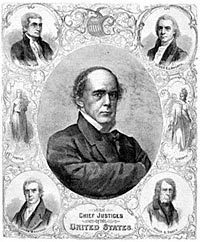

“The second man in importance and ability to be put into the Cabinet was Mr. [Salmon P.] Chase, of Ohio,” wrote fellow Administration official Charles A. Dana. “He was an able, noble, spotless statesman a man who would have been worthy of the best days of the old Roman republic. He had been a candidate for the presidency, though a less conspicuous one than Seward. Mr. Chase was a portly man; tall, and of an impressive appearance, with a very handsome, large head. He was genial, though very decided, and occasionally he would criticize the President, a thing I never heard Mr. Seward do. Chase had been successful in Ohio politics, and in the Treasury Department his administration was satisfactory to the public. He was the author of the national banking law. I remember going to dine with him one day – I did that pretty often, as I had known him well when I was on the Tribune – and he said to me: ‘I have completed to-day a very great thing. I have finished the National Bank Act. It will be a blessing to the country long after I am dead.'”1

Historian Allan Nevins wrote that the prospect of war made Chase cautious in March 1861. Chase “had gone into the Cabinet with the reputation of an unflinching radical, the doughtiest champion of those whom C[harles]. F. Adams called the ramwells – that is, the diehards. But at the moment it was actually true that, as Greeley’s Washington correspondent wrote, he was no extremist, but ‘moderate, conciliatory, deliberate, and conservative.’ One important factor in his hesitation was his fear that a war would be very difficult, and perhaps impossible, to finance. He was under pressure from Eastern bankers who had warned him that they would not take his pending eight-million-dollar loan unless the government pursued a peace policy. Now he wrote Lincoln that if relieving the fort meant enlisting huge armies and spending millions, he would not advise it. It was only because he believed that the South might be cajoled by full explanations and other conciliatory gestures into accepting the relief effort without war that he supported it. That is, he was for relief only with careful explanations.”2

Chase was as difficult as he was capable. Pennsylvania editor Alexander K. McClure wrote: “Salmon P. Chase was the most irritating fly in the Lincoln ointment from the inauguration of the new administration in 1861 until the 29th of June, 1864, when his resignation as Secretary of the Treasury was finally accepted. He was an annual resigner in the Cabinet, having petulantly tendered his resignation in 1862, again in 1863, and again in 1864, when he was probably surprised by Mr. Lincoln’s acceptance of it. It was soon after Lincoln’s unanimous renomination, and when Chase’s dream of succeeding Lincoln as President had perished, at least for the time. He was one of the strongest intellectual forces of the entire administration, but in politics he was a theorist and a dreamer and was unbalanced by overmastering ambition.”3

Salmon Portland Chase was born in 1808 in New Hampshire, the son of a farmer-manufacturer. His father died when he was nine and when he was 12, he was sent to Ohio to leave with his Uncle Philander where he was educated as schools his uncle headed until he was 15. Like Mr. Lincoln, he found farming chores distasteful. He returned to New Hampshire where he entered Dartmouth as a 16-year-old sophomore, graduating when he was 18. Like eventual Republican rival William H. Seward, he tried an early stint at teaching. He taught school while in college and on graduation went to Washington on his uncle’s recommendation where he spent three years as a teacher. He was not, however, very patient in teaching or politics.

Chase’s high birth helped to give him a high opinion of himself. According to biographer John Niven, “As a politician he was not trusted even by close associates. His family and his education marked him as an aristocrat in the frontier city where he settled. And even after Cincinnati became a more populous, cosmopolitan urban center in the 1840s and 1850s. Chase’s eastern college background and his Episcopalian faith did not evoke the mass enthusiasm that would have made him more attractive to his political associates.”4

Chase studied law without much diligence, was admitted to the bar at age 24, and moved to Cincinnati to begin his practice. (In Washington, he had become something of a protégé of Attorney General William Wirt, who acted as a father figure to him.) He was perhaps a better editor and writer than attorney; in 1832 Chase published a edition of the collected laws of Ohio that gained him a legal reputation in Ohio and adjoining states. He subsequently won sufficient bank business to make his legal profession a profitable one. He took on a succession of partners and a parade of legal clerks, who were expected to aid in Chase’s own political pursuits as well as his legal ones.

In marriage, Chase had less luck than in the law. His first wife died less than two years after their marriage in 1834; their daughter died before she reached five. He had three daughters by his second marriage in 1839; two daughters died as did his wife in 1845. His third marriage in 1846 lasted only six years before his wife died, survived by one of their two children.

Progressively during the 1830s, Chase was drawn into the association with abolitionists James Birney (a newspaper editor who later moved to New York) and Gamaliel Bailey – and into legal cases on behalf of the abolitionist cause. In so doing, he seems to have been motivated primarily by religious and moral reasons. There certainly was no political advantage to Chase, since Cincinnati was too close to the South to encourage abolitionist thinking. He developed a reputation as the “attorney general of fugitive slaves” – even though he lost all of his cases.5 Chase argued repeatedly: “The honor, the welfare, the safety of our country, imperiously require the absolute and unqualified divorce of the government from slavery.”6

Chase advocated the “denationalization of slavery” – restricting it in all places over which the federal government had control and limiting to slave-holding states. According to Chase, the Constitutional prohibition against deprivation of “life, liberty or property except by due process of law” meant that the Constitution could not be used to justify slavery.

Chase’s political career was much more checkered than Mr. Lincoln’s. He spent most of the 1830s as a Whig, abandoning that party in 1841 for the Liberty Party, then helping to organize the Free Soil Party in 1848. He became a Democrat with his election to the Senate in 1849 (over Whig Joshua Giddings) and was effectively frozen out of Senate business and the Democratic caucus by his abolitionist ideas. He was also pro-immigrant, pro-land grants, but anti-pork. Along with New York Senator William H. Seward he gave one of the great speeches against the Compromise of 1850 although he lacked much personal or political empathy with Seward. He worked during this period to strengthen “free Democracy” without much success.

Like Mr. Lincoln, he cultivated the newspaper editors. Like Mr. Lincoln, he was appalled by mobs – as when mobs threatened newspaper editor James Birney (in a case similar to that of Elijah Lovejoy in Illinois) Like Mr. Lincoln, he helped found a “Lyceum,” and one of the lectures he delivered was entitled the “Effects of Machinery.” Unlike Mr. Lincoln, he was not a good stump speaker but he was a good writer, especially of political platforms. He was better at speaking to small groups than with large audiences. Biographer Albert Bushnell Hart wrote: “Though Chase never could learn the quickness and adroitness which made Seward and [John] Hale such formidable debaters, he knew how to argue, and especially how to state great principles in a popular form.”7 Biographer Hart wrote: “It was not in Chase’s nature to be persuasive; in all his public life his successes were those of the downright man, convincing without pleasing. Himself a most capable legislator when in the Senate, he had little patience with slow intellects, and less of that urbane yielding of non-essentials which secures the adoption of the larger matters of principle.”8

Chase was also a good slogan maker. In the Senate, he coined the phrase: “Freedom is national; slavery only is local and sectional.” He wrote President-elect Lincoln, “let the word pass from the head of the column before the Republicans move…the simple watchword – Inauguration first – adjustment afterwards.”9 He also came up with “In God We Trust.”10 He coined the phrase, “Free Soil, Free Labor and Free Men.”

Historian Eric Foner wrote: “Chase’s interpretation of the Constitution thus formed the legal basis for the political program which was created by the Liberty party and inherited in large part by the Free Soilers and Republicans….In 1850, Chase wrote to Charles Sumner that his political outlook could be summarized in three ideas: 1. That the original policy of the Government was that of slavery restriction. 2. That under the Constitution Congress cannot establish or maintain slavery in the territories. 3. That the original policy of the Government has been subverted and the Constitution violated for the extension of slavery, and the establishment of the political supremacy of the Slave Power.”11

In 1854, Senator Chase was responsible for the “Appeal of the Independent Democrats in Congress to the People of the United States” – a strong criticism of Douglas’ proposal on slavery. He was one of the leading constitutional theorists for the anti-slavery movement. “Chase developed an interpretation of American history which convinced thousands of northerners that anti-slavery was the intended policy of the founders of the nation, and was fully compatible with the Constitution. He helped develop the idea that southern slaveholders, organized politically as a Slave Power, were conspiring to dominate the national government, reverse the policy of the founding fathers, and make slavery the ruling interest of the republic.”12

In some ways, he was caught between his ambition and his sense of duty. Like Mr. Lincoln, he had trouble helping to provide for his relatives, especially his alcoholic brother Alexander and younger brother William. But Chase had even less luck with political friends. His pursuit of compromise among those who were not accustomed to compromise led to misunderstandings and accusations of betrayal – especially when he was nominated to the U.S. Senate. He sought to replace James Birney as the presidential candidate of the Liberty Party in 1848. As biographer John Niven noted: “From that encounter and kindred experiences he learned that one must be very careful with abolitionists, who dealt in moral absolutes. They were a querulous, changeable lot, suspicious and with good reason of political parties. Coming from an evangelistic tradition – many of them Protestant ministers – they were accustomed to exhortation and moral persuasion through the religious press, pamphlets, books and lectures. Most considered themselves missionaries carrying God’s will to a heathen nation.”13 Niven quotes John McLean as observing: “Chase is the most unprincipled man politically that I have ever known. He is selfish beyond any other man, and I know from the bargain he has made in being elected to the Senate, he is ready to make any bargain to promote his interest.”14 In his biography, Frederick Blue observed of Chase in 1848: “…at this early stage in his career, he sought high station instead by operating as a manager and organizer, a behind-the-scenes ‘compromiser’ who also turned his private tragedies into deep, uncompromising concerns for the oppressed.”15

Curiously, Chase was both a moral puritan and an opportunistic politician. Chase lacked charisma but he had no lack of moral rectitude. He lacked a knack for political manipulation. He sought the Republican presidential nomination in 1856 but suffered from a divided Ohio delegation. His reelection in 1857 suffered from revelations of corruption within his own administration (but not him) – he won by only 1500 votes. Part of Chase’s problem was that his own concept of moral error was not shared. Purity conflicted with deal-making. One Democratic leader told some Cincinnati men: “Boys! I see you have been talking with Chase. He is courting you young men. Avoid him. He is a political vampire. No! He’s a sort of moral bull-bitch.”16 His subordinates at the Treasury Department frequently did not have the same rectitude – whether supervising customs or the cotton trade. William Reynolds, the Chase appointee for Port Royal, was one of those associated with corruption.17 Problems with his appointees led to a confrontation with President Lincoln and Chase’s resignation in late June 1864.

Fellow Ohioan Benjamin Wade said of Chase: “Chase is a good man, but his theology is unsound. He thinks there is a fourth person in the Trinity.”18 Biographer Albert Bushnell Hart wrote: “As a politician, Chase lacked conciliation and alertness; yet he did first and last win many votes for the measures and the men whom he supported. He was in large degree an opportunist. In the Kansas-Nebraska Bill, where his qualities as a man were perhaps more clearly revealed than in any other episode of his life, he did everything that could be done to modify the bill, except to give up the principles upon which his objection was founded….,”

But Chase’s moralism had an important impact wrote biographer Hart. “Chase saw more clearly than any other public man of his time, except Lincoln, the importance, the necessity, and the moral effect of sticking to a consistent principle. He entered public life as an anti-slavery man, and nothing ever drew him aside from what he conceived to be the right of the bondman, and the parallel right of the community to be freed from bondage.”19 He had difficulty inspiring warm political allies, but managed to be a mentor to many younger politicians and lawyers like future President James Garfield.

Biographer Albert Bushnell Hart wrote: …in his own lifetime Chase had fewer warm friends and admirers than almost any one of these rivals, and that somehow he repeatedly gave an impression of smallness in small matters, which dimmed his reputation. This came first of all from his measuring himself with Lincoln, and in that unhappy difference he did not show a great man’s appreciation of another great man’s character and personality.”20 That deficiency was clear at the 1860 Republican National Convention. At the State Convention, Chase was endorsed 375-73. Unlike Mr. Lincoln, he did not assure the unity of his home state delegation in 1860. He got 34 of the state’s votes on the first ballot; 12 delegates supported other candidates. He got only 15 votes from other non-Ohio delegates. However, the chairman of the Ohio delegation, former Congressman David Carrter, was not a strong Chase Partisan. And, noted biographer John Niven, Senator “Ben Wade was running a covert campaign in part to block Chase for whom he had formed a distinct personal dislike and in part because he thought his credentials were as good if not better than any other western man for the nomination.”21 At the Chicago convention, David Carrter changed four votes to Lincoln when he stuttered: “I rise (eh) Mr. Chairman (eh), to announce the change of four votes of Ohio from Mr. Chase to Mr. Lincoln.”22 Chase simply did not inspire enthusiasm or loyalty.

Chase had again been elected to the Senate on February 3, 1860, defeating George Pugh, the Democrat who had been elected to succeed him six years earlier. He had to relinquish that position to join the cabinet in March 1861. After Mr. Lincoln’s election in November 1860, Chase tried to keep New York’s William H. Seward and Indiana’s Caleb Smith out of Lincoln’s cabinet. Chase worried about too many Whigs in the Cabinet. Seward’s friends worried about too many Democrats. Seward tried to keep out Chase, Welles and Blair, all former Democrats. Meanwhile, Senator Chase served as an Ohio representative on the Peace commission and used his influence to see that it did not go anywhere.

Like other members of the Lincoln cabinet, Chase was a busybody who refused to confine his thoughts to his responsibilities. At the beginning of the War, he took particular responsibility for affairs in Kentucky. He also took an active part in military appointments. “Throughout the war Chase kept up his great interest in the conduct of the army, and he maintained close correspondence with many of the commanders, – at first with McClellan, later with Hooker, Lander, H.B. Carrington, Mitchell, Garfield, McCook, W.B. Smith, Benham, and many others. Western officers and politicians were especially fond of seeking his military influence,” wrote biographer Bushnell.23 Chase’s own responsibilities include a trade, revenue, and expenditures as well as some elements of reconstruction.

Patronage was important to cabinet officers. They were not shy about imposing their wishes on departments other than their own. Chase interfered in the War Department and criticized Seward for appointing an insufficient number of diplomats from Ohio. Well-placed patronage was one of the great advantages of the Treasury Department. Customs agents were the most lucrative positions, but Chase also utilized agents who worked with freed slaves and in collecting revenue.

Although Chase tried to align patronage with principle, he may have been less successful than he believed. Historian William Frank Zornow wrote: “”When someone implored him once for an appointment on the ground that it would help his campaign for the Presidency, Chase wrote with much repugnance, ‘I should despise myself if I felt capable of appointing or removing a man for the sake of the Presidency.’ Yet on many occasions he betrayed much interest in the matter of making proper appointments for political reasons, and Edward Bates confided in his diary that ‘Mr. Chase’s head is turned by his eagerness in pursuit of the presidency. For a long time back he has been filling all the offices in his own vast patronage with extreme partisans and contrives also to fill many vacancies properly belonging to other departments.’24

“Chase got appointments in other departments for his old law partner, Ball, for his brother, and for other kinsmen, and he himself appointed many other old friends; but the evidence shows that he made it a principle to recognize merit and efficiency, and was glad to find it among his own friends and adherents, all of whom were of course Republicans or strong war Democrats,” wrote Albert Bushnell Hart.25

Historian Burton J. Hendrick wrote: “Chase was opposed to compensated emancipation; he agreed with the abolitionist view that this was giving malefactors payment for the restoration of stolen goods. Colonization, which Lincoln had been advocating for a long time, the Secretary also disapproved. His treatment for the Negro insisted on his elevation, so far as civil rights and citizenship were concerned, to an equality with whites. ‘How much better,’ he said, ‘would be a manly protest against prejudice against color! And a wise effort to give freemen homes in America! A military officer, emancipating at least the slaves of South Carolina, Georgia, and the Gulf States’ – the reference, of course, is to General Hunter, who had attempted the very thing – ‘would do more to terminate the war and ensure an early restoration of solid peace and prosperity than anything else that can be devised.”26

Biographer Frederick J. Blue wrote: “The Sea Islands of South Carolina fell under Union control early in the war when Samuel F. DuPont’s South Atlantic Squadron took the area in November 1861. The Treasury Department, with its responsibility for confiscated and abandoned property, was given the task of administering the region. Because the planters had left behind many of their slaves as they fled inland, Chase had an opportunity to direct the first significant experiment in working with freedmen. In his eyes, those who had been abandoned could never be ‘reduced again to slavery’ by the government ‘without great inhumanity.’ He therefore quickly appointed his abolitionist friend Edward I Pierce of Boston to direct the effort to prepare them ‘for self-support by their own industry.’

Chase understood that he could not only use the Treasury Department to advance himself, politically, he could use the Treasury Department to advance the welfare of freed blacks in the South. “Chase received little encouragement in this effort from the rest of the cabinet or the president,” wrote biographer Frederick J. Blue. “He nonetheless reluctantly authorize Chase to give Pierce ‘such instructions in regard to Port Royal contrabands as may seem judicious.'”27

Blue concluded: “To Chase the war had become a means to his long sought goal of emancipation, whereas to Lincoln emancipation was the means to a successful war and restoration of the Union. In other respects, their relationship had long since begun to deteriorate.”28

Chase’s efforts to use the Treasury Department to advance to collapsed in February 1864 and his relations with the President deteriorated until he resigned at the end of June. Lincoln biographer Alonzo Rothschild wrote that the “seeming indifference of the Preident to his Secretary’s rivalry, as well as Mr. Lincoln’s failure to respond to that gentleman’s professions of affection, greatly mortified Mr. Chase. He had, to be sure, been retained in the cabinet under conditions that would ordinarily have warranted his dismissal; but the relations between him and his superior were, from that time, less cordial even than ever.”29

Even contemporary observers saw Chase’s duplicity. “When the true history of the differences between President Lincoln and Secretary of the Treasury Chase shall be written, it will not redound to the credit of the Secretary or his indiscreet and ambitious friends. The persistent effort of these men to break down the President during a great civil war were discreditable in the extreme,” wrote Ohio newspaperman William H. Smith.30

Footnotes

- Charles A. Dana, Recollections of the Civil War, p. 156.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union: The Improvised War, 1861-1862, p. 45.

- Alexander K. McClure, Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 132.

- Crisis of Republicans, p. 56-57 (John Niven in “Salmon P. Chase and the Republicans”).

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon P. Chase, p. 82-83.

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon P. Chase, p. 92.

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon P. Chase, p. 148.

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon P. Chase, p. 234.

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, p. 233.

- Weldon, p. 129.

- Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War, p. 87.

- Eric Foner, Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party Before the Civil War, p. 73.

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, p. 89.

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, p. 187.

- Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics, p. 67.

- Robert B. Warden, An Account of the Private Life and Public Services of Salmon Portland Chase, p. 250-251.

- Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics, p. 185.

- John Waugh, Reelecting Lincoln, p. 38.

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon P. Chase, p. 429.

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon P. Chase, p. 431.

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, p. 215.

- John Niven, Salmon P. Chase: A Biography, p. 220.

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon P. Chase, p. 214.

- William Frank Zornow, Lincoln & the Party Divided, p. 26-27.

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon P. Chase, p. 219.

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 358.

- Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics, p. 184.

- Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics, p. 189.

- Alonzo Rothschild, Lincoln: Master of Men: A Study in Character, p. 207.

- Allan Nevins, War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865, p. 82.