Abolitionist dissidents meeting in Cleveland on May 30, 1864 included in their new party platform support for a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. “When the regular Republicans met in convention the following month, Lincoln was aware of the need for winning the dissidents back to the party fold,” wrote historian Richard N. Current.1

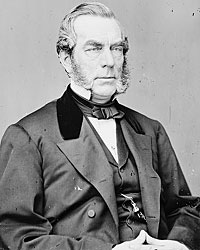

Both the Cleveland event and the Republican convention in Baltimore in early June took place days before the House of Representatives voted on the proposed 13th Amendment. Historian Roy P. Basler wrote: “Lincoln expected its defeat and saw that the proposal for complete abolition of slavery by amendment to the Constitution would be the key issue of his campaign for reelection. Even while the House was debating the resolution he called the chairman of the National Republican Committee, Senator Edwin D. Morgan of New York, to the White House, and asked him to make the keynote of his speech opening the convention a plea for the amendment, and to place the amendment as a plank in the Republican platform.”2 According to historian Richard N. Current, Mr. Lincoln told Morgan: “I want you to mention in your speech when you call the convention to order, as its keynote, and to put into the platform as the keystone, the amendment of the Constitution abolishing and prohibiting slavery forever.”3

Historian William Frank Zornow wrote: “New York Senator Edwin D. Morgan, chairman of the National Executive Committee, called the convention to order on June 7. The most significant remark in his opening address was an appeal for a constitutional amendment prohibiting slavery. A torrent of applause and cheering followed this assertion. Though Wendell Phillips later insisted that it was his abolitionists and the Cleveland convention which had given birth to the idea of a Thirteenth Amendment, it was the President himself who had suggested to Morgan several days before that this reference should be included in his opening message. Lincoln showed again his remarkable aptitude for accomplishing two objectives with one stroke; he placated the abolitionists and robbed the Fremont movement of its important remaining plank.”4 Lincoln biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay wrote that Morgan’s declaration “immediately found an echo in the speech of the temporary chairman, the Rev. Dr. Robert J. Breckinridge. The indorsement of the principle by the eminent Kentucky divine, not on the ground of party but on the high philosophy of true universal government and of genuine Christian religion, gave the announcement an interest and significance accorded to few planks in party platforms.”5

But, noted historian James Vorenberg, “Lincoln’s intervention in his party’s national convention was more an act of necessity than choice. He had to make sure that his party did not follow the example set in Cleveland too closely.” The Cleveland convention’s remarkable proposal for an amendment establishing ‘absolute equality’ was nearly identical to a measure proposed by Senator Charles Sumner and then defeated during the Senate debate of the antislavery amendment. Its egalitarian language no doubt went too far for most Republicans.”6

Historian Richard Current, wrote: “That platform included a plank stating that slavery was the cause of the rebellion, that the president’s proclamations had aimed ‘a death blow at this gigantic evil,’ and that a constitutional amendment was necessary to ‘terminate and forever prohibit’ it. Undoubtedly the delegates would have adopted such a plan whether or not Lincoln, through Senator Morgan, had urged it.”7 The platform read:

Resolved, That as slavery was the cause, and now constitutes the strength, of this rebellion, and as it must be, always and everywhere, hostile to the principles of republican government, justice and the national safety demand its utter and complete extirpation from the soil of the republic; and that while we uphold and maintain the acts and proclamations by which the government, in its own defense, has aimed a death-blow at this gigantic evil, we are in favor, furthermore, of such an amendment to the Constitution, to be made by the people in conformity with its provisions, as shall terminate and forever prohibit the existence of slavery within the limits of the jurisdiction of the United States.”8

Historian Joseph T. Wilson wrote of the brief Republican National Platform: “In the resolutions adopted, the fifth one of them related to Emancipation and the negro soldiers. It was endorsed by a very large majority of the voters. A writer in one of the magazines, prior to the election, thus reviews the resolutions”:

The fifth resolution commits us to the approval of two measures that have aroused the most various and strenuous opposition, the Proclamation of Emancipation and the use of negro troops. In reference to the first, it is to be remembered that it is a war measure. The express language of it is: ‘by virtue of the power in me vested as commander-in-chief of the army and navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and Government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion.’ Considered thus, the Proclamation is not merely defensible, but it is more; it is a proper and efficient means of weakening the rebellion which every person desiring its speedy overthrow must zealously and perforce uphold. Whether it is of any legal effect beyond the actual limits of our military lines, is a question that need not agitate us. In due time the supreme tribunal of the nation will be called to determine that, and to its decision the country will yield with all respect and loyalty. But in the mean time let the Proclamation go wherever the army goes, let it go wherever the navy secures a foothold on the outer border of the rebel territory, and let it summon to our aid the negroes who are truer to the Union than their disloyal masters; and when they have come to us and put their lives in our keeping, let us protect and defend them with the whole power of the nation. Is there anything unconstitutional in that? Thank God, there is not. And he who is willing to give back to slavery a single person who has heard the summons and come within our lines to obtain his freedom, he who would give up a single man, woman, or child, once thus actually freed, is not worthy the name of American. He may call himself Confederate, if he will.

Let it be remembered, also that the Proclamation has had a very important bearing upon our foreign relations. It evoked in behalf of our country that sympathy on the part of the people in Europe, whose is the only sympathy we can ever expect in our struggle to perpetuate free institutions. Possessing that sympathy, moreover, we have had an element in our favor which has kept the rules of europe in wholesome dread of interference. The Proclamation relieved us from the false position before attributed to us of fighting simply for national power. It placed us right in the eyes of the world, and transferred men’s sympathies from a confederacy fighting for independence as a means of establishing slavery, to a nation whose institutions mean constitutional liberty, and, when fairly wrought out, must end in universal freedom.”9

In responding to the delegation from the Union-Republican National Committee informing his of his renomination after the Convention, Mr. Lincoln emphasized the importance of the proposed 13th Amendment: “I will say now, however, [that] I approve the declaration in favor of so amending the Constitution as to prohibit slavery throughout the nation. When the people in revolt, with a hundred days of explicit notice, that they could, within those days, resume their allegiance, without the overthrow of their institution, and that they could not so resume it afterwards, elected to stand out, such [an] amendment of the Constitution as [is] now proposed, became a fitting, and necessary conclusion to the final success of the Union cause. Such alone can meet and cover all cavils. Now, the unconditional Union men, North and South, perceive its importance, and embrace it. In the joint names of Liberty and Union, let us labor to give it legal form, and practical effect.”10

Historian James M. McPherson wrote of the platform: “Emancipation had thus become an end as well as a means of Union victory; as Lincoln put it in his Gettysburg Address, the North fought from 1863 on for ‘a new birth of freedom.'”11

Footnotes

- Richard Nelson Current, The Lincoln Nobody Knows, p. 229.

- Roy P. Basler, A Touchstone for Greatness, p. 198.

- Richard Nelson Current, The Lincoln Nobody Knows, p. 229.

- William Frank Zornow, Lincoln & the Party Divided, p. 90-93.

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume X, p. 79.

- Charles M. Hubbard, editor, Lincoln Reshapes the Presidency, p. 161 (Michael Vorenberg, “A King’s Cure, A King’s Style: Lincoln, Leadership, and the Thirteenth Amendment”).

- Richard Nelson Current, The Lincoln Nobody Knows, p. 229.

- Ida M. Tarbell, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 215.

- Joseph T. Wilson, The Black Phalanx: African American Soldiers in the War of Independence, the War of 1812 & the Civil War, p. 107.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 381-382.

- Gabor S. Boritt, editor, Lincoln the War President, p. 55-57 (James M. McPherson, “Lincoln and the Strategy of Unconditional Surrender”).