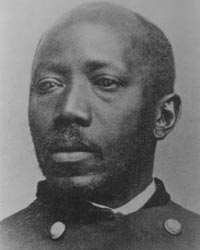

Dr. Martin Delany was the highest ranking black commissioned officer in the Civil War – but the road to that distinction was a long one. “As early as October, 1861, Dr. Delany, when en route to Chicago, stopped at Adrian, Michigan, for the purpose of seeing President Mahan, of the Michigan College. The subject of the war, which was then being earnestly waged, instantly became the theme of conversation, and the rôle of the colored American as an actor on its board was the principal feature therein. How and what to do to obtain admission to the service, was the question to which Dr. Delany demanded a solution. He stated that it had become inseparable with his daily existence, almost absorbing everything else, and nothing would content him but entering the service; he cared not how, provided his admission recognized the rights of his race to do so,” wrote biographer Frank Rollin.

“Dr. Delany at once proposed that the application be made specially for a corps d’Afrique for signal service from the white division of the army. This was prior to the application of Dr. Gloucester to Mr. Lincoln for such an organization for Major General Fremont, or the order to General N.P.Banks,” wrote Rollin. “His main reason in urging the corps d’Afrique was, he claimed, with his usual pride of race, that the origin and dress of the Zouaves d’Afrique were strictly African.” Delany’s vision was not soon realized.

Charles V. Dyer wrote President Lincoln in late April 1863: “Doctor Martin R. Delany is a reliable man and as you can not fail to discover a man of energy and intelligence – and any monies that may be placed in his hands will be faithfully and legitimately applied as shall be stipulated”1 Less than a week later, Peter Page wrote Mr. Lincoln: “The bearer of this, Dr Delany, is a man (who from the short acquaintance I have had with him, & what I have read of his operations, & explorations in Africa) I think eminently qualified to conduct an enterprise of Colonization of the free colored people of this country, should that be thought the best way to dispose of them. I therefore take great pleasure in reccommending [sic] him to your favorable consideration.”2

But it took nearly two more years before the Virginian-born, Pennsylvania-raised, Harvard-educated doctor to be personally greeted at the White House. He may have appealed to Mr. Lincoln because like the President he had been a strong proponent of black emigration or colonization. Delany, who wrote The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States, had even visited Africa in 1859 to prepare the way for a group of black emigrants, but the Civil War had turned his attentions homeward and to the recruitment of black soldiers. He became one of the relatively few blacks to serve as an officer in the Union army.

But it wasn’t until February 1865 that Dr. Delany met President Lincoln at the White House and was immediately commended to Secretary of War for an army commission. “The 6th of February, 1865, found him in Washington, for the purpose of having an interview, if possible, with President Lincoln and the secretary of war. To his friend, the Rev. Henry Highland Garnet, whose guest he was, he made known the principles on which he based his intended interview,” wrote Rollin. “Mr. Garnet, living in Washington, and cognizant of every measure inaugurated among the colored people relative to the war, and remembering their ill success with the executive, at first attempted to discourage him. Mr. Garnet said to him, “Don’t aim to say too much in that direction. While your position is a good one, yet I am afraid you will not see the president. So many of our men have called upon him of late, all expecting something, and coming away dissatisfied, some of them openly complaining, that I am fearful he has come to the conclusion to receive no more black visitors.” To this he replied, “Mr. Garnet, I see you are mistaken in regard to my course. I am here to ask nothing of the president, but to offer him something for the government. If it suits him, and he accepts, I will take anything he may offer me in return.”3

The meeting took place on February 8, 1865. Delany dictated his version of his meeting with the President to Frank Rollin, who wrote a biography in 1883:

On entering the executive chamber and being introduced to his excellency, a generous grasp of the hand brought me to a seat in front of him. No one could mistake the fact that an able and master spirit was before me. Serious with sadness, and pleasant withal, he was soon seated, placing himself at ease, the better to give me a patient audience. He opened the conversation first.

“What can I do for your, sir?” he inquired.

“Nothing, Mr. President,” I replied, “but I’ve come to propose something to you, which I think will be beneficial to this nation in this critical hour of her peril.” I shall never forget the expression of his countenance and the inquiring look which he gave me when I answered him.

“Go on, sir,” he said, as I paused through deference to him. I continued the conversation by reminding him of the full realization of arming the blacks of the South, and the ability of the blacks of the North to defeat it by complicity with those at the South, through the medium of theUnderground Railroad, a measure known only to themselves.

I next called his attention to the fact of the heartless and almost relentless prejudice exhibited towards the blacks by the Union army, and that something ought to be done to check this growing feeling against the slave, else nothing that we could do would avail. And if such were not expedited, all might be lost. That the blacks in every capacity in which they had been called to act, had done their part faithfully and well.

I said: “I would call your attention to another fact of great consideration; that is, the position of confidence in which they have been placed when your officers have been under obligations to them, and in many instances even the army in their power. As pickets, scouts, and guides, you have trusted them, and found them faithful to the duties assigned; and it follows that if you can find them of higher qualifications, they may with equal credit, fill higher more important trusts.’

“Certainly“‘ replied the president, in his most emphatic manner. “And what do you propose to do?” he inquired.

I responded, “I propose this, sir; but first permit me to say that, whatever I may desire for black men in the army, I know that there exists too much prejudice among the whites for the soldiers to serve under a black commander, or the officers to be willing to associate with him. These are facts which must be admitted, and, under the circumstances, must be regarded, as they cannot be ignored. And I propose, as a most effective remedy to prevent enrolment of the blacks in the rebel service, and induce them to run to, instead of from, the Union forces, the commissioning and promotion of black men now in the army, according to merit.”

Looking at me for a moment, earnestly, yet anxiously, he demanded, “How will you remedy the great difficulty you have just now so justly described, about the objections of white soldiers to colored commanders, and officers to colored associates?”

I replied: “I have the remedy, Mr. President, which has not yet been stated; and it is the most important suggestion of my visit to you. And I think it is just what is required to complete the prestige of the Union army. I propose, sir, an army of blacks, commanded entirely by black officers, except such whites as may volunteer to serve; this army to penetrate through the heart of the South, and make conquests, with the banner of Emancipation unfurled proclaiming freedom as they go, sustaining and protecting it by arming the emancipated taking them as fresh troops, and leaving a few veterans among the new freemen, when occasion requires, keeping this banner unfurled until every slave is free, according to the letter of your proclamation.”

“I would also take from those already in the service all that are competent for commission officers, and establish at once in the South a camp of instructions. By this we could have in about three months an army of forty thousand blacks in motion, the presence of which anywhere would itself be a power irresistible. You should have an army of blacks, President Lincoln, commanded entirely by blacks, the sight of which is required to give confidence to the slaves and retain them to the Union, stop foreign intervention, and speedily bring the war to a close.”

“This,” replied the president, “is the very thing I have been looking and hoping for; but nobody offered it. I have thought it over and over again. I have talked about it; I hoped and prayed for it; but till now, it never has been proposed. White men couldn’t do this, because they are doing all in that direction now that they can; but we find, for various reasons, it does not meet the case under consideration. The blacks should go to the interior, and the whites be kept on the frontiers.”

“Yes, sir” I interposed; “they would require but little, as they could subsist on the country as they went along.”

“Certainly,” continued he; “a few light artillery with the cavalry would comprise your principal advance, because all the siege work would be on the frontiers and waters, done by the white division of the army. Won’t this be a grand thing?” he exclaimed, joyfully. He continued, “When I issued the Emancipation Proclamation, I had this thing in contemplation. I then gave them a chance by prohibiting any interference on the part of the army; but they did not embrace it,” said he, rather sadly, accompanying the word with an emphatic gesture.

“But, Mr. President,” said I, “these poor people could not read your proclamation, nor could they know anything about it, only, when they did hear, to know that they were free.”

“But you of the North I expected to take advantage of it,” he replied.

“Our policy, sir,” I answered, “was directly opposite, supposing that it met your approbation. To this end, I published a letter against embarrassing or compromising the government in any manner whatever; for us to remain passive, except in case of foreign intervention, then immediately to raise the slaves to insurrection.”

“Ah, I remember the letter,” he said, “and thought at the time that you mistook my designs. But the effect will be better as it is, by giving character to the blacks, both North and South, as a peaceable, inoffensive people.” Suddenly turning, he said, “Will you take command?”

“If there be none better qualified than I am, sir, by that time I will. While it is my desire to serve, as black men we shall have to prepare ourselves, as we have had no opportunities of experience and practice in the service as officers.”

“That matters but little, comparatively,’ he replied; ‘as some of the finest officers we have never studied the tactics till they entered the army as subordinates. And again,’ said he, ‘the tactics are easily learned, especially among your people. It is the head that we now require most, men of plans and executive ability.”

“I thank you, Mr. President,” said I, “for the. . .”

“No, not at all,” he interrupted.

“I will show you some letters of introduction, sir,” said I, putting my hand in my pocket to get them.

“Not now,” he interposed; “I know all about you. I see nothing now to be done but to give you a line of introduction to the secretary of war.”

Just as he began writing the cannon commenced booming.

“Stanton is firing! Listen! He is in his glory! Noble man!” he exclaimed.

“What is it, Mr. President?” I asked.

“The firing!”

“What is it about, sir?” I reiterated, ignorant of the cause.

“Why, don’t you know? Haven’t you heard the news? Charleston’s ours!’ he answered, straightening up from the table on which he was writing for an instant, and then resuming it. He soon handed me a card, on which was written:

February 8, 1865

Hon. E. M. Stanton, Secretary of War

Do not fail to have an interview with this most extraordinary and intelligent black man.”

A. Lincoln 4

Delaney was commissioned as the U.S. Army’s first black field officer 19 days later. Delany had already lived an eventful life. He was a prolific writer on the conditions of Americans in America and in Africa.

Footnotes

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Charles V. Dyer to Abraham Lincoln, April 26, 1863).

- Frank A. Rollin, Life and Public Service of Martin R. Delany, p. 162-163.

- Frank A. Rollin, Life and Public Service of Martin R. Delany, p. 166-171.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Peter Page to Abraham Lincoln1, May 1, 1863).