Before the end of the 1847-1848 congressional session, Mr. Lincoln commented on the upcoming presidential contest and slavery on the House floor. “Our democratic friends seem to be in great distress because they think our candidate for the President don’t suit us. Most of them can not find out that Gen: Taylor has any principles at all; some, however, have discovered that he has one, but that one is entirely wrong. This one principle, is his position on the veto power….”1 Later in his speech, Congressman Lincoln said: ” I have said Gen: Taylors position is as well defined, as is that of Gen: Cass. In saying this I admit I do not certainly know what he would do on the Wilmot Proviso. I am a Northern man, or rather a Western free state man, with a constituency I believe to be, and with personal feelings I know to be, against the extension of slavery. As such, and with what information I have, I hope and believe, Gen: Taylor, if elected, would not veto the Proviso. But I do not know it. Yet, if I knew he would, I still would vote for him. I should do so, because, in my judgment, his election alone, can defeat Gen: Cass; and because, should slavery thereby go to the territory we now have, just so much will certainly happen by the election of Cass; and, in addition, a course of policy, leading to new wars, new acquisitions of territory and still further extensions of slavery. One of the two is to be President; which is preferable?”2

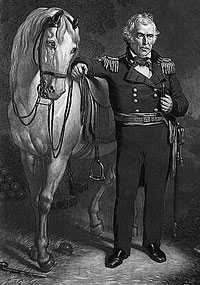

At the end of the session, according to historian Reinhard H. Luthin, “Lincoln remained in Washington for several weeks, franking campaign documents and corresponding with Whigs” to promote the presidential campaign of General Zachary Taylor whose popularity was based on his victories in the Mexican-American War.3 In September, Mr. Lincoln left for New England where he attended the Whig convention in Worcester. Edward Pierce recalled of the Worcester speech that Congressman Lincoln “devoted his attention to the question of the coming presidential election, and was not unwilling to ex[c]hange with all whom he might meet the ideas to which he had arrived…The first part of his speech was a reply, at some length, to the charge that General Taylor had no political principles; and he maintained that the General stood on the true Whig principle, that the will of the people should prevail against executive influence or the veto power of the President.”4 Mr. Lincoln told the Whig meeting in Worcester on September 12:

Mr. Kellogg then introduced to the meeting the Hon. ABRAM [sic] LINCOLN, whig member of Congress from Illinois, a representative of free soil.

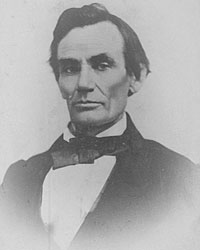

MR. LINCOLN has a very tall and thin figure, with an intellectual face, showing a searching mind, and cool judgment. He spoke in a clear and cool, and very eloquent manner, for an hour and a half, carrying the audience with him in his able arguments and brilliant illustrations – only interrupted by warm and frequent applause. He began by expressing a real feeling of modesty in addressing an audience ‘this side of the mountains,’ a part of the country where, in the opinion of the people of his section, everybody was supposed to be instructed and wise. But he had devoted his attention to the question of the coming Presidential election, and was not unwilling to exchange with all whom he might meet the ideas to which he had arrived.

He then began to show the fallacy of some of the arguments against Gen. Taylor, making his chief theme the fashionable statement of all those who oppose him, (‘the old Locofocos as well as the new’) that he has no principles, and that the whig party have abandoned their principles by adopting him as their candidate. He abandoned their principles by adopting him as their candidate. He maintained that Gen. Taylor occupied a high and unexceptionable whig ground, and took for his first instance and proof of this his whig ground, and took for his first instance and proof of this his statement in the Allison letter – with regard to the Bank, Tariff, Rivers and Harbors, &c.- that the will of the people should produce its own results, without Executive influence. The principle that the people should do what – under the constitution – they please, is a whig principle. All that Gen. Taylor does in not only to consent, but to appeal to the people to judge and act for themselves. And this was no new doctrine for Whigs. It was the ‘platform’ on which they had fought all their battles, the resistance of Executive influence, and the principle of enabling the people to frame the government according to their will. Gen. Taylor consents to be the candidate, and to assist the people to do what they think to be their duty, and think to be best in their natural affairs, but because he don’t want to tell what we ought to do, he is accused of having no principles. The Whigs here [have?] maintained for years that neither the influence, the duress, or the prohibition of the Executive should control the legitimately expressed will of the people; and now that on that very ground, Gen. Taylor says that he should use the power given him by the people to do, to the best of his judgment, the will of the people, he is accused of want of principle, and of inconsistency in position.

Mr. Lincoln proceeded to examine the absurdity of an attempt to make a platform or creed for a national party, to all parts of which all must consent and agree, when it was clearly the intention and the true philosophy of our government, that in Congress all opinions and principles should be represented, and that when the wisdom of all had been compared and united, the will of the majority should be carried out. On this ground he conceived (and the audience seemed to go with him) that General Taylor held correct, sound republican principles.

Mr. Lincoln then passed to the subject of slavery in the States, saying that the people of Illinois agreed entirely with the people of Massachusetts on this subject, except perhaps that they did not keep so constantly thinking about it. All agreed that slavery was an evil, but that we were not responsible for it and cannot affect it in States of this Union where we do not live. But, the question of the extension of slavery to new territories of this country, is a part of our responsibility and care, and is under our control. In opposition to this Mr. L. believed that the self named ‘Free Soil’ party, was far behind the Whigs. Both parties opposed the extension. As he understood it the new party had no principle except this opposition. If their platform held any other, it was in such a general way that it was like the pair of pantaloons the Yankee pedlar offered for sale, ‘large enough for any man, small enough for any boy.’ They therefore had taken a position calculated to break down their single important declared object. They were working for the election of either Gen. Cass or Gen. Taylor.

The Speaker then went on to show, clearly and eloquently, the danger of extension of slavery, likely to result form the election of General Cass. To unite with those who annexed the new territory to prevent the extension of slavery in that territory seemed to him to be in the highest degree absurd and ridiculous. Suppose these gentlemen to prevent the extension of slavery to New Mexico and California, and Gen. Taylor, he confidently believed, would not encourage it, and would not prohibit its restriction. But if Gen. Cass was elected, he felt certain that the plans of farther extension of territory would be encouraged, and those of the extension of slavery to New Mexico and California, and Gen. Taylor, he confidently believed, would not encourage it, and would not prohibit its restriction. But if Gen. Cass was elected, he felt certain that the plans of farther extension of territory would be encouraged, and those of the extension of slavery would meet no check.5

Mr. Lincoln subsequently gave speeches to Whig gatherings throughout eastern Massachusetts before arriving in Boston to speak at Tremont Temple. Lincoln biographer Ida Tarbell wrote: “Only a few days before Lincoln arrived a great convention of free soilers and bolting Whigs had been held in Tremont Temple and its earnestness and passion had produced a deep impression. Sensitive as Lincoln was to every shade of popular feeling and conviction the sentiment in New England stirred him as he had never been stirred before, on the question of slavery. Listening to Seward’s speech in Tremont Temple, he seems to have had a sudden insight into the truth, a quick illumination; and that night, as the two men sat talking, he said gravely to the great anti-slavery advocate: “Governor Seward, I have been thinking about what you said in your speech. I reckon you are right. We have got to deal with this slavery question, and got to give much more attention to it hereafter than we have been doing.”6 Mr. Lincoln’s own speech to the Boston gathering was less successful, according to historian Reinhard H. Luthin and “indicated no promise of his future fame as an anti-slavery leader.”7

Footnotes

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume I, p. 501 (Speech in the U.S. House of Representatives on the Presidential Question, July 27, 1848).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume I, p. 505 (Speech in the U.S. House of Representatives on the Presidential Question, July 27, 1848).

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 106.

- Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, editor, Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, p. 689.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 1-5 (September 12, 1848).

- Ida M. Tarbell, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume I, p. 224.

- Reinhard H. Luthin, The Real Abraham Lincoln, p. 107.