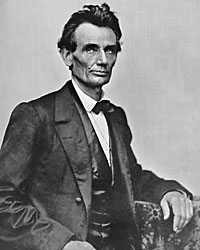

“The first impression of slavery which Abraham Lincoln received was in his childhood in Kentucky. His father and mother belonged to a small company of western abolitionists, who at the beginning of the century boldly denounced the institution as an iniquity. So great an evil did Thomas and Nancy Lincoln hold slavery that to escape it they were willing to leave their Kentucky home and move to a free State. Thus their boy’s first notion of the institution was that it was something to flee from, a thing so dreadful that it was one’s duty to go to pain and hardship to escape it,” wrote Lincoln biographer Ida Tarbell.1

Historian Louis A. Warren wrote: “A most disturbing and bitter controversy over the rights and wrongs of slavery was being waged in that part of Kentucky where the Lincolns lived. The record book of the South Fork Baptist Church, located within two miles of the Lincoln Sinking Spring home, shows that in 1808 fifteen members ‘went off from the church on account of slavery.’ At the time of Abraham Lincoln’s birth this church had closed its doors because its members could not meet in peace. Among its congregation were friends of the Lincolns and relatives of Nancy Lincoln….Thomas and Nancy affiliated with the Little Mount Church, a Separate Baptist congregation located about three miles from the Knob Creek farm. Its members were antislavery in sentiment.”2

Other biographers have suggested that slavery was less important than economics in the move. Historian Richard N. Current wrote: “Lincoln’s father was one of those frontiersmen who moved on to a farther frontier. There were more than a thousand slaves in the Hardin County of Abraham’s boyhood, but his parents owned none, and the Baptist church to which they belonged was strongly opposed to slaveholding. Whether because of religious conviction or because of resentment against the pretensions of wealthy slaveowners, Thomas Lincoln clearly disliked the institution when he chose to resettle in Indiana, which was about [to] enter the Union as a free state.”3

“As a boy Lincoln must have seen some slaves in Kentucky, for Hardin County reported 940 slaves in the census of 1810 in a total population of 7,531. But his family did not dwell among slaveholders, and Lincoln did not see large numbers of blacks until he made his first flatboat trip to New Orleans in 1828,” wrote Lowell H. Harrison in Lincoln of Kentucky.4

Biographer Ida Tarbell wrote: “In his new home in Indiana he heard the debate on slavery go on. The State he had moved into was in a territory made free forever by the ordinance of 1787, but there were still slaves and believers in slavery within its boundaries and it took many years to eradicate them. Close to his Indiana home lay Illinois and here the same struggle went on through all his boyhood. The lad was too thoughtful not to reflect on what he heard and read of the differences of opinions of slavery. By the time the Statutes of Indiana fell into his hands — some time before he was eighteen years old — he had gathered a large amount of practical information about the question which he was able then to weigh in the light of the great principles of Constitution, the ordinance of 1787, and the laws of Indiana, which he had begin to study with passionate earnestness.”5

Mr. Lincoln recognized the injurious impact of slavery on both whites and blacks. Historian Allen C. Guelzo wrote: “This slavery was what he experienced as a young man under his father, and he came to associate it with subsistence farming, and the Jeffersonian ideology that glorified it, with a backwards-looking mentality that conveniently froze wealthy landholders in places of power while offering the placebo of subsidy and protection (especially in the form of cheap land) to bungling yeomen in order to pacify their disgruntlements. ‘I used to be a slave,’ Lincoln said in an early speech; in fact, ‘we were all slaves on time or another.'” Guelzo added: “As late as 1859, Adlai Stevenson was puzzled by the way Lincoln ended a brief self-description — ‘no other marks or brands recollected’ — since this was the language ‘not infrequently employed in the South, especially Kentucky, for a notice of a ‘runaway slave.'”6

Mr. Lincoln had prepared a biography for his presidential campaign in 1860 which stated: “When he was nineteen, still residing in Indiana, he made his first trip upon a flat-boat to New-Orleans. He was hired hand merely; and he and a son of the owner, without other assistance, made the trip. The nature of part of the cargo-load, as it was called — made it necessary for them to linger and trade along the Sugar coast — and one night they were attacked by seven negroes with intent to kill and rob them. They were hurt in the melee, but succeeded in driving the negroes from the boat, and then ‘cut cable’ ‘weighed anchor’ and left.”7

Biographer Louis A. Warren wrote: “As soon as the boys entered the Mississippi, they began trading their cargo for cotton, tobacco, and sugar. All went peacefully for them until just below Baton Rouge. Here were the prosperous sugar plantations…extending down to the river. The story is that ‘a part of the cargo had been selected with special reference to the wants of the sugar plantations and the young adventurers were instructed to linger upon the sugar coast for the purpose of disposing it.'”8

Mr. Lincoln made a second trip down the Mississippi to New Orleans three years later in April to July 1831. Fellow rafter John Hanks recalled that when he and Mr. Lincoln arrived in New Orleans, “There it was we Saw Negroes Chained — maltreated — whipt & scourged[.] Lincoln Saw it – his heart bled – Said nothing much — was silent from feeling — was Sad — looked bad — felt bad — was thoughtful & abstracted — I Can say Knowingly that it was on this trip that he formed his opinions of Slavery: it ran its iron in him then & there — May 1831.”9

“In New Orleans, for the first time Lincoln beheld the true horrors of human slavery,” wrote Mr. Lincoln’s legal colleague, William H. Herndon. “Agains[t] this inhumanity his sense of right and justice rebelled, and his mind and conscience were awaked to a realization of what he had often heard and read.”10 Herndon wrote from Hanks’ memories: “One morning in their rambles over the city the trio passed a slave auction. A vigorous and comely mulatto girl was being sold. She underwent a through examination at the hands of the bidders; they pinched her flesh and made her trot up and down the room like a horse, to show how she moved, and in order, as the auctioneer said, that ‘bidders might satisfy themselves’ whether the article they were offering to buy was sound or not. The whole thing was so revolting that Lincoln moved away from the scene with a deep feeling of ‘unconquerable hate.’ Bidding his companions follow him he said, ‘By God, boys, let’s get away from this. If ever I get a chance to hit that thing [meaning slavery], I’ll hit it hard.” This incident was furnished me in 1865, by John Hanks. I have also heard Mr. Lincoln refer to it himself.”11

Historian Richard Nelson Current threw doubts on this story: “John Hanks told the anecdote to Herndon in 1865. Hanks had been one of Lincoln’s fellow voyagers of the flatboat, but he did not go all the way with the others to New Orleans, so he could not have seen with his own eyes what happened at the slave auction he later described. Herndon said he also heard the story from Lincoln himself. In the account of the journey he gave in his autobiography of 1860, however, Lincoln made no mention of slaves or the slave trade (though of course he intended the autobiography for campaign purposes and could not have been so indiscreet as to emphasize any abolitionist convictions). In the autobiography, he also spoke of a previous trip to New Orleans. With regard to this trip, he said nothing about slaves but did refer to Negroes, recalling that he and his own companion ‘were attacked by seven Negroes with intent to kill and rob them’ and were ‘hurt some in the melee, but succeeded in driving the Negroes from the boat.'”12

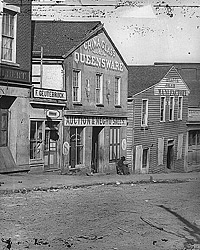

Coming back to Illinois from New Orleans, Mr. Lincoln returned to New Salem where there was a store owned by Dennis Offut, the merchant who has sponsored the New Orleans trek. Mr. Lincoln had been offered a position as a clerk in Offut’s store. Historian Kenneth J. Winkle wrote: “When Lincoln settled in New Salem, thirty-eight African Americans were living in Sangamon County out of a total population of more than twelve thousand. Most of them, just over two-thirds, were free. In the entire county, only on African American, Lucy Roundtree, headed an independent household. The remaining free blacks were servants living in white families. Six residents of the county, including John Todd, the patriarch of the Todd family in Springfield, owned slaves.”13

Lincoln Contemporary Daniel Green Burner recalled: “I often heard Lincoln speak about slavery while we were together in New Salem, and he was always opposed to it. “I did not imagine then that Lincoln had a great future before him, but I heard others say that they believed he would some time be Governor of Illinois. Still I knew he was smart. We had a debating society that met in the schoolhouse occasionally, and Lincoln was always keen for such entertainment. He was a good debater. He couldn’t be beat by any one in those parts. He was a natural talker. It was not so much in his studying a subject as that the argument seemed to come right out of him without study or long preparation. Everybody liked to hear him. Some of those who argued against him were Dave Rutledge, Bill Green, a particular friend of Lincoln, and Jackson Graham. I didn’t go very often for to tell the truth I didn’t take much stock in such doings.”14

In Springfield, there was a small but growing community of free blacks, led by Mr. Lincoln’s friend and barber, William Florville, Historian Ken Winkle wrote: “The presence of African Americans, both slave and free, provoked a wide range of responses among white Springfielders. At one extreme, the demand for labor drew some of them into the underground market for slaves.” Added Winkle. “At the other extreme, whites sometimes worked to set Springfield’s slaves free….Somewhere between these two extremes, most Springfielders neither owned nor freed slaves.”15 Springfield carpenter John E. Roll said that Mr. Lincoln once said in a political speech: “There is my old friend John Roll. He used to be a slave, but he has made himself free, and I used to be a slave, and now I am so free that they let me practice law.”16

Mr. Lincoln’s attitude may have been shaped by his upbringing. “As a youth, Lincoln was like a slave to his father, who insisted that his son not only labor on the family farm but also that he work for neighbors and then turn over every penny that he had earned,” noted historian Michael Burlingame.17 “He so emphatically deplored the way that owners robbed slaves of their rightful earnings because, as Gabor Boritt suggests, Lincoln ‘sympathized and, to a degree, identified with the downtrodden black man.'”18

Historian Allen C. Guelzo wrote: that “the Lincolns employed at least two free African-American women, Maria Vance and Ruth Stanton, as domestic help. The house that Lincoln bought from Charles Dresser (who also held an ‘indentured servant’ named Hepsey at the time of the sale) was in the middle of a neighborhood that had twenty-one African-Americans, in conditions ranging from free to slave, living in it.”19 According to historian Kenneth J. Winkle, “The Lincolns’ personal relations with free blacks were always respectful, yet they interacted with them only as the employers of servants. At least four African Americans provided domestic help for the Lincolns.”20

On several occasions Mr. or Mrs. Lincoln returned to Lexington, Kentucky where Mrs. Lincoln’s relatives lived. Lowell H. Harrison wrote in Lincoln of Kentucky: “After his marriage to Mary Todd, Lincoln also saw a benign form of slavery when he visited the Lexington home of his in-laws. Chaney was the treasured cook, Mammy Sally had charge of the nursery, Nelson supervised the stables except when he was called upon to concoct mint juleps for special guests. But Lexington also had slave markets, and there Lincoln witnessed a quite different aspect of the peculiar institution from the one he saw in the Todd home.”21 Mr. Lincoln and his family visited Lexington in November 1847 on their way to Washington. Niece Katherine Helm wrote: “The whole family stood near the front door with welcoming arms and, in true patriarchal style, the colored contingent filled the rear of the hall to shake hands with the long absent one and ‘make a miration’ over the babies.”22

Lincoln chronicler Paul Findley wrote: “In the middle of the public square in Lexington stood a slave auction block. Nearby, a public whipping post reminded the slaves of the punishment they would receive if they overstepped boundaries — if they failed to ‘stay in their place.’ News articles in the Lexington papers revealed the deep but submerged hostility between slave and owner. A young slave girl named Cassily, for example, had been indicted for mixing an ounce of ground glass with the gravy for dinner and serving it to her master. A few days after Lincoln arrived in Lexington, the death of Mrs. Elizabeth Warren received widespread publicity. Most of the town thought she had been murdered by slaves. Reports of similar incidents in other towns appeared frequently in the newspapers Lincoln read during his Lexington vacation.”23 This sojourn was Mr. Lincoln’s first extensive experience with slavery.

Mr. Lincoln’s attitudes toward slavery were closely connected to his ideas about work, wealth and justice. Friend and political colleague Joseph Gillespie wrote: “Mr. Lincolns sense of justice was intensely strong[.] It was to this mainly that his hatred of slavery may be attributed[.] He abhorred the institution[.] It was about the only public question on which he would become excited[.] I recollect meeting with him once at Shelbyville when he remarked that something must be done or slavery would overrun the whole country[.] He said there were about 600,000 non slave holding whites in Kentucky to about 33,000 slave holders[.] That in the convention then recently held it was expected that the delegates would represent these classes about in proportion to their respective numbers but when the convention assembled there was not a single representative of the non slaveholding class[.] Every one was in the interest of the slaveholders and said he this thing is spreading like wild fire over the Country[.] In a few years we will be ready to accept the institution in Illinois and the whole country will adopt it[.] I asked him to what he attributed the change that was going on in public opinion. He said he had put that question to a Kentuckian shortly before who answered by saying — you might have any amount of land, money in your pocket or bank stock and while travelling around no body would be any the wiser but if you had a darkey trudging at your heels every body would see him & know that you owned slaves — It is the most glittering ostentatious & displaying property in the world and now says he if a young man goes courting the only inquiry is how many negroes he or she owns and not what other property they may have[.] The love for Slavery property was swallowing up every other mercenary passion[.] Its ownership betokened not only the possession of wealth but indicated the gentleman of leisure who as was above and scorned labour[.] These things Mr[.] Lincoln regarded as highly seductive to the thoughtless and giddy headed young men who looked upon work as vulgar and ungentlemanly[.] Mr Lincoln was really excited and said with great earnestness that this spirit ought to be met and if possible checked[.] That slavery was a great & crying injustice an enormous national crime and that we could not expect to escape punishment for it[.]”24

Footnotes

- Ida M. Tarbell, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume I, p. 220.

- Louis A. Warren, Lincoln’s Youth, Indiana Years, p. 13.

- Richard Nelson Current, Speaking of Abraham Lincoln, p. 162.

- Lowell H. Harrison, Lincoln of Kentucky, p. 81.

- Ida M. Tarbell, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume I, p. 220-221.

- Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, p. 121.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 60-67.

- Louis A. Warren, Lincoln’s Youth, Indiana Years, p. 184.

- Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, editor, Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, p. 457 (William H. Herndon interview with John Hanks, ca. 1865-1866. Hanks’ account may be questioned since Mr. Lincoln said Hanks traveled only as far as St. Louis.).

- William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 63.

- William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 63-64.

- Richard Nelson Current, Speaking of Abraham Lincoln: The Man and His Meaning for Our Times, p. 19.

- Kenneth J. Winkle, The Young Eagle: The Rise of Abraham Lincoln, p. 251.

- Daniel Green Burner, “Lincoln and The Burners at New Salem”, The Many Faces of Lincoln, p. 191.

- Kenneth J. Winkle, The Young Eagle: The Rise of Abraham Lincoln, p. 252.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 383 (John E. Roll, Chicago Times-Herald, August 25, 1895).

- Michael Burlingame, The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, p. 37.

- Michael Burlingame, The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln, p. 35.

- Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, p. 125.

- Kenneth J. Winkle, The Young Eagle: The Rise of Abraham Lincoln, p. 266.

- Lowell H. Harrison, Lincoln of Kentucky, p. 82.

- Katherine Helm, Mary: Wife of Lincoln, p. 99-100.

- Paul Findley, A. Lincoln, The Crucible of Congress: The Years Which Forged His Greatness, p. 66.

- Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, editor, Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, p. 183 (Letter from Joseph Gillespie to William H. Herndon, January 31, 1866).

Visit

Joseph Gillespie (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

John Hanks (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Herndon (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Mary Todd Lincoln (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Joshua F. Speed (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)