Frederick Douglass first met with Mr. Lincoln in the summer of 1863 and as he later recalled “saw at a glance the justice of the popular estimate of his qualities expressed in the prefix Honest to the name Abraham Lincoln.”1 Mr. Lincoln explained his policies on black soldiers and defended his incremental steps toward black rights. Unlike with many of his white abolitionist contemporaries, the proud former slave found no hint of condescension in President Lincoln’s demeanor. Douglass later recalled:

I shall never forget my first interview with this great man. I was accompanied to the executive mansion and introduced to President Lincoln by Senator [Samuel] Pomeroy. The room in which he received visitors was the one now used by the President’s secretaries. I entered it with a moderate estimate of my own consequence, and yet there was to talk with, and even to advise, the head man of a great nation. Happily for me, there was no vain pomp and ceremony about him. I was never more quickly or more completely put at ease in the presence of a great man, than in that of Abraham Lincoln. He was seated, when I entered, in a low arm chair, with his feet extended to the floor, surrounded by a large number of documents, and several busy secretaries. The room bore the marks of business, and the persons in it, the president included, appeared to be much overworked and tired. Long lines of care were already deeply written on Mr. Lincoln’s brow, and his strong face, full of earnestness, lighted up as soon as my name was mentioned. As I approached and was introduced to him, he rose and extended his hand, and bade me welcome. I at once felt myself in the present of an honest man – on whom I could love, honor and trust without reserve or doubt. Proceeding to tell him who I was, and what I was doing, he promptly, but kindly, stopped me, saying, ‘I know who you are, Mr. Douglass; Mr. Seward has told me all about you. Sit down. I am glad to see you.’ I then told him the object of my visit; that I was assisting to raise colored troops; that several months before I had been very successful in getting men to enlist, but now it was not easy to induce the colored me to enter the service, because there was a feeling among them that the government did not deal fairly with them in several respects. Mr. Lincoln asked me to state particulars. I replied that there were three particulars which I wished to bring to his attention. First that colored soldiers ought to receive the same wages as those paid to white soldiers. Second, that colored soldiers ought to receive the same protection when taken prisoners, and be exchanged as readily, and on the same terms, as any other prisoners, and if Jefferson Davis should shoot or hang colored soldiers in cold blood, the United States government should retaliate in kind and degree without delay upon Confederate prisoners in its hands. Third, when colored soldiers, seeking the ‘bauble-reputation at the cannon’s mouth,’ performed great and uncommon service on the battlefield, they should be rewarded by distinction and promotion, precisely as white soldiers are rewarded for like services.

Douglass was not a proponent of any compromise where slavery was concerned, but his interaction with Mr. Lincoln convinced him over time of the wisdom of the President’s deliberate movements toward emancipation.

“In a speech delivered in Philadelphia only two weeks after Lincoln had dedicated the cemetery at Gettysburg, Douglass made an aggressive appeal for what he repeatedly called an ‘Abolition War,'” wrote historian David W. Blight in Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory. “Douglass felt confident that history itself had taken a mighty turn. He took the pressure off Lincoln. ‘We are not to be saved by the captain,’ he declared, ‘but by the crew. We are not to be saved by Abraham Lincoln, but by the power behind the throne, greater than the throne itself.’ The supreme ‘testing’ of that ‘government of the people’ about which Lincoln had spoken so carefully at Gettysburg [on November 19] was precisely Douglass’s subject as well. In language far more direct than Lincoln’s, Douglass announced that the ‘abolition war’ and ‘peace’ he envisioned would never be ‘completed until the black men of the South, and the black men of the North, shall have been admitted, fully and completely, into the body politic of America. Here, in late 1863, he demanded immediate suffrage for blacks. In such expressions of equality, Douglass, too, looked beyond Appomattox to the long struggle to preserve in reality and memory what the war could create.”2

Blight wrote: “In this encounter, narrated to an audience in early December 1863, Douglas constructed his own proud mutuality with Lincoln. However falteringly, by whatever unjust means blacks had to die in uniform to be acknowledged as men, Douglass was determined to demonstrate that his own ideological war aims had now become Lincoln’s as well. The ‘rebirth’ they were imagining was one both clearly understood as a terrible ordeal, but one from which there was no turning back. Douglass came away from this extraordinary meeting with the conclusions that Lincoln’s position was ‘reasonable,’ but more important, that he would go down in history as ‘Honest Abraham.'”3

Douglas himself later wrote that “I did not take Mr. Lincoln’s attentions as due to my merits or personal qualities. While I have no doubt that Messrs. Seward and Chase had spoken well of me to him, and the fact of my having been a slave, and gained my freedom, and of having picked up some sort of an education, and being in some sense a ‘self-made man,’ and having made myself useful as an advocate of the claims of my people, gave me favor in his eyes; yet I am quite sure that the main thing which gave me consideration with him was my well-known relation to the colored people of the Republic, and especially the help which that relation enabled me to give to the work of suppressing the rebellion and of placing the Union on a firmer basis than it ever had or could have sustained in the days of slavery.”4Historian David Blight wrote that if it had been activated, the Lincoln-Douglass plan “would have forged an unprecedented alliance between black leadership and federal power for the purpose of emancipation.”5

Douglass’ second meeting came one year and nine days later. Commissioner of Indian Affairs William P. Dole sent a note to President Lincoln on August 18. “Mr Fred Douglass was expected on the 11 oclock train – is yet expected to day I will send him to you when he comes.”6 The next day, Mr. Lincoln met with Douglass to discuss ways of encouraging Southern slaves to escape and enlist. Mr. Lincoln wanted Douglass to organize efforts to let Confederate slaves know that they and emancipation would be endangered if a compromise peace were achieved.

The two men discussed a letter President Lincoln had written three days earlier to the Democratic editor of the Green Bay Advocate in which the President made the case for relationship among emancipation, black soldiers and Union victory: “Why should they give their lives for us, with full notice of our purpose to betray them. Drive back to the support of the rebellion the physical force which the colored people now give, and promise us, and neither the present, nor any coming administration, can save the Union. Take from us, and give to the enemy, the hundred and thirty, forty, or fifty thousand colored persons now serving us as soldiers, seamen, and laborers, and we can not longer maintain the contest. The party who could elect a President on a War & Slavery Restoration platform, would, of necessity, lose the colored force; and that force being lost, would be as powerless to save the Union as to do any other impossible thing. It is not a question of sentiment or taste, but one of physical force, which may be measured, and estimated as horsepower, and steam power, are measured and estimated. And by measurement, it is more than we can lose, and live. Nor can we, by discarding it, get a white force in place of it. There is a witness in every white mans bosom that he would rather go to the war having the negro to help him, than to help the enemy against him. It is not the giving of one class for another. It is simply giving a large force to the enemy, for nothing in return.”7

Wisconsin Governor Alexander Randall visited the President the same day and reportedly told Mr. Lincoln: “I was in your reception room to day. It was dark. I suppose that clouds & darkness necessarily surround the secrets of state. There in a corner I saw a man quietly reading who possessed a remarkable physiognomy. I was rivetted to the spot. I stood & stared at him[.] He raised his flashing eyes & caught me in the act. I was compelled to speak. Said I, are you the President. No replied the stranger, I am Frederick Douglass.”8

Unlike Mr. Lincoln, Douglass encouraged his sons to join the Union Army – he was a leading proponent of the use of black soldiers. (He did, however, petition Mr. Lincoln to discharge a sick son from military service.) A few days later, Douglass wrote the President: “all with whom I have thus far spoken on the subject, concur in the wisdom and benevolence of the idea, and some of them think it is practicable. That every slave who escapes from the Rebel States is a loss to the Rebellion and a gain to the Loyal Cause I need not stop to argue[;] the proposition is self evident. The negro is the stomach of the rebellion.”9Ten days later, Douglass wrote the President:

Sir: Since the interview with wh[ich]. Your Excellency was pleased to honor me a few days ago, I have freely conversed with several trustworthy and Patriotic Colored men concerning your suggestion that something should be speedily done to inform the slaves in the Rebel states of the true state of affairs in relation to them…and to warn them as to what will be their probable condition should peace be concluded while they remain within the Rebel lines: and more especially to urge upon them the necessity of making their escape. All with whom I have thus far spoken on the subject, concur in the wisdom and benevolence of the Idea, and some of them think it practicable. That every slave who escapes from the Rebel states is a loss to the Rebellion and a gain to the Loyal Cause, I need not stop to argue the proposition is self evident. The negro is the stomach of the rebellion. I will therefore briefly submit at once to your Excellency – the ways and means by which many such persons may be wrested from the enemy and brought within our lines:

1st Let a general agt. be appointed by your Excellency charged with the duty of giving effect to your idea as indicated above: Let him have the means and power to employ twenty or twenty five good men, having the cause at heart, to act as his agents: 2d Let these Agents which shall be selected by him, have permission to visit such points at the front as are most accessible to large bodies of slaves in the Rebel States: Let each of the said agts have power – to appoint one subagent or more in the locality where he may be required to operate: the said sub agent shall be thoroughly acquainted with the country – and well instructed as to the representations he is to make to the slaves: – but his chief duty will be to conduct such squads of slaves as he may be able to collect, safely within the Loyal lines: Let the sub agents for this service be paid a sum not exceeding two dolls – per day while upon active duty.

3dly In order that these agents shall not be arrested or impeded in their work – let them be properly ordered to report to the General Commanding the several Departments they may visit, and receive from them permission to pursue their vocation unmolested. 4th Let provision be made that the slaves or Freed men thus brought within our lines shall receive subsistence until such of them as are fit shall enter the service of the Country or be otherwise employed and provided for: 5thly Let each agent appointed by the General agent be required to keep a strict acct of all his transactions, – of all monies recieved [sic] and paid out, of the numbers and the names of slaves brought into our lines under his auspices, of the plantations visited, and of everything properly connected with the prosecution of his work, and let him be required to make full reports of his proceedings – at least, once a fortnight to the General Agent.

6th Also, Let the General Agt be required to keep a strict acct of all his transactions with his agts and report to your Excellency or to an officer designated by you to receive such reports. 7th Let the General Agt be paid a salary sufficient to enable him to employ a competant [sic] Clerk, and let him be stationed at Washington – or at some other Point where he can most readily receive communications from and send communications to his Agents: The General Agt should also have a kind of roving Commission within our lines, so that he may have a more direct and effective oversight of the whole work and thus ensure activity and faithfulness on the part of his agents-

This is but an imperfect outline of the plan – but I think it enough to give your Excellency an Idea of how the desirable work shall be executed.10

Douglass also wrote Mr. Lincoln a personal note on the same day – this one requesting a discharge from the Army for his ailing son Charles. “Now, Mr. President – I hope I shall not presume to[o] much upon your kindness – but I have a very great favor to ask. It is not that you will appointed me General Agent to carry out the Plan now proposed – though I would not shrink from that duty – but it is, that you will cause my son Charles R Douglass. 1stSergeant of Company I – 5th Massachusetts dis-mounted cavalry – now stationed at ‘Point Lookout’ to be dis-charged – He is now sick – He was the first colored volunteer from the State of New York – having enlisted with his Older Brother in the Mass – 54th partly to encourage enlistments – he was but 18. When he enlisted – and has been in the service 18. Months. If your Excellency can confer this favor – you will lay me under many obligations[.]”11 The President complied.

Frederick Douglass wavered on his support of Mr. Lincoln’s reelection in 1864 but after the August meeting, he came out strongly for President Lincoln’s reelection in mid-September. Historian James M. McPherson wrote: “While there was, or seemed to be, the slightest possibility of securing the nomination and election of a man to the Presidency of more decided anti-slavery convictions and a firmer faith in the immediate necessity and practicability of justice and equality for all men, than have been exhibited in the policy of the present administration, I, like many other radical men, freely criticized, in private and in public, the actions and utterances of Mr. Lincoln, and withheld from him my support. That possibility is now no longer conceivable; it is now plain that this country is to be governed or misgoverned during the next four years, either by the Republican Party represented in the person of Abraham Lincoln, or by the (miscalled) Democratic Party, represented by George B. McClellan. With this alternative clearly before us, all hesitation ought to cease, and every man who wishes well to the slave and to the country should at once rally with all the warmth and earnestness of his nature to the support of Abraham Lincoln.”12

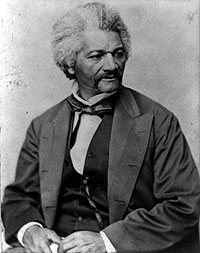

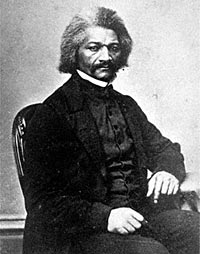

Born Frederick Bailey in 1818, Douglass was never sure of his father although it seems certain that he was white and was possibly was his owner, Thomas Auld. Douglass had little contact with his mother and was brought up by his grandmother until the age of seven when he was turned over to the main plantation house on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. His early life was a difficult one in which he was somewhat more privileged than the average slave child, associating with white playmates (through whose association he learned to read and play the violin), but also more stressful because he was separated totally from his family and moved from place to place – spending a portion of his time in Baltimore before he was shipped back to the Eastern Shore. There, an abortive escape attempt and fight led to his return to slave status in Baltimore as ship’s caulker.

Although Douglass had been promised eventual freedom, a dispute over his pay with his master led to his decision to escape North, eventually to New Bedford, Massachusetts where he changed his name to avoid return to slavery. Before he escaped, he had fallen in love with a free but illiterate black woman, Anna Murray, a domestic five years his senior. She followed him North and they married in New York City before continuing on. They eventually had five children – two daughters and three boys. They remained married until Anna’s death in 1882 though Anna never learned to read and never really participated in his political activities.

At a church meeting in New Bedford in 1839, Douglass made his first speech – denouncing colonization and deportation of black slaves. He remained a fervent foe of such schemes and a proponent of integration for the rest of his life. He soon fell into the circle of William Lloyd Garrison and the American Anti-Slavery Society. Douglass eventually broke with Garrison and the Society over their opposition to any kind of political involvement and their condemnation of the Constitution. Like Mr. Lincoln, Douglass felt the Constitution should be a protection against, rather than a sanction for slavery. For years, first under the auspices of the Society and then under his own sponsorship, Douglass toured the U.S., Ireland, Scotland and England speaking against slavery.

Later, he formed his own newspaper, the North Star (later Frederick Douglass’ Paper) and moved his family to Rochester, New York. (In the mid-1840s, Douglas’s freedom had been purchased by white friends from his former master in order to guarantee his freedom of movement.) In his paper in 1851, he wrote that the Constitution “construed in the light of well established rules of legal interpretation, might be made consistent…with the noble purposes avowed in his preamble” and called for the Constitution to be “wielded in behalf of emancipation.”13

Later, in perhaps his famous “Fifth of July Speech,” Douglass declared: “Fellow-citizens! there is no matter in respect to which, the people of the North have allowed themselves to be so ruinously imposed upon, as that of the pro-slavery character of the Constitution. In that instrument I hold there is no warrant, license, nor sanction of the hateful thing; but, interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the constitution is a GLORIOUS LIBERTY DOCUMENT.”14

Frederick Douglass never wanted to be confined to a particular role which white Northerners might want to limit him. He wasn’t content to a token Black. He believed in integration and he lived his beliefs – frequently with great courage. Douglass was not inclined to sugarcoat his message or to be obsequious to white abolitionists who wanted to keep him in his place. Furthermore, his working relationships were frequently better with white women abolitionists than with their male counterparts. Unlike Mr. Lincoln for whom male friendships were easiest (particularly with a jealous wife), female friendships (with intellectually stimulating and strong women) were easiest for Douglass (whose wife appears to have been much more tolerant than most women would have been considering some visitors came to live with them for months or years). Douglass worked frequently with representatives of the women’s suffrage movement.

Douglass was an early backer of William H. Seward and the Republican Party and strong opponent of Stephen Douglass, about whom he said after his death, “No man of his time has done more than he to intensify hatred of the negro.”15 Douglass strongly backed Mr. Lincoln’s election in 1860 over Stephen Douglas but was highly critical of the Lincoln Administration’s tentative approach to emancipation. His respect for Mr. Lincoln grew slowly through the Civil War – after Mr. Lincoln fulfilled two of Douglass’s objectives – emancipation and black recruitment – although he held Mr. Lincoln to high standards and said in a Rochester speech in 1862 that Americans had “a right to hold Abraham Lincoln sternly responsible for any disaster or failure attending the suppression of this rebellion.”16

Like Mr. Lincoln, he had impoverished childhood with considerable trauma, much abandonment, and little formal education. Unlike Mr. Lincoln who avoided most references to his childhood, Douglass made his childhood experiences with slavery into the centerpiece of his speaking and writing. Like Mr. Lincoln, Douglass operated somewhat above his “birth” class but still acted as a representative of that class with whom he was somewhat out of touch. Like Mr. Lincoln, he was tall, but he carried himself with a more regal and dignified bearing. Like Mr. Lincoln, he was proud of his physical strength and his erstwhile physical labors. Like Mr. Lincoln, he was frequently disappointed in the pursuit of office.

Like Mr. Lincoln, Douglass had strong early experiences with the church, but his chagrin with the refusal of white churches to denounce slavery led to his detachment from his Methodist roots. Like Mr. Lincoln, he understood that the North was far from blameless on issues of race and slavery. In one early speech, Douglass said: “Prejudice against color is stronger north than south; it hangs around my neck like a heavy weight.”17

Like Mr. Lincoln, Douglass had a high opinion of his own abilities – which he tended to deprecate in public comments. Like Mr. Lincoln, he was an accomplished mimic – but unlike Mr. Lincoln, most of his mimicry was used in speeches rather than story-telling.

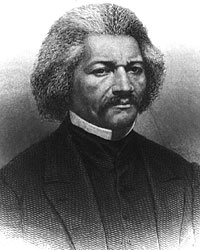

Historian David W. Blight wrote: “In May 1861 Douglass gave his readers a classic jeremiad wrapped in apocalyptic language. ‘We have sown the wind, only to reap the whirlwind,’ he changed. ‘The Republic has put one end of the chain upon the ankle of the bondman, and the other end about its own neck.’ A chosen but sinful people were about to reap the harvest of their own iniquity: ‘The land is now to weep and howl, amid ten thousand desolations brought upon it by the sins of two centuries….Could we write as with lightning, and speak as with the voice of thunder, we should…cry to the nation, Repent, Break Every Yoke, let the Oppressed Go Free for Herein alone is deliverance and safety!’ But it was not too late, Douglass claimed, if the slaves’ ‘cry of vengeance’ could be merged with the cry to save the Union. The moment of truth in the nation’s life had been reached.”18

Douglas campaigned tirelessly for emancipation. He wrote in his newspaper that “The very stomach of this rebellion is the negro in the condition of a slave. Arrest that hoe in the hands of the negro, and you smite rebellion in the very seat of its life…The negro is the key of the situation – the pivot upon which the whole rebellion turns…Teach the rebels and traitors that the price they are to pay for the attempt to abolish this Government must be the abolition of slavery…Henceforth let the war cry be down with treason, and down with slavery, the cause of treason.”19

Historian David W. Blight wrote: “In 1862-63, the prospect of emancipation gave a new purpose to the Civil War and a new meaning to American history. For the slaves and for abolitionists, both black and white, emancipation was initially something more easily felt than explained. For Frederick Douglass, the former fugitive slave turned orator-editor and the leading black spokesman in America, a most important moment had been reached in a long struggle. One year into the conflict, Douglass spoke of the inexorable way emancipation had become the war’s central question: ‘It is really wonderful…how all efforts to evade, postpone, and prevent its coming, have been mocked and defied by the stupendous sweep of event[t]s.’ Douglas searched for ways to understand and affect the turn of events. In large measure, his wartime thought reflects a spiritual interpretation of the war that fits squarely into several intellectual and theological traditions: millennialism, apocalypticism, civil religion, the providential view of history, and jeremiad.”20

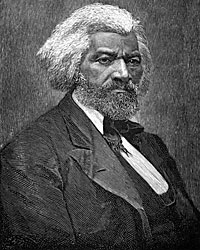

In his 1876 “Freedmen’s Monument” speech, Douglass said: “Can any colored man, or any white man friendly to the freedom of all men, ever forget the night which followed the first day of January 1863, when the world was to see if Abraham Lincoln would prove to be as good as his word? I shall never forget that memorable night, when in a distant city I waited and watched at a public meeting, with three thousand others not less anxious than myself, for the word of deliverance which we have heard read today. Nor shall I ever forget the outburst of joy and thanksgiving that rent the air when the lightning brought to us the emancipation proclamation. In that happy hour we forgot all delay, and forgot all tardiness, forgot that the president had bribed the rebels to lay down their arms by a promise to withhold the bolt which would smite the slave system with destruction; and we were thenceforward willing to allow the president all the latitude of time, phraseology, and every honorable device that statesmanship might require for the achievement of a great and beneficent measure of liberty and progress.”21

Giving a speech in New York, Douglas said “The change in the attitude of the Government is vast and startling…For more than 60 years the Federal Government has been little better than a stupendous engine of Slavery and oppression, through which Slavery has ruled us, with a rod of iron.”22 Lincoln scholar Harold Holzer wrote: “Frederick Douglass, who more than any leader of the day understood the restraints on Lincoln and his heroic response in spite of them, knew the document would never stand the test of time as literature, line by line. But Douglass read between the lines. Even though the proclamation had been inspired. Douglas said, by ‘the low motive of military necessity,’ he realized at once that it was ‘a little more than it purported.’ As he put it, ‘I saw that its moral power would extend much further.’ In that dry document Frederick Douglass sensed a ‘spirit and power far beyond its letter.'”23

After Mr. Lincoln’s death, Douglass continued the fight for black equality – especially for black suffrage. He remained a strong supporter of the Republican Party until his death in 1892 – largely because of his antipathy to Democratic involvement in protecting slavery. He moved to Washington after his Rochester house burned down in 1872. Under Grant, he was appointed President of the Freedmen’s Bank, a banking institution which was destined for failure before Douglass arrived. Under President Rutherford Hayes, he was appointed U.S. Marshall for the District of Columbia; under President James Garfield, he was recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia, and under President Benjamin Harrison, he was U.S. Ambassador to the District of Columbia.

Douglass remained a great believer that political and economic equality would solve the problems of freed blacks. Shortly after Mr. Lincoln’s death, he expressed “doubts about these Freedmen’s Societies. They may be the necessity of the hour…but I fear everything looking to their permanence. The negro needs justice more than pity, liberty more than old clothes.”24

In his memoirs, Douglass wrote: “I have often said elsewhere what I wish to repeat here, that Mr. Lincoln was not only a great president, but a great man – too great to be small in anything. In his company I was never in any way reminded of my humble origin, or of my unpopular color. While I am, as it may seem, bragging of the kind consideration which I have reason to believe that Mr. Lincoln entertained towards me, I may mention one thing more. At the door of my friend John A. Gray, where I was stopping in Washington, I found one afternoon the carriage of Secretary Dole, and a messenger from President Lincoln with an invitation for me to take tea with him at the Soldiers Home, where he then passed his nights, riding out after the business of the day was over at the Executive Mansion. Unfortunately I had an engagement to speak that evening, and having made it one of the rules of my conduct in life never to break an engagement if possible to keep it, I felt obliged to decline the honor. I have often regretted that I did not make this an exception to my general rule. Could I have known that no such opportunity could come to me again, I should have justified myself in disappointing a large audience for the sake of such a visit with Abraham Lincoln.”25

Political scientist Lucas Morel analyzed the 1876 speech in which Douglass described Mr. Lincoln as the white man’s president. Douglass said to “my white fellow citizens” that “First, midst, and last, you and yours were the objects of his deepest affection and his most earnest solicitude. You are the children of Abraham Lincoln. We are at best only his stepchildren; children by adoption, children by force of circumstances and necessity.” Douglass noted that it was necessary for Mr. Lincoln to be primarily the white man’s president in order to eliminate slavery. Morel noted that “to achieve either union or emancipation, he needed the support of ‘his loyal fellow-countrymen.’ This leads to the climax of the [Douglass] speech: ‘Had he put the abolition of slavery before the salvation of the Union, he would have inevitably driven from him a powerful class of the American people and rendered resistance to rebellion impossible.”26

Douglas’s respect for Mr. Lincoln’s leadership was deeply felt. Morel wrote: “Just two years after his 1876 oration, Douglass spoke at Union Square, New York, to the Lincoln Post of the Grand Army of the Republic. There he called Lincoln ‘the best man, truest patriot, and wisest statesman of his time and country.’ Given the host and venue, this comes as no surprise. But Douglass repeated this high praise of Lincoln five years alter in a fiery speech titled ‘The United States Cannot Remain Half-Slave and Half Free.’ After observing that Lincoln’s name ‘should never be spoken but with reverence, gratitude, and affection,’ Douglass called him ‘the greatest statesman that ever presided over the destinies of this Republic.”27

Footnotes

- William S. McFeely, Frederick Douglass, p. 229.

- Frederick Douglas, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, p. 350-351.

- David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War, p. 183-184.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from William P. Dole to Abraham Lincoln, August 18, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 499-501 (Letter to Charles D. Robinson, August 17, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 507 (Letter from Frederick Douglass to Abraham Lincoln, August 19, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter of Frederick Douglass to President Lincoln, August 29, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter of Frederick Douglass to President Lincoln, August 29, 1864).

- Unpublished manuscript, National Archives, (Letter from Frederick Douglass to Abraham Lincoln, August 29, 1864).

- James M. McPherson, The Negro’s Civil War, p. 310.

- William S. McFeely, Frederick Douglass, p. 169.

- William S. McFeely, Frederick Douglass, p. 172-173.

- William S. McFeely, Frederick Douglass, p. 187.

- William S. McFeely, Frederick Douglass, p. 214.

- William S. McFeely, Frederick Douglass, p. 94.

- Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh, editor, The Price of Freedom: Slaver and the Civil War, Volume I, p. 18-19 (David W. Blight, “Frederick Douglass and the American Apocalypse”).

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 21.

- Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh, editor, The Price of Freedom: Slaver and the Civil War, Volume I, p. 5-6 (David W. Blight, “Frederick Douglass and the American Apocalypse”).

- Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, p. 484.

- Susan-Mary Grant and Brian Holden Reid, editor, The American Civil War: Explorations and Reconsiderations, p. 224 (Robert Cook, “The Fight for Black suffrage in the War of the Rebellion”).

- Harold Holzer, Lincoln Seen and Heard, p. 189.

- William S. McFeely, Frederick Douglass, p. 241.

- Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, p. 350.

- Charles M. Hubbard, editor, Lincoln Reshapes the Presidency, p. 145 (Lucas E. Morel, “Lincoln’s Legacy of Political Transcendance”).

- Charles M. Hubbard, editor, Lincoln Reshapes the Presidency, p. 150 (Lucas E. Morel, “Lincoln’s Legacy of Political Transcendance”).

- David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, p. 15-16.

- David W. Blight, Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory, p. 17.