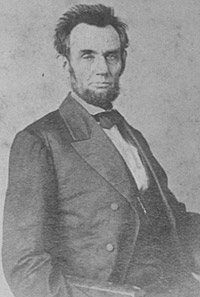

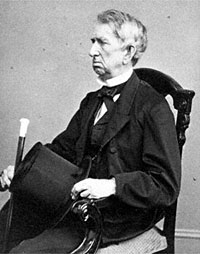

In January 1865, pressure intensified on Mr. Lincoln to bring the Civil War to a speed close. Francis P. Blair, Sr., the influential head of a conservative Republican family, undertook an informal but inconclusive mission to Richmond and reported back to the President. Secretary of State William H. Seward detailed the events leading up to the Hampton Roads conference in a letter to U.S. Minister to England Charles F. Adams:

A few days ago Francis P. Blair, Esq., of Maryland, obtained from the President a simple leave to pass through out military lines, without definite views known to the government. Mr. Blair visited Richmond and on his return he showed to the President a letter which Jefferson Davis had written to Mr. Blair, in which Davis wrote that Mr. Blair was at liberty to say to President Lincoln that Davis was now, as he always had been, willing to send commissioners, if assured they would be received, or to receive any that should be sent; that he was not disposed to find obstacles in forms. He would send commissioners to confer with the President, with a view to a restoration of peace between the two countries, if he could be assured they would be received. The President thereupon, on the 18th of January, addressed a note to Mr. Blair, in which the President, after acknowledging that he had read the note of Mr. Davis, said that he was, is and always should be willing to receive any agents that Mr. Davis or any other influential person now actually resisting the authority of the government might send to confer informally with the President, with a view to the restoration of peace to the people of our one common country. Mr. Blair visited Richmond with this letter, and then again came back to Washington. On the 29th instant we were advised from the camp of Lieutenant General Grant that Alexander H. Stephens, R. M. T. Hunter, and John A. Campbell were applying for leave to pass through the lines to Washington, as peace commissioners, to confer with the President. They were permitted by the Lieutenant General to come to his headquarters, to await there the decision of the President. Major Eckert was sent down to meet the party from Richmond at General Grant’s headquarters. The major was directed to deliver to them a copy of the President’s letter to Mr. Blair, with a note to be addressed to them, and signed by the major, in which they were directly informed that if they should be allowed to pass our lines they would be understood as coming for an informal conference, upon the basis of the aforenamed letter of the 18th of January to Mr. Blair. If they should express their assent to this condition in writing, then Major Eckert was directed to directed to give them safe conduct to Fortress Monroe, where a person coming from the President would meet them. It being thought probable, from a report of their conversation with Lieutenant General Grant, that the Richmond party would, in the manner prescribed, accept the condition mentioned, the Secretary of State was charged by the President with the duty of representing this government in the expected informal conference The Secretary arrived at Fortress Monroe in the night of the first day of February. Major Eckert met him on the morning of the second of February with the information that the persons who had come from Richmond had not accepted, in writing, the condition upon which he was allowed to give them conduct to Fortress Monroe. The major had given the same information by telegraph to the President, at Washington. On receiving this information, the President prepared a telegram directing the Secretary to return to Washington. The Secretary was preparing, at the same moment, to so return, without waiting for instructions from the President; but at this juncture Lieutenant General Grant telegraphed to the Secretary of War, as well as to the Secretary of State, that the party from Richmond had reconsidered and accepted the conditions tendered them through Major Eckert, and General Grant urgently advised the President to confer in person with the Richmond party. Under these circumstances, the Secretary, by the President’s direction, remained at Fortress Monroe, and the president joined him there on the night of the 2d of February. The Richmond party was brought down the James river in a United States steam transport during the day, and the transport was anchored in Hampton Roads.1

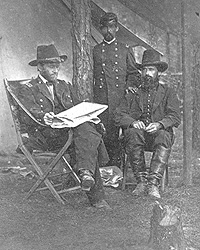

The Hampton Roads meeting set up one of the few moments of obvious friction between President Lincoln and General Grant. Grant wrote in his memoirs:

“On the last of January, 1865, peace commissioners from the so-called Confederate States presented themselves on our lines around Petersburg, and were immediately conducted to my headquarters at City Point. They proved to be Alexander H. Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy, Judge Campbell, Assistant-Secretary of War, and R.M. T. Hunter, former United States Senator and then a member of the Confederate Senate.

It was about dark when they reached my headquarters, and I at once conducted them to the steamer Mary Martin, a Hudson River boat which was very comfortably fitted up for the use of the use of passengers. I at once communicated by telegraph with Washington and informed the Secretary of War and the President of the arrival of these commissioners and that their object was to negotiate terms of peace between the United States and, as they termed it, the Confederate Government. I was instructed to retain them at City Point, until the President, or some one whom he would designate, should come to meet them. They remained several days as guests on board the boat. I saw them quite frequently, though I have no recollection of having had any conversation whatever with them on the subject of their mission. It was something I had nothing to do with, and I therefore did not wish to express any views on the subject. For my own part I never had admitted, and never was ready to admit, that they were the representatives of a government. There had been too great a waste of blood and treasure to concede anything of the kind. As long as they remained there, however, our relations were pleasant and I found them all very agreeable gentlemen. I directed the captain to furnish them with the best the boat afforded, and to administer to their comfort in every way possible. No guard was placed over them and no restriction was put upon their movements; nor was there any pledge asked that they would not abuse the privileges extended to them. They were permitted to leave the boat when they felt like it, and did so, coming up on the bank and visiting me at my headquarters.

I had never met either of these gentlemen before the war, but knew them well by reputation and through their public services, and I had been a particular admirer of Mr. Stephens. I had always supposed that he was a very small man, but when I saw him in the dusk of evening I was very much surprised to find so large a man as he seemed to be. When he got down on to the boat I found that he was wearing a coarse gray woolen overcoat, a manufacture that had been introduced into the South during the rebellion. The cloth was thicker than anything of the kind I had ever seen, even in Canada. The overcoat extended nearly to his feet, and was so large that it gave him the appearance of being an average-sized man. He took this off when he reached the cabin of the boat, and I was struck with the apparent change in size in the coat and out of it.2

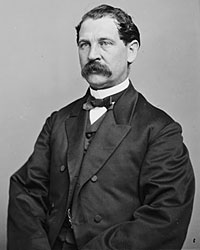

The mood in Washington was less relaxed than at City Point. President Lincoln was determined to maintain control of any peace negotiations and dispatched Major Eckert, head of the War Department’s telegraph office, to make sure that General Grant did not interfere. Major Thomas Eckert was dispatched with two letters. The first was from Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton to Grant – dictated “by order of the President”: “The President desires that you will please procure for the bearer, Major Thomas T. Eckert, an interview with Messrs Stephens, Hunter & Campbell, – and if on his return to you he requests it – pass them through our lines to Fortress Monroe by such route and under such Military precautions as you may deem prudent, giving them protection & comfortable quarters while there; and that you let none of this, have any effect upon your movements or plans.3 The second letter was to Secretary of State William H. Seward:

You will proceed to Fortress-Monroe, Virginia, there to meet, and informally confer with Messrs. Stephens, Hunter, and Campbell, on the basis of my letter to F.P. Blair, Esq. of Jan.18. 1865, a copy of which you have.

You will make known to them that three things are indispensable, towit:

1. The restoration of the National authority throughout all the States.

2. No receding by the Executive of the United States, on the Slavery question, from the position assumed thereon, in the late Annual Message to Congress, and on preceding documents.

3. No cessation of hostilities short of an end of the war, and the disbanding of all forces hostile to the government.4

Meanwhile, Eckert arrived on the steamer River Queen on February 1 and immediately took charge of the proceedings – to Grant’s obvious discomfort, according to the memoirs of Eckert’s Telegraph Office colleague, Homer Bates:

‘Quite a little time,’ he says, ‘was occupied by Stephens asking me how I was, what I had been doing, etc. because he had met me before in 1861 and knew my cousin George in Congress. I sat between Stephens and Hunter. Stephens was very civil in his reception, more so than the others. He asked if they might not begin to discuss the subject. I said, ‘Yes, what is the subject you want to discuss?’ He said, ‘We of the South lay great store by our State rights.’ I turned to him and said, ‘Excuse me, but we in the North never think of that, we cannot discuss that subject at all.’

‘I told them that all the proceedings of the conference must be in writing. I then submitted a copy of my instruction from the President which they took saying they would like to consider it and reply later. Hunter was the chief spokesman, but my communications were always to Stephens, his name being the first on the list of three. Campbell had the least to say. He was, however, a close listener. Before the conference we came very near getting into a difficulty that would have forced me to have done something that might have raised a row, because General Grant wanted to be a party to the conference. I told him no. I said, ‘You are the commanding general of the army. If you make a failure or say anything that would be subject to criticism it would be very bad. If I make a mistake I am nothing but a common business man and it will go for naught. I am going to take the responsibility, and I advise you not to go to the conference.’ He finally said, ‘Decency would compel me to go and see them.’ I said that for the purpose of introduction I should be pleased to have him go with me but not until after I had first met the gentlemen. Grant was vexed with me because I did not tell him exactly what my mission was.

Grant went with me on my second visit a few hours later and after he was introduced, one of the commissioners, I am sure it was Hunter, said to Grant, ‘We do not seem to get on very rapidly with Major Eckert. We are very anxious to go on to Washington, and Mr. Lincoln has promised to see us there.’ General Grant started to make reply when I interrupted him and said, “Excuse me, General Grant, you are not permitted to say anything officially at this time,” and I stopped him right there. I added, ‘If you will read the instructions under which I am acting you will see that I am right.'”

After listening a while to what the commissioners were saying Grant got up and went out. He was angry with me for years afterward, and this has been a source of sincere regret to me, because in his responsible position as commanding general of the army he had some reason for chagrin at the action of a mere major in questioning his ranking authority in the presence of representatives of the government whose army he was fighting. But at the time I gave no thought to this feature of the case, remembering only my explicit orders written and oral from the President. When Grant was stopped from making a reply to Hunter he and the other commissioners doubtless thought that if they could have presented the matter direct to Grant they would likely get his approval. This view is sustained by Grant’s telegram of 10:30 P.m., February 1, 1865.

‘At 9.30 P.M. I informed the commissioners that they could not proceed further unless they complied with the terms recited in my letter of instructions, their formal reply to which had been delivered to me at our earlier interview and to inform General Grant in case they concluded to accept the terms. I then withdrew and sent my cipher-despatch to President Lincoln dated 10 P.M. Feb. 1, advising him that the reply of the Peace Commissioners was ‘not satisfactory.’ The originals of all writings at this conference were taken to Fort Monroe and haded to Secretary Seward.”5

Grant biographer Brooks D. Simpson wrote: “At first it looked as if there would be no meeting. The commissioners would not accede to the president’s preconditions of reunion, abolition, and an end to the conflict; they insisted that they had to comply with Davis’s direction authorizing negotiations to achieve peace between ‘the two countries.’ The Confederates tried to bypass Eckert by appealing directly to Grant to allow them to go to Washington; the major blocked this effort at circumvention. The General was clearly unhappy. Eckert seemed so intent on following the letter of his instructions in his brusque manner that he overlooked the opportunity the commissioners presented. What harm could it do for Lincoln to meet with them? In turn, Grant prodded the commissioners, asking them if they could find it within themselves to soften the wording of their reply so as to open the door to future talks. The commissioners complied: Stephens, having expected to meet a blunt, rude soldier, was pleasantly surprised to find in Grant a reflective, intelligent, and shrewd gentleman.”6

At this point, Grant intervened. He telegraphed Secretary Stanton on February 1: “Now that the interview between Major Eckert, under his written instructions, and Mr. Stephens and party has ended, I will state confidentially, but not officially to become a matter of record, that I am convinced upon conversation with Messrs. Stephens and Hunter that their intentions are good and their desire sincere to restore peace and union. I have not felt myself at liberty to express even views of my own or to account for my reticency. This has placed me in an awkward position, which I could have avoided by not seeing them in the first instance. I fear now their going back without any expression from anyone in authority will have a bad influence. At the same time, I recognize the difficulties in the way of receiving these informal commissioners at this time, and do not know what to recommend. I am sorry, however, that Mr. Lincoln can not have an interview with the two named in this dispatch, if not all three now within our lines. Their letter to me was all that the President’s instructions contemplated to secure their safe conduct if they had used the same language to Major Eckert.”7

Historian Brooks D. Simpson wrote: “Lincoln later said that it was Grant’s telegram that induced him to change his mind and decide to meet the commissioners; he cannily omitted Eckert’s dispatch when he relayed the correspondence to the House of representatives, preferring to emphasize Grant’s agency in the proceedings. In the meantime he had secured congressional passage of the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery which would strengthen his hand in any talks.”8

Grant’s telegram had its intended effect. On February 2, Mr. Lincoln left Washington for Hampton Roads – arriving that night at Fortress Monroe by steamer and conferred with Secretary of State William H. Seward. Civil War historian Shelby Foote wrote: “For Lincoln, this put a different face on the matter. He got off two wires at once. One was to Seward, instructing him to remain where he was. The other was to Grant. ‘Say to the gentlemen I will meet them personally at Fortress Monroe as soon as I can get there.'” According to Foote, “He left within the hour, not even taking time to notify his secretary or any remaining member of his cabinet, and by nightfall was with Seward aboard the steamer River Queen, riding at anchor under the guns of Fort Monroe. T he rebel commissioners were on a nearby vessel,, also anchored in Hampton Roads; Seward had not seen them yet, and Lincoln sent word that he would receive them next morning in the Queen’s saloon. His instructions to the Secretary of State had been brief and to the point, listing three ‘indispensable’ conditions for peace.”9

General Grant wrote in his memoirs: “After a few days, about the 2d of February, I received a dispatch from Washington, directing me to send the commissioners to Hampton Roads to meet the President and a member of the cabinet. Mr. Lincoln met them there and had an interview of short duration. It was not a great while after they met that the President visited me at City Point. He spoke of his having met the commissioners, and said he had told them that there would be no use in entering into any negotiations unless they would recognize, first: that the Union as a whole must be forever preserved, and second: that slavery must be abolished. If they were willing to concede these two points, then he was ready to enter into negotiations and was almost willing to hand them a blank sheet of paper with his signature attached for them to fill in the terms upon which they were willing to live with us in the Union and be one people. He always showed a generous and kindly spirit toward the Southern people, and I never heard him abuse an enemy. Some of the cruel things said about President Lincoln, particularly in the North, used to pierce him to the heart; but never in my presence did he evince a revengeful disposition – and I saw a great deal of him at City Point, for he seemed glad to get away from the cares and anxieties of the capital.10

General Grant wrote in his memoirs: “After a few days, about the 2d of February, I received a dispatch from Washington, directing me to send the commissioners to Hampton Roads to meet the President and a member of the cabinet. Mr. Lincoln met them there and had an interview of short duration. It was not a great while after they met that the President visited me at City Point. He spoke of his having met the commissioners, and said he had told them that there would be no use in entering into any negotiations unless they would recognize, first: that the Union as a whole must be forever preserved, and second: that slavery must be abolished. If they were willing to concede these two points, then he was ready to enter into negotiations and was almost willing to hand them a blank sheet of paper with his signature attached for them to fill in the terms upon which they were willing to live with us in the Union and be one people. He always showed a generous and kindly spirit toward the Southern people, and I never heard him abuse an enemy. Some of the cruel things said about President Lincoln, particularly in the North, used to pierce him to the heart; but never in my presence did he evince a revengeful disposition – and I saw a great deal of him at City Point, for he seemed glad to get away from the cares and anxieties of the capital.11

On February 3, President Lincoln met with the Confederate representatives. Seward biographer John Taylor wrote: “Lincoln and Seward told the Confederates that the Thirteen Amendment, abolishing slavery, was about to be sent to the states for ratification. The administration, including Seward, had lobbied strongly, for the amendment, on the ground that the South must understand that there was to be no compromise on the slavery issue. Now, aboard the River Queen, Seward sought to entice the Southerners. If the Southern states were to return to the Union, they would be in a position to block ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment and thereby to delay the end of slavery. If Stephens’s account of the conference is credited, Seward held out to the defeated Confederates not only the prospect of delaying the abolition of slavery but of regaining the South’s political clout in a restored union. Seward had come a long way since his reformist phase as a U.S. senator.”12 Presidential aide John G. Nicolay wrote his fiancé what he learned of the meeting:

They had on yesterday, a four hours’ interview with them. It was a long and rambling talk, entirely friendly and courteous, and also informal. Nothing was written

Of course it would be impossible to give an outline of a four hours conversation; but substantially the talk amounted to this: the President told them that he could not entertain any proposition, or conversation which did not concede and embody the restoration of the national authority over the states now in revolt. That he could not recede in the least from what he had publicly said about slavery; and that he could [not] concede or agree to any cessation of hostilities, which was not an actual end of the war and a disbandment of the rebel armies.

They on their side neither offered nor declined any distinct point or proposition; but the drift of all their talk was that they desired a cessation of hostilities, or armistice, or as they phrased it ‘a postponement of the issue.’ So the conference broke up without any result of or conclusion, or even without broaching or debating any points or propositions.13

Historian John Taylor wrote: “Although the meeting on the River Queen was cordial, it was fruitless, for the Confederate emissaries had no authority to negotiate reunion. There were friendly handshakes as the conference broke up. Lincolns promised Stephens to return his nephew, a prisoner on Johnson’s Island. The Confederate emissaries had returned to their steamer when they spied a rowboat with a black oarsman heading for them from the River Queen. When he reached the Confederate vessel, the oarsman passed up a basket of champagne with a note that it came with Mr. Seward’s compliments. Then the three emissaries spotted Seward himself, calling to them through a boatswain’s trumpet. His words were, ‘Keep the champagne, but return the Negro.'”14 Seward wrote to the American minister to England, Charles Francis Adams:

On the morning of the 3d the President, attended by the Secretary, received Messrs. Stephens, Hunter, and Campbell on board the United States stream transport River Queen, in Hampton Roads. The conference was altogether informal. There was no attendance of secretaries, clerks, or other witnesses. Nothing was written or read. The conversation, although earnest and free, was calm, and courteous, and kind on both sides. The Richmond party approached the discussion rather indirectly, and at no time did they either make categorical demands, or tender formal stipulations, or absolute refusals. Nevertheless, during the conference, which lasted four hours, the several points at issue between the government and the insurgents were distinctly raised, and discussed fully, intelligently, and an amicable spirit. What the insurgent party seemed chiefly to favor was a postponement of the question of separation, upon which the war is waged, and a mutual direction of efforts of the government, as well as those of the insurgents, to some extrinsic policy or scheme for a season, during which passions might be expected to subside, and the armies be reduced, and trade and intercourse between the people of both sections resumed. It was suggested by them that through such postponement we might now have immediate peace, with some not very certain prospect of an ultimate satisfactory adjustment of political relations between this government and the States, section, or people now engaged in conflict with it.

This suggestion, though deliberately considered, was nevertheless regarded by the President as one of armistice or truce, and he announced that we can agree to no cessation or suspension of hostilities, except on the basis of the disbandment of the insurgent forces, and the restoration of the national authority throughout all the States in the Union. Collaterally, and in subordination to the proposition which was thus announced, the anti-slavery policy of the United States was reviewed in all its bearings, and the President announced that he must not be expected to depart from the positions he had heretofore assumed in his proclamation of emancipation and other documents, as these positions were reiterated in his last annual message. It was further declared by the President that the complete restoration of the national authority everywhere was an indispensable condition of any assent on our part to whatever form of peace might be proposed. The President assured the other party that, while he must adhere to these positions, he would be prepared, so far as power is lodged with the Executive, to exercise liberality. His power, however, is limited by the Constitution; and when peace should be made, Congress must necessarily act in regard to appropriations of money and to the admission of representatives from the insurrectionary States. The Richmond party were then informed that Congress had, on the 31st ultimo, adopted by a constitutional majority a joint resolution submitting to the several States the proposition to abolish slavery throughout the Union, and that there is every reason to expect that it will be soon accepted by three-fourths of the States, so as to become a part of the national organic law.

The conference came to an end by mutual acquiescence, without producing an agreement of views upon the several matters discussed, or any of them. Nevertheless, it is perhaps of some importance that we have been able to submit our opinions and views directly to prominent insurgents, and to hear them in answer in a courteous and not unfriendly manner.15

Seward biographer Glyndon Van Deusen wrote: “Discussion of the cessation of hostilities inevitably brought up the Negro question. Here, too, Seward and Lincoln had similar views. Both were for liberal treatment of a South that laid down its arms. Both appeared to regard the Emancipation Proclamation as a war measure that would terminate with the end of the struggle. They agreed that, if the war now ceased, the Proclamation would apply to only about 200,000 of the 4,000,000 southern Negroes. The status of the remainder would be subject to judicial construction.”16

However, according to Lincoln biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay: “Mr. Seward brought to the notice of the commissioners one topic which to them was new; namely that only a few days before, on the 31st of January, Congress had passed the Thirteenth Amendment of the Constitution, which, when ratified by three-fourths of the States, would effect an immediate abolition of slavery throughout the entire Union. The reports of the commissioners represent Mr. Seward as saying that if the South would submit and agree to immediate restoration, the restored States might yet defeat the ratification of this amendment, intimating that Congress had passed it ‘under the predominance of revolutionary passion,’ which would abate on the termination of the war. It may well be doubted whether Mr. Seward stated the case as strongly as the commissioners intimate, since he himself, like Mr. Lincoln and his entire cabinet, had favored the measure. It is probable that the commissioners allowed their own feelings and wishes to color too strongly the hypothesis he stated, and to interpret as a probability what he mentioned as only among the possible events of the future.”17

Historian Brooks D. Simpson wrote of the Confederate commissioners that “Even Julia Grant was surprised by their stand. She had chatted with the commissioners, finding them reasonable men. Thus the news that the negotiations had fallen apart took her by surprise. She soon confronted Lincoln. ‘Why, Mr. President, are you not going to make terms with them. They are our own people, you know.'” President Lincoln showed Julia Grant his proposal to the Confederate and she replied: “Why, what do they want? That paper is most liberal.”18

Contemporary Lincoln biographer Isaac Arnold, who was serving in Congress at the time. “The rebel agents earnestly desired a temporary cessation of hostilities, and a postponement of the questions, but to this the President would not listen. So far from it, Mr. Lincoln said to General Grant: ‘Let nothing that is transpiring change, hinder, or delay your military movements or plans.’ The conference ended without accomplishing anything.”

On February 4, President Lincoln returned to Washington General Grant recalled an anecdote of Mr. Lincoln’s reaction to the proceedings: “It was on the occasion of his visit to me just after he had talked with the peace commissioners at Hampton Roads. After a little conversation, he asked me if I had seen that overcoat of Stephens’s. I replied that I had. ‘Well,’ said he, ‘did you see him take it off?’ I said ye. ‘Well,’ said he, ‘didn’t you think it was the biggest shuck and the littlest ear that ever did see?’ Long afterwards I told this story to the Confederate General J.B. Gordon, at the same time a member of the Senate. He repeated it to Stephens, and, as I heard afterwards, Stephens laughed immoderately at the simile of Mr. Lincoln.”19 Secretary of the Interior John Palmer Usher recalled what happened at the next Cabinet meeting:

“When he returned from the James, where he met Messrs. Stephens, Campbell, and Hunter, he related some of his conversations with them. He said that at the conclusion of one of his discourses, detailing what he considered to be the position in which the insurgents were placed by the law, they replied:

‘Well, according to your view of the case we are all guilty of treason, and liable to be hanged.’

Lincoln replied:

‘Yes, that is so.’

They, continuing, said:

‘Well, we suppose that would necessarily be your view of our case, but we never had much fear of being hanged while you were President.’

From his manner in repeating this scene he seemed to appreciate the compliment highly. There is no evidence in his record that he ever contemplated executing any of the insurgents for their treason. There is no evidence that he desired any of them to leave the country, with the exception of Mr. Davis. His great, and apparently his only object was to have a restored Union.20

Meanwhile, wrote Lincoln biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay, the Confederate “commissioners returned to Richmond in great disappointment, and communicated the failure of their efforts to Jefferson Davis, whose chagrin was as great as their own. They had all caught eagerly at the hope that this negotiation would somehow extricate them from the dilemmas and dangers whose crushing portent they realized, but had no power to avert except by surrender; and now, when this last hope failed them, they were doubly cast down. Campbell says he ‘favored negotiations for peace’ – doubtless meaning by this language that he advocated the acceptance of the proffered terms. Stephens yet believed that Mr. Lincoln would be tempted by the Mexican scheme and would reconsider his decision. He therefore advised that the results of the meeting should be kept secret; and when the other commissioners and Davis refused to follow this advice, he gave up the Confederate cause as hopeless, withdrew from Richmond, abandoned the rebellion, and went into retirement. His signature to the brief public report of the commissioners stating the result of the Hampton Roads Conference was his last participation in the ill-starred enterprise.”21

Historian Richard N. Current wrote: “If the reports of Stephens and his colleagues are to be trusted, Lincoln, as of February 3, 1865, would have undertaken a peace of reconciliation, a peace of almost unbelievable generosity. The Southerners needed only to lay down their arms and acknowledge and obey the Federal laws. They would then be pardoned, their rights and property restored (with few exceptions). Their states promptly would be put back into the old ‘practical relations’ with the Union. Slaveowners could even keep their slaves, at least for a time.”22

Members of Congress were already suspicious of the President’s Reconstruction policies. Pennsylvania’s Thaddeus Stevens introduced a congressional resolution to determine what happened at Hampton Roads: “Resolved, That the President be requested to communicate to this House such information as he may deem not incompatible with the public interest, relative to the recent conference between himself and the Secretary of State, and Messrs. Stephens, Hunter and Campbell in Hampton Roads.”23 The Lincoln Administration complied.

Footnotes

- Richard B. Harwell, editor, The Union Reader, p. 326-328.

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, p. 404-405.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 279 (Letter from Edwin M. Stanton to Ulysses S. Grant, January 30, 1865).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 279 (Letter to William H. Seward, January 31. 1865).

- David Homer Bates, Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, p. 335-338.

- Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant, p. 406-407.

- William S. McFeely, Grant: A Biography, p. 204.

- Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant, p. 407.

- Shelby Foote, The Civil War, Volume III, p. 774-775.

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, p. 404-405.

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, p. 404-405.

- John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward: Lincoln’s Right Hand, p. 236.

- John M. Taylor, William Henry Seward: Lincoln’s Right Hand, p. 236.

- Richard B. Harwell, editor, The Union Reader, p. 326-330.

- Glyndon Van Deusen, William Henry Seward, p. 385.

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume X, p. 125-126.

- Brooks D. Simpson, Ulysses S. Grant, p. 407.

- Ulysses S. Grant, Personal Memoirs of U.S. Grant, p. 405.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 97-98 (John Palmer Usher).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 173 (Letter from John G. Nicolay to Therena Bates, February 4, 1865).

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume X, p. 129.

- Richard Nelson Current, The Lincoln Nobody Knows, p. 247.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (House of Representatives, Resolution Requesting Information on Hampton Roads Conference, February 8, 1865).