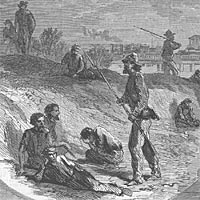

“Southern whites were accustomed to looking upon black men as slaves, and it was hard for them to accept the idea that black soldiers were free men who must be treated according to the laws of war, not the laws of slavery,” wrote historian James M. McPherson. “In some instances, rebel officers or soldiers refused to take black prisoners or murdered them after they had surrendered.”1 Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “The official Confederate position was one of extreme harshness modified by a prudent fear of Northern retaliation. Jefferson Davis had lost no time after the emancipation in telling the Confederate Congress that unless it otherwise directed, he would order all Union officers captured at the head of colored troops to be delivered to the States to be dealt with under their laws for punishing those who excited servile insurrection. This implied a death penalty. Congress showed more restraint. By joint resolution it declared that such officers should be put to death or ‘otherwise punished’ at the discretion of a military court. Mere privates were to be sent back to their States of origin.”2

The Confederate Congress passed legislation which said: “All negroes and mulattoes who shall be engaged in war, or be taken in arms against the Confederate States, or shall give aid or comfort to the enemies of the Confederate States, shall, where captured in the Confederate States, be delivered to authorities of the State or States in which they shall be captured, to be dealt with according to such present or future laws of such State or States.” The law also said that white Union officers “Who shall voluntarily use negroes or mulattoes in any military enterprise, attack or conflict, in such service, shall be deemed as inciting servile insurrection, and shall, if captured, be put to death, or to be otherwise punished at the discretion of the court.”3

In December 1862, Confederate President Jefferson Davis issued a proclamation which anticipated the use of former slaves as Union soldiers. Davis declared “That all negro slaves captured in arms be at once delivered over to the executive authorities, of the respective Stats to which they belong, and to be dealt with according to the laws of said States.” Davis went to declare: “That the like orders be executed in all cases with respect to all commissioned officers of the United States when found serving in company with said slaves in insurrection against the authorities of the different States of this Confederacy.”4

Contemporary Lincoln biographer Josiah G. Holland wrote: “The government was pledged to the protection of its black soldiers. The President felt that the matter involved many difficulties, for the government was not always able to protect them. When these soldiers were shown no quarter in battle, or when, as prisoners, they were skilled or enslaved by the infuriated and unscrupulous foe, he who could not prevent his white soldiers from starving to death in rebel prisons, could hardly protect the colored soldiers from the indignities which rebel policy and rebel spite inflicted upon them. But he did what he could.5 Holland cited the proclamation which President Lincoln issued on July 30, 1863:

It is the duty of every government to give protection to its citizens, of whatever class, color, or condition, and especially to those who are duly organized as soldiers in the public service. The law of nations and the usages and customs of war as carried on by civilized powers, permit no distinction as to color in the treatment of prisoners of war as public enemies. To sell or enslave any captured person, on account of his color, and for no offence against the laws of war, is a relapse into barbarism and a crime against the civilization of the age.

The government of the United States will give the same protection to all its soldiers, and if the enemy shall sell or enslave anyone because of his color, the offense shall be punished by retaliation upon the enemy’s prisoners in our possession.

It is therefore ordered that for every soldier of the United States killed in violation of the laws of war, a rebel soldier shall be executed; and for every one enslaved by the enemy or sold into slavery, a rebel soldier shall be placed at hard labor on the public works and continued at such labor until the other shall be released and received the treatment due a prisoner of war.6

Even in Washington, D.C., there was much prejudice against black recruits. Volunteering by contrabands and free blacks was a dangerous business – long before they faced enemy fire, wrote historian Margaret Leech. Bigotry threatened to lead to race violence in Washington. “When the companies [of black recruits] were at last mustered in [May 1863], they were hurriedly taken from Washington to Analostan Island, opposite Georgetown. There, out of sight, they were clothed in the army blue. Their removal was a discouragement to the white recruiting officers, who wanted to use them to stimulate enthusiasm and reassure the doubtful. These officers were not permitted, under penalty of arrest, to visit Analostan Island. One of them said that the President himself did not know where the colored soldiers were encamped, but had been driving around Washington with Mrs. Lincoln, trying to find them.”7

Historian Leech wrote that recruitment in 1863 “made slow progress. The available number of able-bodied contrabands was reduced by the fact that many were already employed, as laborers and teamsters, by the Government. The city Negroes, mistrustful, hung back. At meeting after meeting in the colored churches, white speakers and black worked to whip up enthusiasm. At the first of these meetings, Massachusetts soldiers stood on guard at the church doors and in the aisles. In the capital, a Negro recruit not only feared the vengeance of the Confederates if he should be taken prisoner; he was in immediate danger at the hands of his white comrades and the secessionist bullies who loitered in the streets.”8

Historian Allan Nevins wrote.: “As it was in the Mississippi Valley that most Negro recruiting was done, there the Confederates faced the most acute problem in dealing with colored soldiers. They knew that they were on precarious ground. The Tennessee legislature in the first autumn of the war had empowered Governor Harris to enlist free Negroes for military service. [Governor Thomas Overton] Moore of Louisiana had paraded 1,400 Negro militia, and various Southern officers had used slave labor for fortifications. Nevertheless, so cultivated a gentleman as E. Kirby-Smith, West Point 1845, issued brutal orders. When Richard Taylor’s troops first captured Negroes in arms, Kirby-Smith rebuked him for not killing them on the field. Refusal to give quarter would offer the simplest (he did not need to add the cruelest) way out of a painful dilemma, for if the South executed Negro soldiers by formal order, the North would assuredly execute as many Southern soldiers with the same formality. Secret murder was the only safe method. Secretary Seddon was guilty of the same cowardly type of brutality. Recommending to Kirby-Smith that Negro soldiers be treated kindly and returned to their masters, he advised that their white officers be dealt with ‘red-handed’ on the field or immediately afterward.”9

Nevins wrote that rumors of atrocities were more prevalent than hard facts: “It was in the West, too, that executions and denials of quarter were most frequently reported: the murder of twenty Negro teamsters in Union service near Murfreesboro, the public hanging of three Negroes at Holly Springs and so on. How much truth the atrocity stories contain it is impossible to say…”10 In late May 1863, President Lincoln received a set of resolutions from the National Freedmen’s Relief Association:

Whereas it is a matter of public information that Jefferson Davis, styled President of the so called Confederate States has issued a proclamation relative to the officers and members of colored regiments, as cruel and anti Christian in spirit as it is repugnant to all rules of civilized warfare:

Whereas it continues to be represented that the public journals and by private letters until there can be no doubt of the fact, that federal Officers of the Army and Navy, having asked and obtained the aid of colored men as scout, spies and laborers, especially in securing supplies and valuable contraband property, then abandon them to the savage mercies of their masters, and to death at their hands:

Whereas Colored men who have escaped from slavery under rebel masters and are legally free according to the proclamation of the President of January 1st, are taken and sold into slavery for jail fees, in the border states, especially in Kentucky, in positive violation of the spirit if not the letter of said Proclamation, therefore:Resolved, That we the undersigned committee of the National Freedman’s Association, while we have witnessed with the liveliest interest the many benificent measures the Government has instituted in behalf of this unfortunate race, we would most respectfully and earnestly call the attention of Your Excellency and of the public authorities to this important and humane subject. That some proper and so far as feasible, sufficient means be taken to place the officers and men of colored regiments in the same relations as those of white regiments. That common humanity, enlightened policy and our national good name demand this.

Resolved That we urgently request that prompt and adequate orders be given our officers of the Army and Navy, not only not to repulse, but in all cases to call to their aid and fully protect all colored people in the same spirit and manner that they would whites, recognizing the great truth that the rights of justice and law belong to the man and not to his outward circumstances nor to his color.

Resolved That national honor and interest are alike pledged to the colored man and before the world, to the faithful enforcement of the President’s Proclamation throughout the states and territories up to the full measure of the final freedom of those in whose behalf it was put forth. Less than this would be a fearful exhibition of national bad faith and justly calculated to provoke the rightious [sic] indignation of all good men and the displeasure of the Sovereign Ruler of the world.

Resolved That we hail with delight the benevolent action of the Government and its firm exhibition of moral courage in the face and in spite of the obstinate p[r]ejudice of the age, also the encouraging advance of public sentiment and their combined willingness practically to acknowlege [sic] that all men are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights, and among them are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

Resolved That if we…, as a nation or as individuals would invoke the favor of Almighty God and be shielded and delivered from the fearful calamities of his displeasure, we must ourselves do unto others as we would have them do unto us, love mercy & practice justice.11

Massachusetts Governor John Andrew was an outspoken proponent of the recruitment of black soldiers and advocate for their rights once recruited. In mid-June 1863, he wrote President Lincoln: “I most respectfully and earnestly present to your attention the annexed original of a communication received by me on a subject of the utmost importance, and I invoke for those immediately concerned therein the amplest protection which a public and unequivocal Proclamation of the purpose of the Executive Government of the United States may be able to impart. The publication of a proper avowal of the Government’s purpose to punish promptly, unhesitatingly, and in every instance, according to the rights of war, every infringement of the rights of the class of soldiers to which this memorial refers, will be a powerful shield for their defence. I doubt not the purpose and will of the President; but the moral influence of its clear avowal remains yet to be secured.”12

The next day, Governor Andrew wrote President Lincoln: “I inclose to you a memorial concerning Federal protection for colored troops, – and also a letter addressed by me to the President in support of it. May I ask you to present them to the President and to urge the subject upon his attention? I am sure that your interest in the prayer of the memorialists, – and aside from their own very high character, – will cause you to press the matter until some authoritative proclamation of the President’s purpose to protect our troops is gained.”13 Nearly six weeks later, the mother a black soldier in the 54thMassachusetts Regiment admonished President Lincoln to take proper care of soldiers like her son:

“My good friend says I must write to you and she will send it[.] My son went in the 54th regiment. I am a colored woman and my son was strong and able as any to fight for his country and the colored people have as much to fight for as any[.] My father was a Slave and escaped from Louisiana before I was born more forty years agone. I have but poor edication [sic] but I never went to schol [sic], but I know just as well as any what is right between man and man. Now I know it is right that a colored man should go and fight for his country, and so ought to a white man. I know that a colored man ought to run no greater risques than a white, his pay is no greater his obligation to fight is the same. So why should not our enemies be compelled to treat him the same, Made to do it.

My son fought at Fort Wagoner but thank God he was not taken prisoner, as many were I thought of this thing before I let my boy go but then they said Mr. Lincoln will never let them sell our colored soldiers for slaves, if they do he will get them back quck [sic] he will rettallyate [sic] and stop it. Now Mr Lincoln don’t you think you o[u]ght to stop this thing and make them do the same by the colored men[.] They have lived idleness all their lives on stolen labor and made savages of the colored people, but they now are so furious because they are proving themselves to be men, such as have come away and got edication [sic]. It must not be so. You must put the rebels to work in State prisons to making shoes and things, if they sell our colored soldiers, till they let them go. And give their wounded the same treatment. It would seem cruel, but their no other way, and a just man must do hard things sometimes, that shew him to be a great man. They tell me some do [think] you will take back the Proclamation, don’t do it. When you are dead and in Heaven, in a thousand that action of yours will make the Angels sing your praises I know it. Ought one man to own another, law for or not, who made the law, surely the poor slave did not. So it is wicked, and a horrible Outrage, there is no sense in it, because a man has lived by robbing all his life and his father before him, should he complain because the stolen things founds on him are taken. Robbing the colored people of their labor is but a small part of the robbery their souls are almost taken, they are made bruits of often. You know all about this almost taken, they are made bruits of often. You know all about this

Will you see that the colored men fighting now, are fairly treated. You ought to do this, and do it at once, Not let the thing run along meet it quickly and manfully, and stop this, mean cowardly cruelty. We poor oppressed ones, appeal to you, and fair play.14

According to historian James M. McPherson: “Black prisoners who survived the initial rage of their captors sometimes found themselves returned as slaves to their old masters or, occasionally, sold to a new one. While awaiting this fate, they were often placed at hard labor on Confederate fortifications.”15However, an even worse fate awaited soldiers who attempted to surrender after an Confederates led by General Nathan Bedford Forrest on Fort Pillow in Tennessee on April 12, 1864. Major Lionel F. Booth commanded the black Union soldiers at Fort Pillow. The garrison’s 570 soldiers were half white and half black. Noah Andre Trudeau wrote in Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War that when the Confederate attacked, “Panic spread among the Union troops, with blacks and whites each later blaming the other for breaking first. What is clear is that while a few Federals stood their ground, most threw down their guns, some to run for the presumed safety of the bluff, others to raise their hands in surrender. No one had lowered the U.S. flag.”16Although Union soldiers attempted to surrender, many were instead killed. According to Trudeau, “What came next was a massacre, pure and simple. Corporal William A. Dickey, 13th Tennessee Cavalry, ran from the wall when Forest’s men breasted it. ‘The rebels followed closely,’ he recalled, ‘shooting down all who came in the way, white and black….One rebel came to me and took my percussion caps, saying he had been killing negroes so fast that his own had been exhausted; he added that he was going to shot some more.'”17

Confederate General Forrest himself prepared a report which stated “A demand was made for the surrender, which was refused. The victory was complete, and the loss of the enemy will never be known from the fact that large numbers ran into the river and were shot and drowned. The force was composed of about 500 negroes and 200 white soldiers (Tennessee Tories). The river was dyed with the blood of the slaughtered for 200 yards. There was in the fort a large number of citizens who had fled there to escape the conscript law.”18

According to Lincoln chronicler Ronald C. White, Jr., “Lincoln was besieged with calls for retribution.”19 The Fort Pillow massacre horrified and alarmed whites and blacks in the North. Historian T. Harry Williams wrote: “The newspapers supplied the public with sensational and, in some respects, exaggerated accounts. The great illustrated weeklies dramatized the scenes at Pillow with vivid sketches. Immediately the Jacobins set up a clamor for measures of retaliation upon Confederate prisoners. They charged that Abraham Lincoln was the real murderer of the Negro garrison. If he had threatened reprisals when the Confederacy first announced that it would not grant colored soldiers the protection of the laws of war, the Fort Pillow tragedy would never have occurred.”20

Journalist Noah Brooks, who frequently visited the White House, wrote: “The black-flag business seems to have been fairly begun by the rebel savages to whom For Pillow surrendered. That due revenge will be taken for that massacre, with or without orders, is a foregone conclusion. Man for man, blood for blood, the terrible reckoning will be taken. Revenge – retaliation – is unchristian to the last degree, that is very true; but war is not a Christian institution in any point of view, and many of its necessities are as heathenish as the Tartar conqueror’s monument of skulls.”21 The incident evoked a strong reaction among both black and white northerners. Theodore Hodgkins, a black New Yorker, wrote Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton:

Some Sixty or Seventy thousand of my down trodden and despised brethren now wear the uniform of the United States and are bearing the gun and sword in protecting the life of this once great nation[.] with this in view I am emboldened to address a few words to you in their behalf if not in behalf of the government itself. Jeff Davis issued a threat that black men fighting for the U.S. should not be treated as prisoners of war and the President issued a proclamation threatening retaliation. Since then black soldiers have been murdered again and again yet where is there an instance of retaliation. To be sure there has been a sort of secrecy about many of these slaughters of colored troops that prevented an official declaration to be made but there is now an open and bold murder, an act following the proclaimed threat made in cold blood gives the government an opportunity to show the world whether the rebels or the U.S. have the strongest power. If the murder of the colored troops at Fort Pillow is not followed by prompt action on the part of our government. It may as well disband all its colored troops for no soldiers whom the government will not protect can be depended upon Now Sir if you will permit a colored man to give not exactly advice to your excellency but the expression of his fellow colored men so as to give them heart and courage to believe in their goverment [sic] you can do so by a prompt retaliation. Let the same no. of rebel soldiers, privates and officers be selected from those now in confinement as prisoners of war captured at the west and let them be surrounded by two or three regiments of colored troops who may be allowed to open fire upon them in squads of 50 or 100, with howitzers loaded with grape. The whole civilized world will approve of this necessary military execution and the rebels will learn that the U.S. Govt. is not to be trifled with and the black men will feel not a spirit of revenge for have they not often taken the rebels prisoners even their old masters without indulging in a fiendish spirit of revenge or exultation. Do this sir promptly and without notice to the rebels at Richmond when the execution has been made then an official declaration or explanation may be made. If the threat is made first or notice given to the rebels they will set apart the same no. for execution. Even that mild copperhead Reverdy Johnston [sic] avowed in a speech in the Senate that this govt. could only be satisfied with man for man as an act of retaliation. This request or suggestion is not made in a spirit of vindicativeness [sic] but simply in the interest of my poor suffering confiding fellow negros [sic] who are even now assembling at Annapolis [Md.] and other points to reinforce the army of the Union. Act first in this matter[,] afterward explain or threaten the act tells the threat or demand is regarded as idle.22

“This matter of retaliation was brought up during Mr. Lincoln’s speech at the Baltimore Fair, wrote biographer Josiah G. Holland. “He had just heard the rumor of the massacre of black soldiers and white officers at Fort Pillow. His mind was full of the horrible event; and, as his custom was, he spoke of that which interested him most. The public thought the government was not doing its whole duty in this matter. For the measure which put the black man into the war, he declared himself responsible to the American people, the future historian, and, above all, to God; and he declared that the black soldier ought to have, and should have, the same protection given to the white soldier.”23 Speaking at the Sanitary Commission Fair on April 18, President Lincoln said:

“It is not very becoming for one in my position to make speeches at great length; but there is another subject upon which I feel that I ought to say a word. A painful rumor, true I fear, has reached us of the massacre, by the rebel forces, at Fort Pillow, in the West end of Tennessee, on the Mississippi river, of some three hundred colored soldiers and white officers, who had just been overpowered by their assailants. There seems to be some anxiety in the public mind whether the government is doing it’s [sic] duty to the colored soldier, and to the service, at this point. At the beginning of the war, and for some time, the use of colored troops was not contemplated; and how the change of purpose was wrought, I will not now take time to explain. Upon a clear conviction of duty I resolved to turn that element of strength to account; and I am responsible for it to the American people, to the christian world, to history, and on my final account to God. Having determined to use the negro as a soldier, there is no way but to give him all the protection given to any other soldier. The difficulty is not in stating the principle, but in practically applying it. It is a mistake to suppose the government is indiffe[r]ent to this matter, or is not doing the best it can in regard to it. We do not to-day know that a colored soldier, or white officer commanding colored soldiers, has been massacred by the rebels when made a prisoner. We fear it, believe it, I may say, but we do not know it. To take the life of one of their prisoners, on the assumption that they murder ours, when it is short of certainty that they do murder ours, might be too serious, too cruel a mistake. We are having the Fort-Pillow affair thoroughly investigated; and such investigation will probably show conclusively how the truth is. If, after all that has been said, it shall turn out that there has been no massacre at Fort-Pillow, it will be almost safe to say there has been none, and will be none elsewhere. If there has been the massacre of three hundred there, or even the tenth part of three hundred, it will be conclusively proved; and being so proved, the retribution, shall as surely come. It will be matter of grave consideration in what exact course to apply the retribution; but in the suppose case, it must come.24

On May 3, President Lincoln sent a memo to his Cabinet: “It is now quite certain that a large number of our colored soldiers; with their officers, were, by the rebel force, massacred after they had surrendered, at the recent capture of Fort-Pillow. So much is known, though the evidence is not yet quite ready to be laid before me. Meanwhile, I will thank you to prepare, and give me in writing your opinion as to what course, the government should take in the case.”25 Ronald C. White, Jr., observed in Lincoln’s Greatest Speech that President Lincoln “received long and very different replies. Cabinet officers Seward, Chase, Stanton, and Welles argued that Confederate troops equal in number to the Union troops massacred should be held as hostages. They contended that the Southern soldiers should be killed if the Confederate government admitted the massacre. Cabinet officers Usher, Bates, and Blair advocated no retaliation against innocent hostages, but argued for orders to commanders in the field to execute the actual offenders. The responses in the Cabinet mirrored the debate being argued across the nation.”26 The Cabinet replies came in over the four days:

- Attorney General Edward Bates, May 4, 1865:

I foresaw the great probability of such horrid results as those exhibited in the massacre of Fort Pillow (and, as reported, at other places); and that was one of the reasons, why, from the beginning, I was unwilling to employ negro troops, in this war. Not because, in my judgment, there is anything in the mere fact of the employment of such troops, legally or morally wrong, but upon grounds of policy, which seemed to me prudent and wise.

All history teaches us that men, (especially in the excitements of open rebellion and revolutionary violence, when all legal barriers are broken down, and all moral restraints removed[)], are always more swayed by their passions and prejudices, than by reason and judgment – more prone to indulge the fierce passion of revenge, than to practice the mild virtues of prudence, moderation, and justice, the end of which is commonly wisdom and peace.

I knew something of the cherished passions and the educated prejudices of the Southern people, and I could not but fear that our employment of negro troops would add fuel to a flame, already fiercely burning, and thus, excite their evil passions to deeds of horrors, shocking to humanity and to Christian civilization. If they alone were doomed to bear the shame and curse of such barbarity, I might have viewed the subject with less of alarm, content to see them sink under a load of moral infamy, superadded to their political crimes. But I feared that it could not be so. I feared that, the crime once begun, we might be drawn into the vortex, and made, however unwillingly, sharers in their guilt and punishment. That we might feel ourselves, in a manner, constrained to practice the like cruel severities, in just retaliation for the past, and in prudent prevention for the future. What I then foresaw, only in apprehension, is now realized in fact; and we are forced to choose between evils, and in the midst of opposite difficulties, what measures are wisest and best (in view of all the circumstances) to punish past atrocities, and prevent their repetition.

Wiser men than I determined the good policy of employing black soldiers; and I (freely acquiescing in their wisdom and authority) accept the new condition, with all its consequences. Surely it is not for the enemy to dictate to us what kind of troops we shall employ against them. They did not ask our consent to their employment of indian savages, in the far west, and yet, (as I am credibly informed) some of our wounded Missouri soldiers were tomahawked and scalped, by their red troops, on the bloody field of Pea Ridge.

Every belligerent must and will choose for himself, what soldiers he will employ; and having chosen, it is not a debatable question whether he shall protect and (if need be) avenge them. It is a simple duty, the failure to perform which would be a crime and a national dishonor.

Having said this much, in explanation of my position and relations with the subject, I proceed to the precise point suggested by your Excellency, which is, what course should be taken by the government, in relation to the case.

This, it seems to me, presents not a question of law, but questions of prudence and policy only; for, as far as I can judge, the law is clearly with you, to inflict such punishment or exact such retribution for the outrage, as may be, at once, within your power and sanctioned by your wise discretion. The case, however, is so complicated in its relations, and the consequences of your resolution, so important and diversified in themselves, and, possibly, so terrible, in their results, that the utmost care and deliberation, are, it seems to me, necessary to a successful and honorable result.

With these views, I give my opinion, and advise as follows-

1. Adopt no plan of action, and especially, make no threat of vengeance or retaliation, without resolving at the same time, to act it out, to the letter, meeting all its consequences, direct and contingent.

2. Demand of the enemy (through your proper military officer) to know whether he avows the massacre at Fort Pillow, as a governmental act, or disavows it as a personal crime.

3. If he disavow the act, then demand that he surrender to you, the two generals Forrest and [James R.] Chalmers, who commanded the army which took Fort Pillow and perpetrated the attrocities complained of, to be dealt with, at your discretion.

4. If he avow and justify the act, then issue an order directed to all your commanders of armies, and all commanders of separate or detached ports and forts, and to all naval commanders, to the effect, that, whenever any one or more of the army of the enemy which captured fort Pillow and committed the massacre there, shall come within the power of such commander, he, the commander, shall cause instant execution to be done upon all such, whether officers or privates.

5. I would have no compact with the enemy for mutual slaughter – no cartel of blood and murder no stipulation to the effect that [‘]if you murder one of my men, I will murder one of yours’!

Retaliation is not mere justice. It is avowedly Revenge; and is wholly unjustifiable, in law and conscience, unless adopted for the sole purposes of punishing past crime and of giving a salutary and blood saving warning against its repetition. In its very nature it must be discretionary.

I will not say that there is no danger that a desperate enemy, in pretended answer to such a course, may make the closing scenes of this war (already replete with horrors) one disgusting spectacle of blood and fire. If that be the demoniac spirit of our enemies (which God, in his mercy forbid) still, be it so – we, of necessity, must accept the consequences. But upon their souls be the guilt, and upon them be the punishment, both here and hereafter.

The subject is full of difficulties, and we have at best, only a choice of evils. And I pray God that your mind may be so enlightened as to enable you to choose a course of measures, most for the good of our country, and least productive of evil consequences.27

- Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, May 6, 1864

There are two reasons which would prevent me from ordering the execution of prisoners, man for man, in retaliation for the masacre at Fort Pillow.

First: That I do not think the measure would be justified by the rules of civilized warfare even in a contest between alien Enemies.

Second: Because, even if allowable in such a contest, it would not be just in itself or expedient in the present contest.

I shall not be able for want of time to dwell on either of these propositions and have not been able to make any extended research to sustain myself by authority in respect to the first – nor is it necessary, ch: 18, p.445 of Hallecks treatise & authorities there cited being conclusive I will dismiss the consideration of that point therefore by saying that if we have not felt authorized to retaliate on the Indians for the masacre’s of our white citizens or soldiers by the masacre of prisoners taken from them in the fight or to execute them afterwards, why should we take a different course with the Confederates for the masacre of our Soldiers black or white

But in dealing with this or any other business we should aim to be just– Now, I maintain that it would not be just to execute the common soldiers of the Confederate army to retaliate for such enormities as that at Fort Pillow. – I think it can be demonstrated both by the history of the manner in which the rebellion was precipitated and by the course of events during the continuance, that the mass of the people at the South and of the Army have but little share in the guilt and should not be held responsible for its horrors – It would not be just therefore to masacre [sic] or to execute them after capture. – It would not be politic if not just – and I believe it would be playing into of the hands of the rebel chiefs for us to take this course – They see, as we do, how little the hearts of this class of their people are in the war by the numerous desertions which take place from their armies and by the readiness with which they return to their allegiance wherever there is the least assurance of protection– They no doubt hope that if we retaliate by the execution of their common soldiers for their masacres that they can inflame this class of their people & soldiers against the people & cause of the Union. I should therefore direct all measures of retaliation against the class which is alone responsible for this cruel butchery.

And the inclination of my mind is to pursue the actual offenders alone in such cases as the present. – To order the most energetic measures for the capture and the most summary punishment when captured.

The nature of the crime is such as sooner or later to insure the punishment of the offenders– They cannot escape by flying to foreign lands for all civilized nations will aid in bringing them to punishment. A proclamation or order that the guilty individuals are to be hunted down, will have far greater terrors and be far more effectual to prevent the repetition of the crime than the punishment of parties not concerned in that crime – [Illegible] is another Any other course would be a step towards recognizing the authority of the Rebel government – Now, whilst Davis himself by having the actual power to punish Forrest for this crime will make himself a party to it by failing to punish him for it, yet unless we mean to recognize the legal authority of the Rebel Govt. there is no propriety in our visiting upon those not actually responsible for the crime the punishment due alone to its perpetrators.

If it had not have been committed and we could stop it by saying we would execute some prisoners in our hands, that would of course, be proper enough. But when the crime has been committed and the question is whether we shall punish the authors vicariously by shooting prisoners who have not been engaged in it with the certainty that such punishment will lead to the shooting of an equal number of our prisoners in the hands of the enemy, and so on till all are shot on both sides, the question is very different.

We cannot gain by that process– The war will by such proceedings assume a savagery which will perhaps lead to intervention and as we will have committed as much of it as the enemy the intervention will be against us.

On the other hand, the continuance of such atrocities by the confederates will rapidly fix the opinion of the world against them and put them out of the pale of civilized nations – We shall find in this alone far more than compensation for any injury we could possibly suffer – But it would not be in the European or Foreign world alone that they would be damaged – Their own people are not so lost to all sense of shame and decency as not to be effected by outrages like this – It will consolidate opinion against them on the continent of America and must in the end demoralize even their armies.28

- Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, May 6:

In obedience to your direction to prepare and give you in writing my opinion as to what course the Government should take in relation to the Massacre, by the rebels, of our colored soldiers with their white officers, after surrender, at Fort Pillow, I respectfully submit the following views.

All soldiers enlisted and mustered into the service of the Nation should, in my judgment, be placed, in all respects, upon the same footing, without regard to complexion; and this equality, so far as protection is concerned was pledged to the colored soldiers by the Presidents Order of July 30, 1863.

To redeem this pledge it becomes necessary to retaliate the slaughter, in violation of the laws of war, of the officers & men who surrendered at Fort Pillow by the execution of an equal or equivalent number of rebel officers & soldiers.

It does not seem probable that the selection for execution of equal numbers would so surely arrest the perpetration of such atrocities as those of Fort Pillow as would the selection an equivalent number of officers of high rank: for the Slaveholding class, which furnishes such officers, holds but very cheap the lives of the nonslaveholding classes which furnish the privates.

I think, therefore, that among the rebel prisoners of highest rank, now held by the United States, there should be taken a number, equivalent, according to the rules of exchange, to the number of officers & men murdered at Fort Pillow & that notice of the selection should be given by the Lieutenant General to the General Commanding the rebel armies, accompanied by a demand for information whether the Fort Pillow murders are sanctioned by the rebel authorities.

Should an affirmative answer be returned or should it become otherwise manifest that those atrocities will not be disavowed but repeated, then the pledge given by the order of July 30, 1863 should be promptly and decisively redeemed.29

- Secretary of State William H. Seward, May 5, 1864

The enquiry you have submitted to me requires me to assume that a large number of the colored soldiers with their white officers in the United States garrison at Fort Pillow were massacred after they had surrendered to the besieging forces.

I think that justice, humanity and the laws of war, entitled every person who thus surrendered to be regarded and treated as a prisoner of war. Neither the national safety nor the national honor will allow the Government to desist from vindicating this right. But the Government ought to proceed with prudence and frankness as well as with firmness in that vindication. Although the exparte evidence of the commission of the cruelties is deemed satisfactory, I nevertheless think that in so grave a case it is expedient to give the insurgents an opportunity to deny the charge and counteract the testimony if they can.

The insurgents may pretend some plea of provocation or retaliation to offer in justification, or at least in extenuation of the cruelties if they have been committed. It would be better to have that plea offered or waived now than to leave a door open to prevarication about it hereafter. If, after giving a hearing or fair chance for hearing on the subject, it shall then appear that the cruelties complained of were committed, and if it shall also appear that they were committed as is now fully believed without justification or extenuation, the insurgents will be under a manifest obligation to disavow them and give satisfactory pledges that they shall not be repeated hereafter. I would therefore advise that the General commanding the United States forces be instructed to state to the commanding General of the insurgents the following points: – That this Government has learned that a number of United States colored soldiers with their white officers were massacred at the siege of Fort Pillow by the captors of the Fort. That this Government has seen no evidence which authorizes it to believe that the insurgents disavow those massacres. I think all farther questions may be delayed until a reasonable time shall have elapsed for receiving answers to these statements from the commanding General of the insurgents.

I would however give to the army of the United States an earnest of the firmness of this Government in its purpose to vindicate the right of all its members to the protection of the laws of war. To this end, I would direct that insurgent prisoners of war now in military custody equal in number and corresponding in rank to the number of United States soldiers and officers who were massacred at Fort Pillow after having surrendered as prisoners of war, be immediately set apart and held in rigorous confinement, and that notice be given to the commanding General of the insurgents that the disposition which shall ultimately be made of the prisoners so confined will depend upon the answers which shall be given by him to the statements which are mentioned.30

- Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, May 5, 1864

Upon the question propounded to my consideration by you, I have the honor to submit the following opinion:

First: That of the rebel officers now held as prisoners by the United States, there should be selected by lot a number equal to the number of persons ascertained to have been massacred at Fort Pillow, who should be immediately placed in close confinement as hostages, to await such further action as may be determined.

Second: That Generals Forrest and Chalmers, and all officers and men known, or who may hereafter be ascertained to have been concerned in the massacre of Fort Pillow, be excluded by the Presidents Special Order, from the benefit of his amnesty, and also that they by his order be exempted from all privilege of exchange or other rights as prisoners of war, and shall, if they fall into our hands, be subjected to trial, and such punishment as may be awarded for their barbarous and inhuman violation of the laws of war towards the officers and soldiers of the United States at Fort Pillow.

Third: That the rebel authorities at Richmond be notified that the prisoners so selected, are held as hostages, for the delivery up of Generals Forrest and Chalmers and those concerned in the massacre at Fort Pillow, or to answer in their stead, and that in case of their non delivery within a reasonable time, to be specified in the notice, such measures will be taken in reference to the hostages by way of retributory punishment for the massacre at Fort Pillow, as are justified by the laws of civilized warfare.

Fourth: That after the lapse of a reasonable time, for the delivery up of Forrest, Chalmers, and those concerned in the massacre, the President proceed to take against the hostages above selected, such measures as may, under the state of things then existing, be essential for the protection of union soldiers from such savage barbarities as were practised at Fort Pillow, and threatened at other places, and to compel the rebels to observe the laws of civilized warfare in respect to the soldiers and officers in the United States service.

Fifth: That the practise of releasing without exchange or equivalent, rebel prisoners taken in battle, be discontinued, and no such privilege or immunity be extended to rebels, while our prisoners are undergoing ferocious barbarity, or the more horrible death of starvation.

Sixth: That precisely the same rations and treatment, be from henceforth practised in reference to the whole number of rebel officers, remaining in our hands, that are practised against either soldiers or officers in our service, held by the rebels.

My reasons for selecting the officers instead of privates, for retaliatory punishment, are: First, because the rebels have selected white officers of colored regiments, and excluded them from the benefit of the laws of war, for no other reason than that they command special troops, and that having thus discriminated against the officers of the United States service, their officers should be held responsible for the discrimination, and Second, because it is known that a large portion of the privates in the rebel Army are forced there by conscription, and are held in arms by terror, and rigorous punishment from their own officers. The whole weight of retaliatory punishment therefore, should in my opinion be made to fall upon the officers of the rebel army, more especially as they alone are the class whose feelings are at all regarded in the rebel states, or who can have any interest or influence in bringing about more humane conduct on the part of the rebel authorities.

A serious objection against the release of prisoners or war who apply to be enlarged, is that they belong to influential families, who through representatives in Congress, and other influential persons, are enabled to make interest with the government. They are the class who, instead of receiving indulgence, ought, in my opinion, to be made to feel the heaviest burthens of the war brought upon them by their own crimes.31

- Secretary of the Interior John P. Usher, May 6, 1864

I have received your note of the 3d instant. I have the honor in compliance with your directions, to submit, for your consideration, my opinion upon the case therein stated.

The rebel authorities at Richmond will be rightfully considered as responsible for the outrage to which you refer, unless they formally disavow it, and visit condign punishment upon the officers who perpetrated or ordered it.

The General duty of the Government will be admitted by those who recognize its obligation to protect all who are mustered into its military service. Every consideration due to our position in the family of nations – to humanity, to civilization should prompt us, in the existing condition of the country, to maintain an habitual and scrupulous observance of the usages of modern warfare, and to exact it from all who are in arms against us. A more signal violation of those usages has rarely occurred. Submission to it would forfeit our honor and invite similar and perhaps aggrevated [sic] outrages in the future.

What should be the mode and measure of redress, and the time for carrying it into effect?

We are upon the eve of an impending battle. Until the result shall have been known it seems to me to be inexpedient to take any extreme action in the premises. If favorable to our arms we may retaliate as far as the laws of War and humanity will permit. If disastrous, and extreme measures should have been adopted, we may be placed in a position of great embarrassment, and forced to forego our threatened purpose in order to avoid a worse calamity.

I do not think it would be wise to inflict retaliation upon the prisoners now in our hands who were captured before the massacre complained of. Of those who may be thereafter captured, the forces under Forrest’s command, or acting in concert with him, are, in the first instance, the proper subjects of retaliation[.]

Some step should now be taken in that direction. The Colored troops should be satisfied that, it is the unalterable purpose of this government to protect them in good faith, and to its utmost ability.

With this view and to vindicate that great law which secures to the soldier the rights and immunities of War, I am of opinion that the government should set apart for execution, an equal number of prisoners who, since the massacre, have been or may hereafter, from time to time, be captured from Forrest[‘]s Command, designating, in every instance, as far as practicable, officers insted [sic] of privates.32

- Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, May 5, 1864

I have not seen or heard the evidence which has been taken in regard to the massacre of our soldiers at Fort Pillow after they had surrendered. It being an admitted fact, however, that there was such butchery, prompt and decisive measures should be taken to prevent its recurrence. It is difficult to say how this is to be done.

We hear in various ways that the rebels intend to give no quarter to the colored soldiers in the Union ranks, but that an indiscriminate slaughter of them shall take place whenever a victory is obtained by the rebels, as at Fort Pillow. Such a vindictive warfare towards a whole race, will unavoidably provoke retaliation by the race proscribed. The persecuted will become equally unrelenting towards their persecutors and if not checked a war of extermination will be the consequence. No human effort will be wholly able to restrain the barbarous slaughter of the blacks on the one hand and rebels on the other after it shall have been once inaugurated. It must, therefore, be prevented at the outset. If not stopped the consequences will be terribly retributive on those who introduced it, as well as cruel to the negroes.

The government should, therefore, interpose, and spare no exertions to prevent a repetition of the outrage. The officer in command and such others as are known to have participated with him should be held accountable for the murders and punished accordingly. We cannot rely upon the rebel authorities doing this; still it should be required of them and also a disavowal of the barbarous policy. The rebel leaders will hardly assume the responsibility of justifying these murders. In the absence of definite information as to whether the policy of granting no quarter to the colored soldiers in the Union armies is recognized and approved by the rebel authorities, it is advisable to proceed deliberately but decisively. Opportunity should be given to the rebels to disavow and disclaim the massacre at Fort Pillow. This disavowal should be promptly made. In the event of neglect or refusal no remedy presents itself to my mind but that of placing in close custody one or more of the rebel officers to be held accountable, and if necessary, to be punished for this inhumanity. It is the duty of the government to protect its soldiers from butchery when captured, no matter what may be their color, or where their residence. In interposing its authority to shield the negro who surrenders and in striving to restrain the rebels within the limits of civilised warfare, the Union armies, whites as well as blacks may become involved in this merciless conflict, though I trust by a wise, firm and judicious policy such a result may be avoided and a repetition of the massacre at Fort Pillow be prevented.

I would therefore suggest-

1. That the rebel authorities be called upon to avow or disavow the policy of killing the negro soldiers in the Union army after they shall have surrendered.

2. That they be required to bring to punishment the officers in command of the rebel forces at Fort Pillow at the time of the massacre.

3. In the event of refusal to punish the officer who was in command or a disavowal of the policy of killing Union soldiers after they have surrendered, that rebel officers be taken into close custody and held accountable for the conduct of the War by the rebels on humane and civilised principles.

These crude and immature suggestions – unsatisfactory to myself for a question of such grave importance – are submitted without having yet seen the evidence taken by the committee or heard the explanations of the rebels – both of which are necessary – as well as more deliberate reflection before coming to a final conclusion on a subject of such responsibility.33

On May 6, the Cabinet met to read and discuss these suggestions on the eve of the Battle of the Wilderness. Historian Bruce Tap wrote: “Every cabinet official agreed that the Richmond government should first be given the chance to disavow the massacre and to acknowledge the legitimacy of black soldiers. Although a variety of opinions was expressed, two general viewpoints emerged. Seward, Stanton, Chase and Secretary of the Interior John P. Usher favored man-for-man retaliation.”34 Navy Secretary Gideon Welles wrote in his diary:

At the Cabinet-meeting each of the members read his opinion. There had, I think been some concert between Seward and Stanton and probably Chase; that is, they had talked on the subject, although there was not coincidence of views on all respects. Although I was dissatisfied with my own, it was as well as most others.

Between Mr. Bates and Mr. Blair a suggestions came out that met my views better than anything that had previously been offered. It is that the Prsident should by proclamation declare the officers who had command at the massacre outlaws, and require any of our officers who may capture them, to detain them in custody and not exchange them, but hold them to punishment. The thought was not very distinctly enunciated. In a conversation that followed the reading of our papers, I expressed myself favorable to this new suggestion, which relieved the subject of much of the difficulty. It avoid communication with the Rebel authorities. Take the matter in our own hands. We get rid of the barbarity of retaliation.

Stanton fell in with my suggestion, so far as to propose that, should Forrest, or Chalmers, or any officer conspicuously in this butchery be captured, he should be turned over for trial for the murder at For Pillow. I sat beside Chase and mentioned to him some of the advantages of this course, and he said it made a favorable impression. I urged him to say so, for it appeared to me that the President and Seward did not appreciate it.35

President Lincoln drafted instructions for Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton but never completed them. It apparently proved easier to threaten the Confederate government than to put a policy into writing. President Lincoln’s draft read:

Please notify the insurgents, through the proper military channels and forms, that the government of the United States has satisfactory proof of the massacre, by insurgent forces, at Fort-Pillow, on the 12th. and 13th. days of April last, of fully [blank space] white and colored officers and soldiers of the United States, after the latter had ceased resistance, and asked quarter of the former.

That with reference to said massacre, the government of the United States has assigned and set apart by name [blank space] insurgent officers, theretofore, and up to that time, held by said government as prisoners of war.

That, as blood can not restore blood, and government should not act for revenge, any assurance, as nearly perfect as the case admits, given on or before the first day of July next, that there shall be no similar massacre, not any officer or soldier of the United States, whether white or colored, now held, or hereafter captured by the insurgents, shall be treated other than according to the laws of war, will insure the replacing of said [blank space] insurgent officers in the simple condition of prisoners of war.

That the insurgents having refused to exchange, or to give any account or explanation in regard to colored soldiers of the United States captured by them, a number of insurgent prisoners equal to the number of such colored soldiers supposed to have been captured by said insurgents will, from time to time, be assigned and set aside, with reference to such captured colored soldiers, and will, if the insurgents assent, be exchanged for such colored soldiers; but that if no satisfactory attention shall be given to this notice, by said insurgents, on or before the first day of July next, it will be assumed by the government of the United States, that said captured colored troops shall have been murdered, or subjected to Slavery, and that said government will, upon said assumption, take such action as may then appear expedient and just.36

Historian James M. McPherson wrote: “But no record exists that the recommendation was carried out. As Lincoln sadly told Frederick Douglass, ‘if once begun, there was no telling where [retaliation] would end.’ Execution of innocent southern prisoners – or even guilty ones – would produce Confederate retaliation against northern prisoners in a never-ending vicious cycle. In the final analysis, concluded the Union exchange commissioner, these cases ‘can only be effectually reached by a successful prosecution of the war. After all, ‘the rebellion exists on a question connected with the right or power of the South to hold the colored race in slavery; and the South will only yield this right under military compulsion.’ Thus, ‘the loyal people of the United States [must] prosecute this war with all the energy that God has given then.'”37

Meanwhile the leaders of the congressional Committee on the Conduct of the War sought to use the Fort Pillow massacre to exert pressure on the President. According to historian T. Harry Williams, “Assurance of action from Lincoln was all the Jacobin bosses wanted. They sped through both houses of congress a joint resolution directing the Committee to investigate the facts of the affair at Pillow. The Committee eagerly accepted the assignment and designated Wade and Gooch to proceed to the West and collect evidence on the spot. The two inquisitors set out on their mission armed with orders from Stanton instructing the military authorities to furnish them full cooperation. At Cairo, Mound City, For Pillow, Memphis, and elsewhere, they took evidence from seventy-eight witnesses, eighteen of whom had not been present at the Pillow massacre. This list included hospital surgeons who had cared for the wounded survivors, soldiers of the garrison who had escaped unharmed, and people who had visited the fort after the battle.”38

Historian Bruce Tap wrote that the Committee on the Conduct of the War’s “reports on Fort Pillow and returned prisoners were among its more positive achievements. Instead of encouraging jealous rivalries among the army’s leaders and singling out target for blame, these investigations focused on the enemy. Although guilty of some exaggeration and distortion, the committee did uncover significant abuses and atrocities. In the case of Fort Pillow, the judgment of numerous modern historians reinforces this point. Some scholars have criticized the committee for stirring up violent emotions, which helped ensure continuing bitterness during the Reconstruction period, but a case can also be made for the committee’s role in boosting northern morale and resolve.”39

In a deliberate to whip up Northern hostility to the South, the Committee’s report was paired with another report which detailed the conditions under which Union soldiers were kept in Southern prisons . “These reporters were the most expert atrocity-propaganda productions of the war period,” wrote historian T. Harry Williams. “The Fort Pillow narrative was a vivid description of the scenes which took place after Forrest’s vengeful troopers stormed the fort and scattered the frightened garrison. The excesses committed, declared the report, were not the results of momentary passions but of a deliberate policy to discourage the use of Negro soldiers:

The rebels commenced an indiscriminate slaughter, sparing neither age nor sex, white or black, soldier or civilian. The officers and men seemed to vie with each other in the devilish work; men, women, and even children were deliberately shot down, beaten, and hacked with sabres; some of the children not more than ten years old were forced to stand up and face their murderers while being shot; the sick and wounded were butchered without mercy, the rebels even entering the hospital and dragging them out to be shot, or killing them as they lay there unable to offer the least resistance.40

Williams wrote: “The testimony hardly justified this sweeping indictment. A great deal of needless killing of the garrison undoubtedly occurred, but the captain of a Union gunboat in the river near the fort testified that before the battle he had removed all women, children, and sick Negroes to the safety of a nearby island.”41 He added: “The techniques of the conscious propaganda appeared on every page of the two reports. The many sweeping accusations which did not square with the evidence showed a deliberate purpose to twist and distort the facts in order to implant the desired opinions in the mass mind. Using the excuse of grammatical necessity, the Committee ‘dressed up’ the testimony of the illiterate Negroes in the Fort Pillow inquiry, and got results of unusual eloquence.”42

Meanwhile, other pressures were brought to bear on President Lincoln. Just before the Philadelphia Sanitary Fair in mid-June 1864, President Lincoln received an unsigned letter about the Bible and black Soldiers. It came two months after the Fort Pillow Massacre on April 12:

Hagar’s Appeal to Abram-

Look a here! Father Abram; They say you’re Father of the Faithful; but I shan’t believe it, unless you’re Faithful yourself. Don’t you go, and let “Old Sallie Seward,” tempt you to turn us out in the Wilderness “Without a pass”; Nor drive us from your bosom, to sleep our last sleep on yonder bloody “Pillow” without even a rag of a Flag to cover us– Haven’t we served you well, for many years, as “Hewers of Wood (when Wood wasn’t Hughing us) and drawers of Water.”? Why should you desert us now, because Old Sallie don’t like the “Irre press ible Conflict” betwixt big I and little I.

She hasn’t much to boast on herself; Didn’t she go a flirting with King Fairo and ‘Bim lick, over the Waters; and say it was only because she was afeard they would kill you, if she didn’t; (I never believed you told her to do it, tho’ she said you did) Now, I have been Faithful, though I was only a bond woman, and Ishmael has fought your battles when your other brave boy was safe in your tent “out of the Draft.” To be sure you have given us “bread and a bottle of Water” but that won’t save us from death or starvation in the “Wilderness”

Ishmael is your Son though he is “dark complected”, and I think you’ll be mighty mean, if you don’t do something to save him from the “Beasts of that [Nathan Bedford] Forrest” or give us a cure form the Polk powders we are forced to Swallow.

You’d better look out, I can tell you, for if you don’t treat us better, we’ll take possession of the Land of Egypt and give you trouble in Careo Care’o[.] If Ishmael once turns Archer in earnest, remember there’s a Prophet C. that says “His hand shall be against every man,” as well as every man’s hand against he[.] And you’d better take care he don’t turn his arrows against you. It would hurt my feelings dreadful bad, to hear the poor lad crying out in the bush, and dying by inches, after being brot up in Old Abe’s tent, and taught to believe that tho’ he was “Son of the bond woman” he was still to be heir with the “Sons of the Free”

You and Sallie had better have “let us alone” in the back tent than after taking me to your bosom to turn us out doors at Sallie’s bidding. Thank God there are Welles even in the Wilderness and Hunter’s near the Forrest and if you wont hear our prayer the Angel of the Lord is not so deaf.

Now let the Sanitary Fair speak to you, on our behalf; if you don’t like to listen to any other Fair One. She will tell you that, Black and White, it makes no difference to her; She nurses and tends us all – without respect to color or party color– Do you do the same Old Abe and Ishmael and I will be Faithful to the Faithful

Your sorrowful Hagar-

“The voice of One Crying in the Wilderness”

“Prepare ye the way of the Lord

Make his paths straight”43

Other pressures on President Lincoln were more specific. Ronald C. White wrote in Lincoln’s Greatest Speech that the plight of her fellow widows moved the widow of Fort Pillow’s commander, Lionell F. Booth. “It was in the midst of the hue and cry that Mrs. Booth traveled from Fort Pickering at Memphis to Fort Pillow to identify her husband’s body for reburial. When she arrived at the fort, she encountered numerous wives of black soldiers who had come for the same purpose. Mrs. Booth was struck that white women and black women were united in grief at the death of their husbands. But one critical difference prompted her decision to speak to President Lincoln.” Mrs. Booth traveled to Washington and met President Lincoln on May 19 to press the case of the black widows and orphans of soldiers killed at Fort Pillow. “Mrs. Booth explained to Lincoln that marriage, as a legal contract, was not possible for blacks who were slaves. She insisted that these black women were married, no matter what Southern law or custom said. She asked Lincoln to make it possible for the black women to be assured of government pensions just as she would receive a pension for herself and her children.”44

According to White: “We have no record of Lincoln’s words to her, but we do have a record of his actions. On that same day he wrote to Charles Sumner, Republican senator from Massachusetts. Sumner, an ardent abolitionist, had often been critical of Lincoln. Nevertheless, Lincoln thought well of Sumner and now asked the senator to take the initiative in translating Mrs. Booth’s request into law. Lincoln wrote Sumner, ‘She makes a point’ that ‘widows and children in fact, of colored soldiers who fall in our service, be placed in law, the same as if their marriages were legal.’ Lincoln wanted Congress to assure that ‘they can have the benefit of the provisions made the widows & orphans of white soldiers.”45

The legislation was passed on July 2, 1864.

Footnotes

- Josiah G. Holland, Holland’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 464-465.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 357 (July 30. 1863).

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 254.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 253.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 520.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 521.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from National Freedmen’s Relief Association to Abraham Lincoln, May 29, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from John A. Andrew to Abraham Lincoln [With Endorsement by Lincoln]1, June 17, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from John A. Andrew to Charles Sumner, June 18, 1863).

- Ira Berlin, Barbara J. Fields, Steven F. Miler, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, editor, Free at Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom, and the Civil War, p. 450-451 (Letter from Hannah Johnson to Abraham Lincoln, July 31, 1863).

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 794.

- Noah Andre Trudeau, Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War, 1862-1865, p. 166.

- Noah Andre Trudeau, Like Men of War: Black Troops in the Civil War, 1862-1865, p. 166.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 329.

- Ronald C. White, Jr., Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural, p.175.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 343.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 222-223.

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 82.

- Allan Nevins, War for the Union, War Becomes Revolution, 1862-1863, p. 520.

- Joseph T. Wilson, The Black Phalanx: African American Soldiers in the War of Independence, the War of 1812 & the Civil War, p. 318.

- Joseph T. Wilson, The Black Phalanx: African American Soldiers in the War of Independence, the War of 1812 & the Civil War, p. 316.

- Ira Berlin, Barbara J. Fields, Steven F. Miller, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie S. Rowland, editor, Free At Last: A Documentary History of Slavery, Freedom and the Civil War, p. 465-466 (Letter from Theodore Hodkins to Edwin M. Stanton, April 18, 1864).

- Josiah G. Holland, Holland’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 465.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 302-303 (Address at Sanitary Fair, Baltimore, Maryland, April 18, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 328 (May 3, 1864).

- Ronald C. White, Jr., Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural, p. 175-176.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Edward Bates to Abraham Lincoln, May 4, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Montgomery Blair to Abraham Lincoln, May 6, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Salmon P. Chase to Abraham Lincoln, May 6, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from William H. Seward to Abraham Lincoln, May 5, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Edwin M. Stanton to Abraham Lincoln, May 5, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from John P. Usher to Abraham Lincoln, May 6, 1864).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Gideon Welles to Abraham Lincoln, May 5, 1864).

- Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The Committee on the Conduct of the War, p. 200.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 24-25 (May 6, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 345-346 (Letter to Edwin M. Stanton, May 17, 1864).

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 794-795.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 344.

- Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder: The Committee on the Conduct of the War, p. 208.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 345.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 345-346.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 347.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Anonymous to Abraham Lincoln [With Endorsement by Lincoln]1, [June 16, 1864]).

- Ronald C. White, Jr., Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural, p. 176.

- Ronald C. White, Jr., Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural, p. 177.

Visit

Edward Baker (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Edward Baker (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Salmon P. Chase (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

John P. Usher (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Gideon Welles (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)