in breathless silence the results: Ayes, one hundred and nineteen, noes, fifty-six. Every negative vote was given by a democrat.”7

Historian James M. McPherson wrote: “When the result was announced, Republicans on the floor and spectators in the gallery broke into prolonged – and unprecedented – cheering, while in the streets of Washington cannons boomed a hundred-gun salute. The scene ‘beggared description,’ wrote a Republican congressman in his diary. ‘Members joined in the shouting and kept it up for some minutes. Some embraced one another, others wept like children. I have felt, ever since the vote, as if I were in a new country.’ By acclamation the House voted to adjourn for the rest of the day ‘in honor of this immortal and sublime event.'”8

Arnold reported: “When the speaker made the formal announcement: ‘The constitutional majority of two thirds having voted in the affirmative, the joint resolution is passed,’ it was received with an uncontrollable outburst of enthusiasm. The republican members, regardless of the rules, instantly sprang to their feet and applauded with cheers. The example was followed by the spectators in the galleries, who waved their hats and their handkerchiefs, and cheers and congratulations continued for many minutes. Finally, Mr. [Eben C.] Ingersoll of Illinois, representing the district of Owen Lovejoy, in honor, as he said, of the sublime event, moved that the House adjourn. The motion was carried, but before the members left their seats the roar of artillery from Capitol Hill announced to the people of Washington that the amendment had passed Congress.”9

After passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, according to Congressman George W. Julian, “The cheering in the hall and densely packed galleries exceeded anything I ever saw before and beggared description…Members joined in the shouting and kept it up for some minutes. Some embraced one another, others wept like children.” According to Congressman Arnold, “The personal friends of Mr. Lincoln, hastening to the White House, exchanged congratulations with him on the auspicious result. The passage of the resolution filled his heart with joy. He saw in it the complete consummation of his own great work, the emancipation proclamation.”10

President Lincoln, however, committed a constitutional faux pas. He signed the Thirteenth Amendment – a step which wasn’t required by the Constitution since no presidential approval is necessary for an amendment to be submitted to states for ratification. Contemporary journalist Noah Brooks wrote that “the signature of the President was not necessary to give effect to the action of Congress in passing the amendment. Inadvertently, however, the Joint Resolution was laid before the President on the day of its passage by the House, and he signed it in due course of business. Subsequently, however, the Senate, at the instance of Senator Lyman Trumbull, who was a gifted hair-splitter, adopted a resolution that such approval by the President was unnecessary to give effect to the action of congress; and it was then declared that the negative of the President applied only to the ordinary cases of legislation, and that he had nothing to do with the proposition or the adoption of amendments to the Constitution. Nevertheless, the attaching of the President’s signature to the Thirteenth Amendment did establish for him a precedent which thereafter required him to sign his name to the hundreds of facsimiles of the document which set forth the momentous fact that Congress had on the thirty-first day of January, 1865, formally abolished slavery throughout the United States; and he was deeply gratified that his name was officially connected with that act.”11

It was ironic that President Lincoln signed the amendment by mistake – after worrying on January 1, 1863 that his hand might quiver while signing the Final Emancipation Proclamation because he had been shaking hands for three hours. But perhaps, the signature was a happy slip of the pen. “Concerning this amendment there is a unique matter – namely, the President of the United States put his signature to it. That caused a little trouble when the Senate had to pass a resolution saying it was not necessary and he should not have done it,” wrote historian Roy P. Basler. “There has been speculation as to why and how this happened. My guess is that since it had been more than a half century since there had been an amendment, nobody knew, including Lincoln that he wasn’t supposed to sign it when it was passed. Since he signed everything else that both Houses passed, he thought he should also sign this….There may be another supposition, that certainly there wasn’t anything passed by Congress during Lincoln’s presidency which he would more gladly have set his signature to, and which he probably wanted to set his signature to, more than the Thirteenth Amendment.”12

Biographer Isaac Arnold wrote of the celebration: “On the following evening a vast crowd of rejoicing and enthusiastic friends, with music, marched to the White House, publicly to congratulate the President on the passage of the joint resolution. Arriving at the Executive Mansion, the band played national airs, and as Mr. Lincoln appeared at the window over the portico he was greeted with the greatest enthusiasm. When the cheering had subsided, he raised his arm, and, with every feature radiant with joy slowly said: “The great job is ended.”13 The New York Tribune reported:

The President said he supposed the passage through Congress of the Constitutional amendment for the abolishment of Slavery throughout the United States, was the occasion to which he was indebted for the honor of this call. [Applause.] The occasion was one of congratulations to the country and to the whole world. But there is a task yet before us – to go forward and consummate by the votes of the States that which Congress so nobly began yesterday. [Applause and cries – “They will do it,” &c.] He had the honor to inform those present that Illinois had already to-day done the work. [Applause.] Maryland was about half through; but he felt proud that Illinois was a little ahead. He thought this measure was a very fitting if not indispensable adjunct to the winding up of the great difficulty. He wished the reunion of all the States perfected and so effected as to remove all causes of disturbance in the future; and to attain this end it was necessary that the original disturbing cause should, if possible, be rooted out. He thought all would bear him witness that he had never shrunk from doing all he could to eradicate Slavery by issuing an emancipation proclamation. [Applause.] But that proclamation falls far short of what the amendment will be when fully consummated. A question might be raised whether the proclamation was legally valid. It might be added that it only aided those who came into our lines and that it was inoperative as to those who did not give themselves up, or that it would have no effect upon the children of the slaves born hereafter. In fact it would be urged that it did not meet the evil. But this amendment is a King’s cure for all the evils. [Applause.] It winds the whole thing up. He would repeat that it was the fitting if not indispensable adjunct to the consummation of the great game we are playing. He could not but congratulate, himself, the country and the whole world upon this great moral victory.14

William Lloyd Garrison, Jr., reported on the biracial celebration on February 4 at the Music Hall in Boston which ended with “Sound the Loud Timbrel” being sung: “It was a scene to be remembered – the earnestness of the singer, pouring out his heartfelt praise, the sympathy of the audience, catching the glow & the deep-toned organ blending the thousand voices in harmony. Nothing during the evening brought to my mind so clearly the magnitude of the act we celebrated, its deeply religious as well as moral significance than ‘Sound the loud timbrel o’er Egypt’s dark sea, Jehovah has triumphed, His people are free.'”15

President Lincoln took great pride in the fact that Illinois was the first state to ratify the Thirteenth Amendment – on February 1, 1865, only one day after the House had passed it. But noted fellow Illinoisan Isaac Arnold, “it was the brave heart, the clear, sagacious brain, the indomitable but patient will of Abraham Lincoln that carried through the great revolution.”16 Contemporary journalist Noah Brooks wrote:

Now that the amendment, however having safely passed the ordeal of both branches of Congress, was to go to the States for ratification, the final act giving vitality to the amendment was merely a matter of time. Two States, Rhode Island and Michigan, led the column, their legislatures having ratified the amendment February 2, 1865; but it was not until after Lincoln’s death that the necessary three fourths of the thirty-six States of the Union had ratified the amendment so that it became valid as a part of the Constitution [33 out of 36 states ratified]. Official proclamation of that consummation was finally made by Secretary Seward, then in Johnson’s cabinet, December 18, 1865.

Before the adoption of the Thirteen Amendment, slavery was possible within the limits of any State, at the will of a majority of the voters of such State; or, slavery could be abolished in any State in like manner. Now, slavery was forever prohibited within the United States by the authority of the nation. And as the amended Constitution declared that ‘Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation,’ the power of the States to meddle with the question of slavery was forever taken away. In September 1859, Lincoln compressed into a single brief sentence the gist of the Dred Scott decision thus: ‘The Constitution of the United States forbids Congress to deprive a man of his property without due process of law. The right of property in slaves is distinctly affirmed in the Constitution: therefore, if Congress shall undertake to say that a man’s slave is no longer his when he crosses a certain line into a Territory, that is depriving him of his property without due process of law.’ The Thirteenth Amendment, proposed by Congress and adopted by the States, drew the fangs of the monster which [Roger] Taney, and those who believed with him, had insisted was sleeping in the Constitution – the right of property in slaves.17

Historian Kenneth Stamp wrote: “Lincoln’s wholehearted support was crucial in getting that vote reversed the following January. Responding to a serenade after the passage of the amendment, he congratulated the country ‘upon this great moral victory.’ Lincoln had indeed become the Great Emancipator, and William Lloyd Garrison concluded that he was more than a ‘wet rag’ after all. In a letter, dated February 13, 1865, Garrison commended him warmly for the part he had played in the final abolition of slavery: ‘As an instrument in [God’s] hands,’ he wrote, ‘you have done a mighty work for the freedom of millions…in our land….I have the utmost faith in the benevolence of your heart, the purity of your motives, and the integrity of your spirit.”18

The Thirteen Amendment to the Constitution was ratified on December 18, 1865 when the required three-fourths of all states – 27 – had approved it. In the words of Lincoln biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay, “The ‘new birth of freedom,’ which Lincoln invoked for the nation in his Gettysburg address, was accomplished.”19

Footnotes

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory 1864-1865, p. 213.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best: Noah Brooks, p. 185-186.

- Ralph Korngold, Thaddeus Stevens: A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great, p. 231.

- Earl Schenck Miers, The Last Campaign: Grant Saves the Union, p. 163.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865, p. 213.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best: Noah Brooks, p. 186-188.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 365.

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 839-840.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 365-366.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 365-366.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best: Noah Brooks, p. 190-191.

- Roy P. Basler, A Touchstone for Greatness, p. 201.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 366.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 255 (February 1, 1865).

- James M. McPherson, The Negro’s Civil War, p. 52-53 (Letter from William Lloyd Garrison, Jr. To W.E. Garrison, February 5, 1865).

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 366.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best: Noah Brooks, p. 189-190.

- Gabor S. Boritt, editor, Lincoln the War President, p. 142 (Kenneth M. Stampp, “The United States and National Self-determination”).

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume X, p. 90.