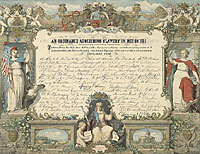

On August 30, 1861, General John Frémont1 declared martial law in Missouri. He also ordered the emancipation of slaves in the state. Historian William Earnest Smith wrote: “Fremont rose early on the morning of August 30. At dawn he called for Edward Davis of Philadelphia to come to hear him read the draft of his emancipation order ‘that first gave freedom to the slaves of rebels, and which he had thought out and written in the hours taken from his brief resting time.’ Mrs. Fremont had found him at his desk. ‘I want you two, but no others,’ said the General. He had risen to the occasion as he saw it, to make the decisive stroke to clear Missouri of the rebels who infested her. The Order was published in the Democrat on August 31. The editors called it the ‘most important document which has yet appeared in the progress of the war,’ and begged for it the support of ‘every faithful man, by every word and deed.'”2 Frémont biographer Allan Nevins wrote:

Beyond question Fremont issued his proclamation simply as a war measure in Missouri, and with little if any thought of its effect outside that state. He has been accused by [John G.] Nicolay and [John] Hay of drafting it as an appeal to the support of the northern radicals, and as a last desperate attempt to regain the popularity which he had lost through [Nathaniel] Lyon’s defeat. No foundation exists for this view, which is unjust in attributing to the impetuous General a measure of shrewd, scheming calculation which he never possessed. He planned the proclamation merely as a weapon against the guerrillas who were laying northern Missouri waste; he designed it, as he said, “to place in the hands of the military authorities the power to give instantaneous effect to existing laws, and to supply such deficiencies as the conditions of war demand.” It was characteristic of him that he did not wait to consult the Administration on so momentous a step; had he paused to think of its effect outside turbulent Missouri, he would have done so. But he did not know how fiercely the radicals and Lincoln were already at odds over emancipation.

He was warned, as he read it to his wife and friend in that gray August dawn, that Washington would be hostile. “General,” said Edward Davis, “Mr. Seward will never allow this. He intends to wear down the South by steady pressure, not by blows, and then make himself the arbitrator.” “It is for the blows, and then make himself the arbitrator.” “It is for the North to say what it will or will not allow. Replied Fremont, “and whether it will arbitrate, or whether it will fight. The time has come for decisive action; this is a war measure, and as such I make it. I have been given full power to crush rebellion in this department, and I will bring the penalties of rebellion home to every man found striving against the Union.”3

At the beginning of the Civil War, emancipation was not a popular sentiment among Union Army officers. “The few officers who did support emancipation were clearly animated by politics,” wrote historian Mark Grimsley.4 “Politically Fremont was associated with the faction of the Republican party known as the radicals, who wanted to make the abolition of slavery one of the official objectives of the war. Fremont was sincerely antislavery, and his desire to strike a blow at that institution, coupled with his opinion that Lincoln had given him a blank check, caused him to set up as a policy maker,” wrote military historian T. Harry Williams. “Like McClellan, the Pathfinder had assumed that he could define policy without consulting the government. Unlike McClellan, he had announced a policy which ran counter to the one proclaimed by the government. Lincoln and Congress, in order to keep the border slave states in the Union and to unite Northern opinion on one issue, had said the war was being conducted to restore the Union. The President knew that Fremont’s proclamation would alienate conservative support of the war; besides, he had no intention of letting generals make policy.”5 Historian Grimsley argued: “Frémont’s proclamation, although possibly influenced by a genuine sense of its military necessity, seemed politically motivated after he refused to modify it without direct presidential order.”6

Historian William E. Parrish wrote: “President Lincoln had strong reservations about two aspects of the Fremont proclamation and quickly made them known to the commander. He dispatched a special messenger to St. Louis on September 2, expressing his concern about the order to shoot those taken with arms, which he feared would lead to Confederate retaliation. He, therefore, ordered that no such action be taken without his consent. He then requested Fremont to modify his emancipation policy to conform with an August 6 act of Congress that limited emancipation to those slaves forced to take up arms or otherwise actively participate in the war on the Confederate side.”7 President Lincoln asked Frémont to bring his proclamation into conformance with the First Confiscation Act:

Two points in your proclamation of August 30th give me some anxiety. First, should you shoot a man, according to the proclamation, the Confederates would very certainly shoot our best man in their hands in retaliation; and so, man for man, indefinitely. It is therefore my order that you allow no man to be shot, under the proclamation, without first having my approbation or consent[.]

Secondly, I think there is great danger that the closing paragraph, in relation to the confiscation of property, and the liberating slaves of traiterous owners, will alarm our Southern Union friends, and turn them against us perhaps ruin our rather fair prospect for Kentucky. Allow me therefore to ask, that you will as of your own motion, modify that paragraph so as to conform to the first and fourth sections of the act of Congress, entitled, “An act to confiscate property used for insurrectionary purposes,” approved August, 6th, 1861, and a copy of which act I herewith send you. This letter is written in a spirit of caution and not of censure[.]8

Historian Benjamin P. Thomas wrote: “Frémont considered for six days. He saw no reason to amend his proclamation. He would not ‘change or shade it,’ he decided. ‘It was equal to a victory in the field.’ If the President wished to modify it, he could issue the order himself.”9 Fremont replied to President Lincoln in writing on September 8, but he also sent his own wife, Jessie, to Washington to talk to the President in person:

Your letter of the 2d, by special messenger, I know to have been written before you had received mine, and before my telegraphic despatches and the rapid development of critical conditions here, had informed you of affairs in this quarter. I had not written to you fully or frequently, first because in the incessant change of affairs I would be oposed [sic] to giving you contradictory accounts, and secondly because the amount of the subjects to be laid before you would demand too much of your time. Trusting to have your confidence I have been leaving it to events themselves to shew you whether or not I was shaping affairs here according to your ideas. The shortest communication between Washington and St. Louis generally involves two days, and the employment of two days in time of war goes largely towards success or disaster. I therefore went along according to my own judgment, leaving the result of my movements to justify me with you, and as in regard to my proclamation of the 30th. Between the rebel armies, the Provisional Government, and home traitors I felt the position bad and saw danger. In the night I decided upon the proclamation & the form of it. I wrote it the next morning and printed it the same day. I did it without consultation or advice with any one, acting solely with my best judgement to serve the country and yourself, and perfectly willing to receive the amount of censure which should be thought due if I had made a false step. It was as much a movement in the war as a battle is, and in going with these I shall have to act according to my judgement of the ground before me, as I did on this occasion. If upon reflection, your better judgement still decides that I am wrong in the article respecting the liberation of slaves I have to ask that you will openly direct me to make the correction. The implied censure will be recived [sic] by me as a soldier always should the reprimand of his chief. If I were to retract of my own accord it would imply that I myself thought it wrong and that I had acted without the reflection which the gravity of the point demanded. But I did not do so. I acted with full deliberation and upon the certain conviction that it was a measure right and necessary, and I think so still.

In regard to the other point of the proclamation to which you refer I desire to say that I do not think the enemy can either misconstrue it, or urge any thing against it, or undertake to make unusual retaliation. The shooting of men who shall rise in arms, within its lines, against an army in the military occupation of a country, is merely a necessary measure of defence and entirely according to the usages of civilized warfare. The article does not at all refer to ordinary prisoners of war, and certainly our enemies have no ground for requiring that we should waive in their benefit any of the ordinary advantages which the usages of war allow to us. As promptitude is itself an advantage in war I have to ask that you will permit me to carry out upon the spot the provisions of the proclamation in this respect. Looking at affairs from this point of view I feel satisfied that strong and vigorous measures have now become necessary to the success of our arms, & hoping that my views may have the honor to meet your approval.10

Jessie did not help her husband’s case. President Lincoln recalled: “She sought an audience with me at midnight and taxed me so violently with many things that I had to exercise all the awkward tact I have to avoid quarreling with her. She surprised me by asking why their enemy, Montgomery Blair, had been sent to Missouri. She more that once intimated that if General Frémont should conclude to try conclusions with me he could set up for himself. The next we heard was that Frémont had arrested Frank Blair and the rupture has since never been healed.”11

Historian James M. McPherson wrote: “A wiser man would have treated Lincoln’s request as an order. But with a kind of proconsular arrogance that did not sit well with Lincoln, Frémont refused to modify his proclamation without a public order to do so.”12 Frémont got one. On September 11, President Lincoln ordered Frémont to rescind his proclamation. He had in the meantime been visited by Frémont’s wife Jessie, who delivered a message from her husband near midnight on September 10. Mr. Lincoln wrote:

Yours of the 8th in answer to mine of 2nd Inst. is just received. Assuming that you, upon the ground, could better judge of the necessities of your position than I could at this distance, on seeing your proclamation of August 30th I saw perceived no general objection to it-

The particular clause, however, in relation to the confiscation of property and the liberation of slaves, appeared to me to be objectionable, in it’s [sic] non conformity to the Act of Congress passed the 6th of last August upon the same subjects; and hence I wrote you expressing my wish that that clause should be modified accordingly– Your answer, just received, expresses the preference on your part, that I should make an open order for the modification, which I very cheerfully do It is therefore ordered that the said clause of said proclamation mentioned be so modified, held, and construed, as to conform to, and not to transcend, the provisions on the same subject contained in the Act of Congress entitled “An Act to confiscate property used for insurrectionary purposes” Approved, August 6. 1861; and that said act be published at length with this order– 13

Pressure had been building on the President from residents of Border States to rescind the Fremont proclamation. Lincoln biographer Benjamin P. Thomas wrote that in Kentucky: “General [Robert] Anderson reported that a company of Union volunteers had thrown down their arms and disbanded.”14 Friend Joshua Speed passed on a letter to President Lincoln from three fellow Kentuckians: “There is not a day to lose in disavowing emancipation or Kentucky is gone over the mill dam– “15 Lincoln chronicler Lowell H. Harrison wrote: “Lincoln received a number of urgent protests and demands for repudiation of the offensive order. Joshua Speed reminded him, ‘Our Constitution and laws prohibit the emancipation of slaves among us – even in small numbers. If a military commander can turn them loose by the threat of a mere proclamation – it will be a most difficult matter to get our people to submit to it.’ Two days later Speed repeated his warning: ‘So fixed is public sentiment in this state against freeing Negroes…that you had as well attack the freedom of worship in the North or the right of a parent to teach his child to read as to wage war in the state on such principles.’ James Speed, Joshua’s brother, warned that Fremont’s foolish proclamation ‘will crush out every vistage of a union party in the state,’ and similar warnings came from other Unionists, such as Garrett Davis and Robert Anderson, in whom Lincoln had confidence.”16 Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “How Lincoln, with his usual calm sagacity, took a broader and wiser view; how with the necessity of conciliating the hesitant Kentuckians in mind, he patiently and kindly asked Fremont to modify his proclamation – this, too, is an old story.”17

Historian Bruce Tap wrote: “Believing that Kentucky’s support for the Union was pivotal to the success of the northern military effort, Lincoln thought that Frémont’s policy violated the official northern war goal, embodied in the Crittenden-Johnson resolution, to restore the Union without interference with slavery. Since the proclamation took direct aim at the institution of slavery, the president reasoned that it might alienate Kentucky residents (many of whom were slaveholders) and drive them into the Confederate camp.”18

Contemporary journalist Noah Brooks wrote that “at that time there were not a few persons who thought, when the President’s letter was made public, that Lincoln desired to have Frémont bear the brunt of the unfriendly criticism that might be made on a modification of his now famous proclamation, while Lincoln should escape that censure. Perhaps Frémont thought this. But Lincoln’s kindness of heart undoubtedly did suggest this means of escape for Frémont from the dilemma in which he had been involved. Frémont was fixed, however, in his opinions. He declined to recall or change any part of his admired proclamation…”19

“In the eyes of the antislavery radicals, Frémont at once took on heroic stature,” wrote Lincoln biographer Benjamin P. Thomas.20 Historian William Parrish wrote of Fremont’s proclamation: “Radicals applauded it as an important first step toward moving the war from one to save the Union to one to secure emancipation. Both the Missouri Democrat and Missouri Republican responded favorably to the emancipation policy, the latter conservative paper not aware of its full implications.”21 Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “The reception met by the proclamation has been described by many historians, and it is sufficient to say that it aroused the enthusiasm of radical anti-slavery elements in the North as nothing had done since the firing on Fort Sumter. New England was jubilant. From all parts of the Middle West came reports that men were saying, ‘Now the Administration is in earnest,’ or That looks like work!’ In Lincoln’s own state of Illinois the outburst of applause was such as to give the President genuine pain. The German-Americans rose en masse to this new and higher object which Fremont seemed to have given the war; recruiting increased by a sudden leap. The press of the North was almost a unit in commendation. In Chicago, the Tribune; in Washington the National Intelligencer; in Boston, the Post; and in New York, Raymond’s Times, Horace Greeley’s Tribune, and Bryant’s Evening Post all praised the proclamation in high terms. Even James Gordon Bennett’s Herald, lately on the side of the South, and the Chicago Times, which was at one time briefly suppressed as a copperhead organ, joined the chorus of approbation. George Julian, an Indiana member of Congress, later wrote that ‘it stirred and united the people of the loyal States during the ten days of life allotted it by the Government far more than any other event of the war.’ Perhaps the most extraordinary fact was that Simon Cameron, the Secretary of War, who was at his home ill, thought it an admirable stroke, and telegraphing his congratulations to Frémont, returned to his desk ready to give it hearty endorsement. He was surprised to find that Lincoln was hostile. [Charles] Sumner was enthusiastic. From that moment, Fremont became more than a general – to millions, especially in New England and among the German and Yankee of the West, he became a symbol. His name represented the crusade for the extinction of slavery.”22

The reaction of New York Tribune Editor Horace Greeley was particularly important. Greeley biographer Ralph R. Fahrney wrote: “The Tribune maintained that the Fremont proclamation, while making no direct reference to the First Confiscation Act, proceeded on the principles set forth therein. ‘We do not understand the President as at all denying the soundness of the principles upon which General Fremont acted,’ it explained, ‘nor the authority of a commanding general to do in extreme cases precisely what he did, and when demanded by the imminence of the Crisis.'”23 The Anglo-African editorialized its disappointment in President Lincoln’s decision “which hurls back into the hell of slavery the thousands in Missouri rightfully set free by the proclamation of Gen. Fremont, which deprives the cause of the Union of its chiefest hold upon the heart of the public, and which gives to the rebels ‘aid and comfort’ greater than they could have gained from any other earthly source….”24

Historian T. Harry Williams wrote: “The popular outburst indorsing this action was tremendous and instantaneous. Upon the radicals the antislavery principle of Frémont’s proclamation fell like welcome manna from heaven; it suggested the method whereby slavery could be abolished. They loudly applauded the man who had dared to strike a real blow at the hated institution. Their press warned Lincoln not to revoke a measure that must eventually become a settled policy of the government. ‘The administration’s hush-a-by-baby policy.’ rejoiced one Jacobin sheet, ‘is now necessarily about played out.'”25 President Lincoln received many letters from around the country in support of the Frémont’s order – such as this one from a Springfield friend, Erastus Wright:

I have just returned from Chicago where 25.000 were assembled at the State Fair– Freemonts [sic] Proclamation was the key note. 99 of every 100 said amen! The Laws of War Justified it, and the necessities of the case required it– It had a clear ring. God like– No crack in the bell and echoed from Kansas to Maine with universal approbation– It foreshadowed Liberty to a part, at least of Gods crushed poor– Genl Freemont has the hearts of the People, Like David under Saul (1st Samuel 18.7) The People will say Lincoln hath slain his thousands and Fremont his ten thousands– The chilling influence was great; (The Slavites rejoice) – on receiving your order to Freemont of 11. Sept./61 It came on the people like a snowstorm in June– Freemonts [sic] plans all frustrated; and He may yet resign– It doubtless had will have a very parallysing [sic] effect in all the Western Army[.] Our soldiers 50 thousand in Illinois turned out to crush Rebellion, not protect it– If Mr. [Joseph] Holt or any other, expects to Put down rebellion and at the same time protect Slavery he may find it an uphill business– Has not God a controversy now with this Nation. Are not his Judgements now heavy upon us for this identical sin– Now Friend Lincoln let me suggest to you, “It is a fearful thing to contend against the living God”-

If God has determined freedom for the Slave He will be very likely to do it – even to the Destruction of this wicked Nation. The Bible evidences are clear on this point; His heaviest Judgements have always been on the oppressors– The South enslaved the North covenanted to help keep down – and to catch if any escape– This is the record before God written in blood– The South for rob[b]ing the harmless black man got sugar coffee and bales of cotton I say the South got pay for rob[b]ing the poor[.] But the North, more despicably mean, served Old Satan for the honour of it– Is the black man in fault, is he to be rob[b]ed for being as God made him; Is he not a human being will he not stand higher in the day of Judgement than his oppressors

Sin has a dreadful blinding influence and this fact is often mentioned as peculiar to the vicinity of Washington where the rights of the black man by many Government officials are hardly recognized– This is a Horrible Sin and will surely have Horrible Judgements

Whence came that voice Saul – Saul why persecutest thou me White man – White man – why enslavest though me-

The Judgements of God will give the answer even to the destruction of this whole Nation if they persist in the abomination much longer-

The Cord of Humanity unites us to our Creator[.] If we individually or Naturally cut that cord we are gone.

With all my imperfections I love and fear my God I think I understand and also love his word– Those Slaves that Genl Mansfield, Sanford McDowell and [William] Harney sent back may have been whiped or tortured to death– Those disasters at Bethel & Bull Run I think immediately followed those events– Genl Banks Genl. Butler Genl McClellan and Genl Fremont have shown a streak of Humanity and God notices even to the falling of a sparrow – witness Genl Butler taking 2 forts without the loss of a man … Almost a miracle–

Do right[.] “Let the oppressed go free” and save yourself and save the Nation from the wrath of God and Eternal Destruction– Has not Kentucky, Has not Maryland Has not Missouri been cursed with slavery long enough Has not four millions of Gods friendless poor been crushed down long enough – long enough – long enough– If the innocent black man has been, by the united energies of 20 millions, been chained down, peeled, rob[b]ed I say if he has been rob[b]ed and chained in this Hypocritical Nation long enough In the Name of God cut the chain give him his liberty– And save yourself and save Our Nation– May God give you wisdom and grace to carry out his commands of Righteousness and his approving smiles rest and abide with you and all Your Cabinet advisers is my prayer Yes my Daily prayer before my God– 26

Abolitionists were furious at the President’s order to rescind Frémont’s declaration. In a letter to fellow Senator Zachariah Chandler, Ohio’s Benjamin Wade wrote: “What do you think of ‘old Abe’s overruling Frémont’s proclamation?” He answered his own question: “So far as I can see, it is universally condemned…and I have no doubt that by it, he has done more injury to the cause of the Union, by receding from the ground taken by Frémont, than [General Irvin] McDowell did by retreating from Bull Run.”27 According to historian T. Harry Williams, “The president’s repudiation of Frémont aroused a storm of radical criticism. Wade and Chandler were enraged. Only a person sprung from ‘poor white trash,’ Wade sneered, could have acted thus. ‘I shall expect to find in his annual message, a recommendation to Congress, to give each rebel who shall serve during the war a hundred and sixty acres of land.’ [James] Grimes declared Frémont’s proclamation ‘the only real noble and true thing done during this war.’ Sumner mourned, ‘We cannot conquer the rebels as the war is now conducted.’ Lincoln had seized dictatorial powers, he complained, ‘but how vain to have the power of a god and not to use it godlike!'”28

Illinois Senator Orville H. Browning joined the Republican chorus. The longtime Lincoln friend said one conversation on emancipation with President Lincoln was the closest to “any religious talk was in the summer or fall of 1861.” Browning, who later opposed the Emancipation Proclamation, said: “Mr Lincoln we can’t hope for the blessing of God on the efforts of our armies, until we strike a decisive blow at the institution of slavery.” The President’s reply surprised him, “Browning, suppose God is against us in our view on the subject of slavery in this country, and our method of dealing with it?” said the President. Browning later told John G. Nicolay: “I was indeed very much struck by this answer of his, which indicated to me for the first time that he was thinking deeply of what a higher power than man sought to bring about by the great events then transpiring.”29 After the July-August session of Congress, Browning went home. On September 17, Browning President Lincoln wrote to defend Frémont’s actions.

It is in no spirit of fault finding that I say I greatly regret the order modifying Genl Fremonts’ proclamation.

That proclamation had the unqualified approval of every true friend of the Government within my knowledge. I do not know of an exception. Rebels and traitors, and all who sympathize with rebellion and treason, and who wish to see the government overthrown, would, of course, denounce it. Its influence was most salutary, and it was accomplishing much good. Its revocation disheartens our friends, and represses their ardor

It is true there is no express, written law authorizing it; but war is never carried on, and can never be, in strict accordance with previously adjusted constitutional and legal provisions. Have traitors who are warring upon the constitution and laws, and rejecting all their restraints, any right to invoke their protection?

Are they to be at liberty to use every weapon to accomplish the overthrow of the government, and are our hands to be so tied as to prevent the infliction of any injury upon them, or the successful resistance of their assaults?

The proclamation also provided that “All persons who shall be taken with arms in their hands within the lines shall be tried by court martial, and if found guilty, shall be shot.”

I think there is no express statute law authorizing this, and yet, I believe, no body doubts its legality or propriety.

It does not conform to the act of Congress passed the 6th of August last, nor was it intended to; and yet it is neither revoked or modified by the order of Sept: 11th.

Is a traitor[‘]s negro more sacred than his life? and is it true that the power which may dispose absolutely of the latter, is impotent to touch the former?

I am very sorry the order was made. It has produced a great deal of excitement, and is really filling the hearts of our friends with despondency.

It is rumored that Fremont is to be superceded. I hope this is not so. Coming upon the heels of the disapproval of his proclamation it would be a most unfortunate step, and would actually demoralize our cause throughout the North West. He has a very firm hold upon the confidence of the people.

You may rely upon what I say to you. You know that I am not in the habit of becoming needlessly excited, and that I have no ends to subserve except such as will advance the good of the country, and promote your own welfare – your fortune, and your fame.

I do think measures are sometimes shaped too much with a view to satisfy men of doubtful loyalty, instead of the true friends of the Country.

There has been too much tenderness towards traitors and rebels.

We must strike them terrible blows, and strike them hard and quick, or the government will go hopelessly to pieces.30

Within three days, President Lincoln replied to his friend Browning both in detail and surprise. The President’s surprise would have been greater had he known that within a year, Browning would be a major opponent of a presidential proclamation of emancipation:

Yours of the 17th is just received; and, coming from you, I confess it astonishes me. That you should object to my adhering to a law which you had assisted in making and presenting to me less than a month before, is odd enough. But this is a very small part. Gen. Fremont’s proclamation as to confiscation of property, and the liberation of slaves, is purely political, and not within the range of military law, or necessity. If a commanding General finds a necessity to seize the farm of a private owner, for a pasture, an encampment, or a fortification, he has the right to do so, and to so hold it, as long as the necessity lasts; and this is within military law, because within military necessity. But to say the farm shall no longer belong to the owner, or his heirs, forever; and this as well when the farm is not needed for military purposes, as when it is, is purely political; without the savor of military law about it. And the same is true of slaves. If the General needs them he can seize them, and use them; but when the need is past, it is not for him to fix their permanent future condition. That must be settled according to laws made by lawmakers, and not by military proclamations. The proclamation, in the point in question, is simply “dictatorship.” It assumes that the General may do anything he pleases – confiscate the lands and free the slaves of loyal people, as well as of disloyal ones. And going the whole figure, I have no doubt would be more popular with some thoughtless people, than what he has that which has been done! But I cannot assume this reckless position; nor allow others to assume it on my responsibility. You speak of it as being the only means of saving the government. On the contrary, it is itself the surrender of the government. Can it be pretended that it is any longer the government of the U. S. – any government of constitution and laws, – wherein a General, or a President, may make permanent rules of property by proclamation?

I do not say Congress might not with propriety, pass a law, on the point, just such as General Fremont proclaimed. I do not say, I might not, as a member of Congress, vote for it. What I object to, is, that I, as President, shall expressly or impliedly, seize and exercise the permanent legislative functions of the government.

So much as to principle. Now as to policy. No doubt the thing was popular in some quarters, and would have been more so, if it had been a general declaration of emancipation. The Kentucky Legislature would not budge till that proclamation was modified; and Gen. [Robert] Anderson telegraphed me that on the news of Gen. Fremont having actually issued deeds of manumission, a whole company of our volunteers threw down their arms and disbanded. I was so assured as to think it probable that the very arms we had furnished Kentucky, would be turned against us. I think to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game. Kentucky gone, we can not hold Missouri, nor as I think, Maryland. These all against us, and the job on our hands is too large for us. We would as well consent to separation at once, including the surrender of this capitol. On the contrary, if you will give up your restlessness for new positions, and back me manfully on the grounds upon which you and other kind friends gave me the election, and have approved in my public documents, we shall go through triumphantly.

You must not understand I took my course on the proclamation because of Kentucky. I took the same ground in a private letter to the General Fremont, before I heard from Kentucky.

You think I am inconsistent because I did not also forbid Gen. Fremont to shoot men under the proclamation. I understand that part to be within military law; but I also think, and so privately wrote Gen. Fremont that it is impolitic in this, that our adversaries have the power, and will certainly exercise it, to shoot as many of our men as we shoot of theirs. I did not say this in the public letter, because it is a subject I prefer not to discuss in the hearing of our enemies.

There has been no thought of removing Gen. Fremont on any ground connected with his proclamation; and if there has been any wish for his removal on any ground, our mutual friend, Sam. Glover, can probably tell you what it was. I hope no real necessity for it exists on any ground.31

Browning’s reply is notable for the inclusion of extensive legal arguments – which helped dictate a doctrine of military necessity which later became the basis for President Lincoln’s own Emancipation Proclamation:

Yours of the 22nd instant is before me. Aware of the multitude and magnitude of your engagements, I certainly did not expect a moment of your valuable time to be consumed in replying to any communication of mine; but am, therefore, not the less obliged to you for your very interesting letter.

Occasionally, since the beginning of our troubles, I have taken the liberty of writing you, and giving my opinions, valueless as they may be, upon the great questions which agitate the Nation, and which we are bound, however difficult and distressing they may be, in some way or other to solve.

I have also, from time to time, endeavored to give you a true reflection of public sentiment, so far as it was known to me. I have been prompted to this course by a very sincere, and unaffected interest in your individual welfare, fame, and fortune, as well as by a painfully intense anxiety for the maintainance [sic] of the Constitution and the Union; the restoration of the just authority of the government, and the triumph of as holy a cause, in my judgment, as ever engaged men’s feelings and enlisted their sympathies energies.

I thought that whether the public sentiment here, and my own opinions, accorded with yours or not, you might still be not only willing, but glad to know them. I have, therefore, written to you frankly and candidly, but have, at all times, intended to be both kind and respectful; and regret it deeply if I have failed in either, as some passages in yours lead me to suspect I have. Indeed I fear I have only annoyed you. Nothing, I assure you, has been further from my purpose.

Fully appreciating the difficulties, and embarrassments of your position, I would be as ready and willing to aid and relieve you by any personal sacrifice I could make, as I would be reluctant to add to your labors and harrassments, either by fault finding or solicitations.

I have said many things to you which I have not said to others. Conscious of the great injury our cause would sustain by any weakening of the Confidence of the people in the administration, I have constantly vindicated both its men, and its measures, before the public; and when I have had complaints or suggestions to make, in regard to either, I have made them directly to you.

This, I thought, was demanded alike by the claims of friendship, and of patriotism

I am the partizan of no man. I would not sustain the nearest friend I have on earth in official misconduct, and would accord full praise to my bitterest foe in doing his duty to the Country.

In the conclusion of yours you say “Suppose you write to [General Stephen A.]Hurlbut, and get him to resign.”

I could not tell, for the life of me, whether you were serious, or whether you was Poking a little irony at me. If I thought you were in earnest I would certainly do it, as I could with great propriety, having in my possession his written pledge to resign if he drank a drop of liquor after going into the service. He has violated his pledge and behaved badly, and ought to resign.

What I said in regard to Genl. Fremont and his proclamation was in accordance with this feeling. My acquaintance with him is very limited and I have had no personal feeling in the matter.

If he was honestly and faithfully doing his duty, justice to him, and regards for the Country alike required that he should be sustained. There was much complaint and clamor against him, and, as I am not quick to take up evil report, I went twice to St Louis to see, and learn for myself all that I could. It is very probable he has made some mistakes. Most of us do; and he would be more than human if he were altogether exempt from the frailties of our nature: but, in the main, he seemed to be taking his measures wisely and well. Many of the charges against him appeared to me frivolous, and I did not know of any one who could take his position, and do better amid the surrounding difficulties; and was confident that his removal at the time, and under the circumstances, would be very damaging both to the administration, and the cause.

Hence I wrote you as I thought it my duty to do, certainly not intending any impertinent interference with executive affairs, or expecting what I said to have any greater scope than friendly suggestion.

This proclamation, in my opinion, embodies a true, and important principle which the government cannot afford to abandon, and with your permission, and with all deference to your opinions, so clearly expressed, I will venture, hastily to suggest my own views of the legal principles involved; for it is important that the law which governs the case should be certainly and clearly understood; and if you are right I am in very great error, which I ought to correct.

With your construction of the proclamation your reasoning is just, logical and conclusive, but either you have greatly misunderstood it, or I have.

According to my understanding of it, it does not touch the relations between the government and its citizens. It does not undertake to settle the rules of property between citizen and citizen. It does not deal with citizens at all, but with public enemies. It does not usurp a legislative function, but only declares a pre existing law, and announces consequences which that law had already attached to given acts, and which would ensue as well without the proclamation as with it. It was, in fact, only a declaration of intention to live up to the international law settled centuries ago, and which was as much the law without the proclamation as with it. It was neither based upon the act of Congress of Augt. 6 1861, nor in collision with it, but had reference to a totally different class of cases, provided for long ago, by the political law of Nations.

The law of the 6th August acts upon and confiscates property because of the uses to which it is applied, wholly irrespective of the question of the loyalty or dis loyalty of the owner. The property of a loyal citizen is as effectually forfeited if applied to the forbidden uses, as the property of a rebel, and the property of the traitor, in arms against the government, if not so applied, is as secure under the provisions of the statute as the property of the most loyal and devoted citizen. Rebels and loyalists stand on the same platform before the statute, and have an equality of right in no way affected by their friendship or hostility to the government.

Now, how is it with the proclamation?

As before remarked it is not based upon the statute, and has no reference whatever to the class of cases provided for by the Statute. It rests upon the well ascertained, and universally acknowledged principles of international political law as its foundation – upon the laws of war as acknowledged by all civilized Nations, and is in exact harmony with them.

The Confederate States, and all who acknowledge allegiance to the Confederate States, or take part with them, are public enemies. They are at war with the United States. Men taken in battle are held as prisoners; flags of truce pass between the hostile lines; intercourse is forbidden between certain States and parts of States; and sea ports are formally blockaded.

These things constitute war, and all the rules of war apply, and all belligerent rights attack.

What are these rules and rights?

[French legal philosopher Jean Jacques] Burlamaqui says “By a state of war, that of society is abolished; so that whoever declares himself my enemy, gives me liberty to use violence against him in infinitum, or so far as I please &c.”

The rebel States, by making war upon the United States, have dissolved the state of society which previously existed between them, and are no longer entitled to invoke the protection of the Constitution and laws which they have repudiated, and are endeavoring to destroy. All their property, both real and personal, is subject, by the law of nations, to be taken, and confiscated, and disposed of absolutely and forever by the belligerent power, without any reference whatever to the laws of society; and that as well without a proclamation to that effect as with it. A proclamation is but declaratory of the pre existing law, and gives no additional force or effect to the law.

The same author continues[:]

“The state of war, into which the enemy has put himself, and which it was in his own power to prevent, permits of itself every method that can be used against him; so that he has no reason to complain whatever we do.”

“As to the goods of the enemy, it is certain that the state of war permits us to carry them off, to ravage, to spoil, or even entirely to destroy them; for as Cicero very well observes – It is not contrary to the law of nation nature to plunder a person whom we may lawfully kill.”

“This right of spoil, or plunder extends in general to all things belonging to the enemy; and the law of Nations, properly so called, does not exempt even sacred things.”

“In general it certainly is not lawful to plunder for plunder’s sake, but it is just and innocent only, when it bears some relation to the design of the war; that is when an advantage directly accrues from it to ourselves, by appropriating these goods, or at least, when by ravaging and destroying them, we in some measure weaken the enemy.”

Is there any question that the proclamation, carried into practical effect, would tend to our advantage by greatly weakening the enemy and diminishing his ability to carry on the war, and do us injury? This enquiry, however, belongs to the expediency of the measure, which I do not propose at present to discuss, but to confine myself to the question of rightful power and authority to adopt it.

The rules of law above stated declare the rights which war gives us over the effects of the enemy in a solemn war, declared in form between two states always distinct. Do the same principles apply to, and govern a civil war?

If so then the proclamation was not an excess of authority; was not in contravention of law; was not an invasion of any right of those to whom it related, and upon whom it acted, of which they could rightfully complain.

I believe civil wars are governed by the same rules which apply to and control what are technically called solemn wars , and that these rules embrace all who take part in the war against the government, whether the state where the hostile act is committed has formally thrown off the authority of the general government or not.

I quote again from Burlamaqui. “Grotius,” says he, “pretends, that the right by which we acquire things taken in war, is so proper and peculiar to a solemn war, declared in form, that it has no force in others, as in civil wars &c., and that in the latter, in particular, there is no change of property, but in virtue of the sentence of a Judge.

We may observe, however, upon this point, that in most civil wars no common judge is acknowledged. If the state is monarchical, the dispute turns either upon the succession to the crown, or upon a considerable part of the states’ pretending that the king has abused his power, in a manner which authorized his subjects to take up arms against him

In the former case, the very nature of the cause for which the war is undertaken, occasions the two parties of the state to form, as it were, two distinct bodies, till they come to agree upon a chief by some treaty. Hence, with respect to the two parties which were at war, it is on such treaty that the right depends, which persons may have to that which was taken on either side; and nothing hinders, but this right may be left on the same footing, and admitted to take place in the same manner, as in public wars between two states always distinct.

The other case, I mean an insurrection of a considerable part of the state against the reigning prince, can rarely happen, except when that prince has given room for it, either by tyranny, or by the violation of the fundamental laws of the kingdom.

Thus, the government is then dissolved, and the state is actually divided into two distinct and independent bodies; so that we are to form here the same judgment as in the former case.

For much stronger reasons does this take place in the Civil wars of a Republican state; in which the war, immediately of itself, destroys the sovereignty, which subsists solely in the union of its members.”

It thus appears that when a state is actually divided into two distinct, and independent bodies, warring upon each other, they have no more right, as between each other, to claim the protection of the Constitution and laws of the former government, than the citizens of a foreign state, at war with us would have a right to claim such protection.

The laws of civil society, that is, municipal laws and constitutions, as regulating intercourse between the parties, and determining their mutual and relative rights are dissolved, and the only rights which can be insisted upon are belligerent rights; and one of these is the right to take, confiscate and appropriate, or dispose of as we please, absolutely and forever, all the property, of every kind and character belonging to the enemy collectively and individually.

Now, the proclamation only declares, and, I think truly, the law as to one of our belligerent rights “The property, real and personal, of all persons in the State of Missouri, who shall take up arms against the United States, or who shall be directly proven to have taken active part with their enemies in the field, is declared to be confiscated to the public use, and their slaves, if any they have, are hereby declared freemen.”

It deals with public enemies only. It is, in terms, limited to those who are warring upon the government; and as to them it, in no sense, and to no extent, modifies the pre existing law. It does not touch the loyal citizen or his rights of person or property, or at all intermeddle with the relations between him and his government or fix, or attempt to fix rules of property between the citizen and his government or between citizen and citizen. It is as limited in the class of persons upon whom it was to operate to public enemies, and was further territorially limited to the State of Missouri, and had no more application to or operation in Kentucky than in Australia.

I do not think it was an act of usurpation. I do not think it has in it any of the elements of dictatorship. I do think it was fully warranted by the laws of war, and in entire harmony with all the principles of international political law. I do further think that it is a high, important, and very valuable power which the government ought not to surrender, and without the exercise of which this war can never be brought to a successful termination. I do not speak this in reference to slaves alone, but to all property. Can the war be prosecuted upon the understanding that all the property captured from the enemy is to be held for restoration to former owners when the war is over?

If a general, in the progress of the war needs the horses of a loyal citizen for public use he may take them, but must make compensation for them, or restore them when the necessity has passed, making compensation for their use. But if he captures horses from those in arms against the government – from public enemies – are they not at his absolute disposal? May he not destroy them, sell them, or turn them loose upon the desert, according to the exigencies of the case, without accountability to any body? And if he may turn loose horses why may he not negroes? They both stand to us in the relation of property of the enemy, which we may lawfully take either to weaken him, or to strengthen ourselves. And if we have no right or power to take the negro, neither have we right or power to touch or take any other description of property belonging to our enemies. The consequence will be that while they act upon the laws of war and plunder us, and confiscate all our property, and cripple and weaken us, our hands are so tied as to disable us from touching any thing that is theirs.

If the proclamation had been limited to a confiscation of the horses and cattle of those in arms against the government and making war upon it for its overthrow, would the people of Kentucky, or any other State have objected, or would anyone have supposed there was an excess, or an abuse of power? And yet there is precisely the same right to extend it to negroes that there is to apply it to horses and cattle.

I think so valuable, so indispensable and vital a belligerent right ought not to be surrendered except upon the maturest consideration, and for the most cogent reasons.

The expediency of exercising the power is another question, and one about which men may well differ, and upon that I do not now propose to express any opinion. I did think, at the time, that it was expedient – that its influence was salutary, and that its fruit would be good, and nothing has fallen under my own observation to change that opinion.

But those who have a right to decide as well as think, have determined otherwise, and it becomes me, as well as every other good citizen, not only to submit to, but sustain that decision; and so I have done, and so I will continue to do.

This communication has grown to proportions far beyond my intentions when I commenced it, but even now it is only a glance at the important question discussed.

And now, Mr President, permit me in conclusion, in all kindness, to say that I am not conscious of any “restlessness for new positions.” For us, new positions are not necessary. A firm adherence to old ones is, and this, I am sure, you intend. Thus far I have tried “to back you manfully upon the grounds upon which you had your election.” It may be I have done it feebly, but certainly honestly and earnestly; and I will be one of the last to falter in support of either our principles, or their chosen exponent.32

Two months after issuing his emancipation proclamation, General Frémont was relieved of his command by President Lincoln. He served briefly and ineffectively in Virginia in the spring of 1862.

Footnotes

- Frémont is the general spelling of John C. Frémont’s last name. But the original spelling of documents is retained where it lacks an accent.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln, John G. Nicolay’s Interviews and Essays,, p. 5 (Conversation with Orville H. Browning, June 17, 1875).

- Allan Nevins, Fremont: Pathmarker of the West, p. 503-505.

- Mark Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War, p. 127.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln & His Generals, p. 36-37.

- Mark Grimsley, The Hard Hand of War, p. 127.

- William E. Parrish, Frank Blair, Lincoln’s Conservative, p. 121.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to John C. Frémont, September 2, 1861).

- Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 276.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from John C. Frémont to Abraham Lincoln, September 8, 1861).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 133 (December 9, 1863).

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 353.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to John C. Frémont, September 11, 1861).

- Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 275.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from J. F. Bullitt, W. E. Hughes, and C. Ripley to Joshua F. Speed, September 13, 1861).

- Lowell H. Harrison, Lincoln of Kentucky, p. 225.

- Allan Nevins, Fremont: Pathmarker of the West, p. 505.

- Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The Committee on the Conduct of the War, p. 81-82.

- Noah Brooks, Abraham Lincoln: The Nation’s Leader in the Great Struggle through which was Maintained the Existence of the United States, p. 297.

- Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 275.

- William E. Parrish, Frank Blair, Lincoln’s Conservative, p. 121.

- Allan Nevins, Fremont: Pathmarker of the West, p. 503-505.

- Ralph R. Fahrney, Horace Greeley and the Tribune in the Civil War, p. 115.

- James M. McPherson, The Negro’s Civil War, p. 42 (Anglo-African, September 21, 1861).

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 40.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Erastus Wright to Abraham Lincoln, September 20, 1861).

- Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The Committee on the Conduct of the War, p. 17 (Letter from Benjamin Wade to Zachariah Chandler, September 23, 1862).

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 40-41.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, An Oral History of Abraham Lincoln, John G. Nicolay’s Interviews and Essays, p. 5 (Conversation with Orville H. Browning, June 17, 1875).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Orville H. Browning to Abraham Lincoln, September 30, 1861).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Orville H. Browning to Abraham Lincoln, September 17, 1861).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Abraham Lincoln to Orville H. Browning, September 22, 1861).

Visit

Frank Blair (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Orville H. Browning (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Orville H. Browning (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Simon Cameron (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Simon Cameron (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Zachariah Chandler (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

John C. Frémont (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Horace Greeley (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Horace Greeley (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Horace Greeley (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

David Hunter (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Benjamin Wade (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)