Historian Marvin Cain wrote: “The Negro troops so enlisted were not given a bounty, but instead received only laborer’s pay, thus serving for $6 a month less than white soldiers. Angered by this discrimination, Governor John Albion Andrew of Massachusetts, who was enthusiastically raising Negro regiments, initiated a test case involving Samuel Harrison, a colored chaplain in the 54th Massachusetts Infantry. Harrison, upon Andrew’s urging, applied for equal pay and allowances, retroactive to the date he entered the Army. In March, 1864, Senator Sumner delivered Harrison’s petition, along with a letter from Andrew, to Lincoln who, in turn, presented the papers to [Attorney General Edward] Bates. Torn by conflicting emotions, Bates came to the only conclusion he could, since the Negroes were in the field, fighting for the Union. Negroes mustered into service under the provisions of the Militia Act of July 17, 1862, or those freed before April 19, 1864, he declared, were entitled to equal pay and allowances. Lincoln, however, held up the decision while Congress debated the matter. On June 15, 1864, a bill was passed, providing for equal pay for Negro soldiers included in the categories Bates had specified, retroactive to January 1, 1864.1

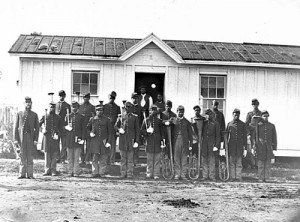

It was a particularly nettlesome issue for soldiers serving in the United States Colored Troops (USCT). “The Lincoln administration and the more liberal elements in Congress made a serious judgmental error on the issue of equal pay. When it became apparent that the law as it existed did not provide black and white soldiers with the same pay, politicians dragged their feet in seeking a solution, in the hopes that discriminatory pay would make the concept of black soldiers more tolerable to the Northern public. In fact, it appeased no one. Whites who opposed black enlistment recognized unequal pay for what it was, a sop, and the issue merely infuriated blacks and Northern whites who endorsed the policy of the USCT,” wrote historian Joseph T. Glatthaar in Forged in Battle, the Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers.2

“Why are we not worth as much as white soldiers,” asked one man enlisted in the black Massachusetts 54th Regiment, writing in a letter to his family. “We do the same work they do, and do what they cannot. We fight as well as they do. Have they forgotten James Island? Just let them think of the charge at Fort Wagner, where the colored soldiers were cruelly murdered by the notorious rebels. Why is it that they do not want to give us our pay when they have already witnessed our deeds of courage and bravery?”3 While the issue was debated in Congress, the families of such black recruits were suffering. A black soldier from Tennessee wrote Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton in April 1864 that “we have never been paid more than Seven Dollars per Month[.] They now say that is all we are allowed by the Govornment [sic] of the United States[.] Many of these people have Families to support and no other means of doing than what they get in this way.”4

Historian Glatthaar wrote: “One politician who made a genuine effort to right the wrong was Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew. Andrew felt the government’s stand on unequal pay was absolutely ridiculous: ‘For fear the uniform may dignify the enfranchised slave, or make the black man seem like a free citizen, the government means to disgrace and degrade him, so that he may always be in his own eyes, and in the eyes of all men.”5 According to Noah Andre Trudeau in Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War, 1862-1865, “In a personal effort to resolve this question, and after appeals to Washington had failed, Massachusetts Governor John A. Andrew convinced his legislature to make up the pay difference for the 54th and 55th Regiments Massachusetts Infantry (Colored). However, in his humanitarian rush to right a financial wrong, Andrew overlooked the moral issue at the heart of the matter, a point not missed by Corporal James Henry Gooding of the 54th when he wrote to the New Bedford Mercury on November 21 [1863]:

[We are] not surprised at the solicitude of the Governor to have us paid that we have so dearly earned, nor would we be surprised if the State would cheerfully assume the burden; but the Governor’s recommendation clearly shows that the General Government don’t mean to pay us, so long as there is a loophole to get out of it, and that is what surprises us, a government that won’t recognize a difference between volunteers in good faith, and a class thrown upon it by the necessities of war….A man who can go on the field counts, whether he be white or black, brown or grey; and if Massachusetts don’t furnish the requisite number, why she must submit to a draft. But, we as soldiers, cannot call in question the policy of the government, but as men who have families to feed, and clothe, and keep warm, we must say, that the ten dollars by the greatest government in the world is an unjust matter on the ground that we are not soldiers would be simply absurd, in the face of the existing facts. A soldier’s pay is $13 per month, and Congress had nothing to do but to acknowledge that we are such– it needs no further legislation. To say even, we were not soldiers and pay us $20 would be injustice, for it would rob a whole race of their title to manhood.6

Governor Andrew was unrelenting in his support of recruitment of black soldiers and his advocacy of them once recruited. He wrote President Lincoln in late May 1864, laying out the legal case for equal pay for equal military service:

I have the honor to introduce to you Geo S. Hale, Esq. President of the Common Council of the City of Boston, who is charged by me with the duty of presenting to you the matter of the payment of the 54th, and 55th Regiments of Massachusetts Volunteers. I feel compelled again and again to ask your Excellency’s attention to this, not only by reason of the suffering condition of the men of these regiments and of their families, but also from my conviction of their rights under the laws, and of the justice of their claim.

I avail myself of this opportunity, to add the statement of a piece of important historical evidence to what I have heretofore urged both orally and in writing. I allude to the authority of the precedent established by contemporaneous construction of the Acts of Congress of Dec. 12 1811, Jan. 11 1812, and Dec. 1814 on the part of the Government, and also the authority of the interpretation of those Statutes contained in the official opinion of Mr. Wirt, given in 1823, (and found in Vol. 1, on pages 602 3) of the published opinions of the Atty. Genl of the U. S. Under these acts which called for the enlistment of soldiers into the army of the U. S. one of which required such soldiers to be “able bodied, effective men” and another required them to be “free, effective able bodied men”, it is shown that colored men of African descent were enlisted and mustered into the Army; – and that they were paid and in all other respects treated as were other soldiers. Besides in the “opinion” alluded to, Mr. Wirt decided that they were entitled to the same bounty which white soldiers received under the same acts of Congress. It appears, therefore, that under the law for recruiting the regular Army colored men were enlisted, paid and enjoyed the bounties accorded to men of the white race. Thus half a century ago, neither Congress nor the Executive Department, nor the People saw cause to deny the wages of a soldier to any men who wore the uniform, took the oaths and performed the duties of a soldier: – not even though he was black.

It must be remembered that then the laws did not in express words and by set phrase recognize colored men as soldiers. But the terms used in the Acts of Congress were such as would be satisfied by persons of color. Now, not only do the laws authorizing the President to accept Volunteers, use terms which are satisfied by men of color, as that they are by construction, to be deemed included therein; but, Congress did by express act, in set terms, on the 17th day of July 1862 authorize the President to employ such persons for the suppression of the rebellion, [Ch. 195, Sec. 11 of Acts of 1862], and without any limitation of manner (saving of course that it must be in a manner known to the laws) – and without any limitation as to pay.

I confess that as a lawyer I cannot conceive a clearer case of legal right, under a contract, than is the case presented by the soldiers whose claims I present. Their moral claims to consideration and regard, I am sure I need not repeat nor urge anew.7

About the same time, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner wrote President Lincoln: “The Senate attached its Bill to equalize pay – as an amendment to the Army appropriation Bill. This bill is identical with the first two pages which you showed me last evng.” He added. “Should the House amendment prevail, it would, probably, exclude most persons in the two S. C. regiments & also in the La[.] regiments from its benefits; but it would cover the Mass. regiments.”8

On June 15, 1864, legislation requiring equal pay was passed in the army appropriations bill. Attorney General Edward Bates wrote President a few days after passage of the equal-pay legislation. He expressed his bafflement of the law’s impact on black soldiers and on himself:

On Saturday afternoon I had the honor to receive your letter of the 17th (Friday), with a copy of the act of Congress of June 15. 1864, and a request for my opinion upon a question “in reference to what pay, bounty and clothing is allowed by law, to persons of color who were free on the 19th day of April 1861, and who have been enlisted and mustered into the military service of the United States, between the month of December 1862, and the 16th of June 1864.”

I confess myself at a loss to know (so as to answer satisfactorily to myself) the precise meaning of the question, or the precise point upon which a doubt exists in your Department, as to the amount of pay, bounty and clothing of the persons indicated, under laws passed prior to the 15th of June 1864.

I am the more induced to desire a specific statement of the question, because the 4th section of the act (of June 15. 1864) to which you refer, is very peculiar in its phraseology. It does not give, or purport to give to the class of troops indicated, any thing whatever, to which they had not a perfect right, by prior laws. It provides only that they shall “be entitled to receive the pay, bounty and clothing allowed to such persons by the laws existing at the time of their enlistment.” It seems to me therefore that any question as to the amount of pay, bounty and clothing to be paid to such troops, must, of necessity, arise under the previous laws, and not under the act of June 15. 1864. And I should be ready to comply, with alacrity, with your request for an opinion upon any specific question of law, arising under any of those prior acts.

But the said 4th section is very peculiar, in another respect. It does not require the Attorney General to give any opinion to any officer. That is amply provided for by other statutes, which make it his duty, in the cases specified, to give “opinion and advice” to the President and the Heads of Departments. But it goes far beyond that. It purports to make him a final judge of the matter, by enacting that “the Attorney General of the United States is hereby authorized to determine any question of law arising under this provision ” i.e. this 4th section. And this is clearly a new and special delegation of power, to hear and determine questions of law, without and beyond the general duty of the Attorney General, to give opinion and advice to the President and the heads of Departments.

I make these suggestions sir, upon the supposition that there may be questions arising under the acts prior to that of June 15. 1864, touching the pay, bounty, and clothing of the persons indicated, and that, if so, you will be pleased to direct the question to be so stated as to enable me to give direct and specific answers, which I will endeavor to do, with all convenient speed.9

Four days later, President Lincoln replied: “By authority of the Constitution, and moved thereto by the fourth section of the act of Congress entitled “An act making appropriations for the support of the Army for the year ending the thirtieth of June, Eighteen hundred and sixty five, and for other purposes,” approved, June 15th 1864, I require your opinion in writing as to what pay, bounty, and clothing are allowed by law to persons of color who were free on the 19th day of April, 1861, and who have been enlisted and mustered into the military service of the United States between the month of December, 1862 and the 16th of June 1864. Please answer as you would do, on my requirement, if the act of June 15th 1864 had not been passed; and I will so use your opinion as to satisfy that act.”10 Neither the act or Bates response instantaneously solved the economic woes of black soldiers. In August, a black soldier from New York serving in Louisiana wrote the President to let him know “that you have Proven A friend to me and to all our Race.” But he complained that his wife and three children were destitute because he couldn’t collect his pay and send it to her. He wrote that “it go[e]s very hard with me to think my family should be At home A suffering have money earnt and cant not get it[.] And I don’t know when it will Be Able to Releave my suffering Family{.]”11

Black soldiers were not only discriminated against with pay, they generally excluded from promotion to officer rank. “There were two reasons why nearly all officers of black regiments were white: (1) At first few African-Americans had the experience necessary to serve as officers, and (2) race prejudice was still so strong in the North in 1863 that public opinion strongly opposed the elevation of blacks to officer’s rank,” wrote historian James M. McPherson.12Despite black protests, “few than 100 African-Americans were commissioned during the war, mostly as lieutenants. There were no black officers in the navy,” according to McPherson.”13

But by the war’s end, pay equality had been implemented and a large measure of political economic equality seemed promised. Historian LaWanda Cox wrote that “Lincoln perceived military service as affording blacks an opportunity to attain a larger measure of equality. In mid-century, both friend and foe of racial equality recognize a close historic linkage between bearing arms and citizenship.”14

Footnotes

- Marvin R. Cain, Edward Bates of Missouri, p. 234.

- Joseph T. Glatthaar, Forged in Battle, the Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers, p. 172.

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 92.

- Joseph T. Glatthaar, Forged in Battle, the Civil War Alliance of Black Soldiers and White Officers, p. 172.

- Noah Andre Trudeau, Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War, 1862-1865, p. 92-93.

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 95.

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 96.

- LaWanda Cox, Lincoln and Black Freedom, p. 23.

- Ira Berlin, Barbara J. Fields, Steven F. Miler, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, editor, Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War, p. 467-468 (Letter from William J. Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, April 27, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from John A. Andrew to Abraham Lincoln, May 27, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Charles Sumner to Abraham Lincoln, May 23, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Edward Bates to Edwin M. Stanton, June 20, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Edward Bates [Copy in a Secretarial Hand]1, June 24, 1864).

- Ira Berlin, Barbara J. Fields, Steven F. Miler, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, editor, Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War, p. 475-475 (Letter from George Rodgers to Abraham Lincoln, July 31, 1863).

Visit