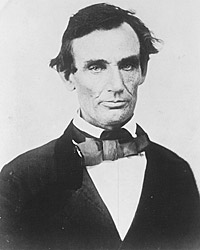

In 1854, Mr. Lincoln avoided meeting with the organizers of the new Republican Party. In 1856, Mr. Lincoln was maneuvered into taking a leadership role by his law partner, William H. Herndon. Herndon wrote in his biography of Mr. Lincoln: “Finding himself drifting about with the disorganized elements that floated together after the angry political waters had subsided, it became apparent to Lincoln that if he expected to figure as a leader he must take a stand himself. Mere hatred of slavery and opposition to the injustice of the Kansas-Nebraska legislation were not all that was required of him. He must be a Democrat, Abolitionist, Know-Nothing or Republican, float forever about in the great political sea without compass, rudder or sail. At length he declared himself. Believing the times were ripe for more advanced movements, in the spring of 1856 I drew up a paper for friends of freedom to sign, calling for the forthcoming Republican state convention in Bloomington. The paper was freely circulated, and generously signed. Lincoln was absent at the time; and, believing I knew what his feelings and judgment on the vital questions of the hour were, I took the liberty to sign his name to the call. The whole was then published in the Springfield Journal. No sooner had it appeared than John T. Stuart, who, with others, was endeavoring to retard Lincoln in his advanced movements, rushed into our office, and excitedly asked ‘if Lincoln had signed that Abolition call in the Journal. I answered in the negative, adding that I had signed his name myself. To the question, ‘Did Lincoln authorize you to sign it?’ I returned an emphatic ‘No.’ ‘Then,’ exclaimed the startled and indignant Stuart, ‘you have ruined him.’ But I was by no means alarmed at what others deemed hasty and inconsiderate action. I thought I understood Lincoln thoroughly, but in order to vindicate myself if assailed, I immediately sat down after Stuart had rushed out of the office, and wrote Lincoln, who was then in Tazewell county, attending court, a brief account of what I had done and how much stir it was creating in the ranks of his conservative friends. If he approved or disapproved my course, I asked him to write or telegraph me at once. In a brief time came his answer: ‘All right. Go ahead. Will meet you radicals and all.’ Stuart subsided, and the conservative spirits who hovered around Springfield no longer held control of the political fortunes of Abraham Lincoln.”1

On the evening of May 28, 1856 the night before the first Illinois Republican State Convention, some extemporaneous speeches were made in Bloomington. According to the anti-Lincoln Illinois State Register:

In the evening a meeting was held in front of Pike House, and several speeches were made. The speakers were Lincoln, [Elihu] Washburne, [John] Palmer, [Leonard] Swett, [Owen] Lovejoy and [John] Wentworth.

Lincoln led off; said he didn’t expect to make a speech then; that he had prepared himself for one, but ’twas not suitable at that time, but that after awhile he would make them a most excellent one. Notwithstanding, he kept on speaking, told his old story about the fence (meaning Missouri restriction) being torn down and the cattle-eating up the crops, then talked about the outrages in Kansas; said a man couldn’t think, dream or breathe of a free state there, but what he was kicked, cuffed, shot down and hung; he then got very pathetic over poor [Mark] Delahay and Tom Shoemaker. By the way, Mr. Register, I wonder if any one in this community knows Delahay and Shoemaker; if so we pass them and also Lincoln’s speech, and come next to that of [Elihu’ Washburne, which was celebrated only for the vehement and uproarious manner with which it was delivered.2

The next day, according to Lincoln biographer William H. Herndon, “The Republican Party came into existence in Illinois.” Lincoln biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay wrote: “Minor and past differences were therefore generously postponed or waived in favor of a hearty coalition on the single dominant question. A most notable gathering of the clans was the result. About one-fourth of the counties sent regularly chosen delegates; the rest were volunteers. In spirit and enthusiasm it was rather a mass meeting than a convention; but every man present was in some sort a leader in his own locality. The assemblage was much more representative than similar bodies gathered by the ordinary caucus machinery. It was an earnest and determined council of five or six hundred cool, sagacious, independent thinkers, called together by a great public exigency, led and directed by the first minds of the State. Not only did it show a brilliant array of eminent names, but a remarkable contrast of former antagonisms: Whigs, Democrats, Free-Soilers, Know-Nothings, Abolitionists; Norman B. Judd, Richard Yates, Ebenezer Peck, Leonard Swett, Lyman Trubull, David Davis, Owen Lovejoy, Orville H. Browning, Ichabod Codding, Archibald Williams, and many more.”3

Herndon noted: “The firm of Lincoln and Herndon was represented by both members in person. The gallant William H. Bissell, who had ridden at the head of the Second Illinois Regiment at the battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican war, was nominated as governor. The convention adopted a platform ringing with strong Anti-Nebraska sentiments, and then and there gave the Republican party its official christening. The business of the convention being over, Mr. Lincoln, in response to repeated calls, came forward and delivered a speech of such earnestness and power that no one who heard it will ever forget the effect it produced. In referring to this speech some years ago I used the following rather graphic language: ‘I have heard or read all of Mr. Lincoln’s great speeches, and I give it as my opinion that the Bloomington speech was the grand effort of his life. Heretofore he had simply argued the slavery question on ground of policy,– the statesman’s grounds,– never reaching the question of the radical and the eternal right. Now he was newly baptized and freshly born; he had the fervor of a new convert; the smothered flame broke out; enthusiasm unusual to him blazed up; his eyes were aglow with an inspiration; he felt justice; his heart was alive to the right; his sympathies, remarkably deep for him, burst forth, and he stood before the throne of the eternal Right. His speech was full of fire and energy and force: it was logic; it was pathos; it was enthusiasm; it was justice, equity, truth, and right set ablaze by the divine fires of a soul maddened by the wrong; it was hard, heavy, knotty, gnarly, backed with wrath. I attempted for about fifteen minutes as was usual with me then to take notes, but at the end of that time I threw pen and paper away and lived only in the inspiration of the hour. If Mr. Lincoln was six feet, four inches high usually, at Bloomington that day he was seven feet, and inspired at that. From that day to the day of his death he stood firm in the right.”4

Contemporary observer William H. Porter, then 17, later wrote: “When the convention speeches finished about 5:30 o’clock people began calling for Lincoln. From his seat in the back of the house, near where I sat, Lincoln got up and said he believed he would talk from where he was, if nobody objected. But everybody shouted for him to take the platform. All heads turned to the back of Major’s Hall, when Lincoln’s long frame unlimbered itself. Cheers shook the walls as he elbowed his way down the aisle.”5

Lincoln biographer William E. Barton wrote: “There stood Lincoln in the forefront, erect, tall, and majestic in appearance, hurling thunderbolts at the foes of freedom, while the great convention roared its endorsement! I never witnessed such a scene before or since. As he descried the aims and aggressions of the unappeasable slaveholders and the servility of their Northern allies as illustrated by the perfidous repeal of the Missouri Compromise two years previously, and their grasping after the rich prairies of Kansas and Nebraska, to blight them with slavery and to deprive free labor of this rich inheritance, and exhorted the friends of freedom to resist them to death, the convention went fairly wild. It paralleled or exceeded the scene in the Revolutionary Virginia convention of eight-one years before, when Patrick Henry invoked death if liberty could not be preserved, and said, ‘After all we must fight.’ Strange, too, that this same man received death a few years afterwards while conferring freedom on the slave race and preserving the American Union from dismemberment.”6

According to young William H. Porter, “the tall man in black told us about the aims of the new party they were organizing that day. I’ll say now that I learned more during that next hour and a half, about what was the best for the United States, than I’d learned in all my life before. Lincoln explained about the things Washington and his soldiers believed in, to prove what the Declaration of Independence meant. Gradually, he began to talk faster. His tall frame rose and fell. He’d fling his arms out at us in forceful gestures. Closer and closer, I noticed him peering into the faces of his audience.”7

Another observer, Kansas abolitionist James S. Emery, later recalled that “his chief contention all through it was that Kansas must come in free, not slave, he said he did not want to meddle with slavery where it existed and that he was in favor of a reasonable fugitive slave law.” Emery wrote that Mr. Lincoln “was at his best, and the made insolence of the slave power as at that time exhibited before the country furnished plenty of material for his unsparing logic to effectively deal with before a popular audience.”8 Lincoln biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay wrote: “The spell of the hour was visibly upon him; and holding his audience in rapt attention, he closed in a brilliant peroration with an appeal to the people to join the Republican standard, to

Come as the winds come, when forests are rended;

Come as the waves come, when navies are stranded.9

The text of what Mr. Lincoln actually said has remained a mystery. Historian Paul Angle wrote: “Only one contemporary report of Lincoln’s address is known to exist, and that was published in the Alton Courier for June 5, 1856.” The newspaper reported: “Abraham Lincoln, of Sangamon, came upon the platform amid deafening applause. He enumerated the pressing reasons of the present movement. He was here ready to fuse with anyone who would unite with him to oppose slave power; spoke of the bugbear disunion which was so vaguely threatened. It was to be remembered that the Union must be preserved in the purity of its principles as well as in the integrity of its territorial parts. It must be ‘Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.’ The sentiment in favor of white slavery now prevailed in all the slave state papers, except those of Kentucky, Tennessee and Missouri and Maryland. Such was the progress of the National Democracy. Douglas once claimed against him that Democracy favored more than his principles, the individual rights of man. Was it not strange that he must stand there now to defend those rights against their former eulogist? The Black Democracy were endeavoring to cite Henry Clay to reconcile old Whigs to their doctrine, and repaid them with the very cheap compliment of National Whigs.”10

Robert S. Harper wrote in Lincoln and the Press: “The Bloomington speech was ‘lost’ because Lincoln and the editors wished it to be ‘lost.’ The opposition press was not represented at the convention. In a day of purely political editing, it was the custom for editors to ignore what the other party was doing so far as factual reporting was concerned. The Bloomington convention was guided by a radical spirit; Kansas antislavery agitators had been imported for the occasion. Lincoln gave them the talk they wanted to hear.”11

Indeed, Chicago Tribune editor Joseph Medill recalled: “My belief is, that after Mr. Lincoln cooled down, he was rather pleased that his speech had not been reported, as it was too radical in expression on the slavery question for the digestion of central and southern Illinois at that time, and that he preferred to let it stand as a remembrance in the minds of his audience. But be that as it may, the effect of it was such on his hearers that he bounded to the leadership of the new Republican party of Illinois, and no man afterwards ever thought of disputing that position with him. On that occasion he planted the seed which germinated into a Presidential candidacy and that gave him the nomination over [William H.] Seward at the Chicago convention in 1860, which placed him in the Presidential chair, there to complete his predestined work, of destroying slavery and making freedom universal, but yielding his life as a sacrifice for the glorious deeds.'”12 Mr. Lincoln’s more conservative friend, T. Lyle Dickey, recalled:

“In that speech Mr[.] Lincoln distinctly proclaimed it as his opinion that our Government Could not last– part slave & part free -: that either Slavery must be abolished every where– or made equally lawful in all the states or the Union would be dismembered. I Can not be mistaken about this– for I was very sorry to hear him express an opinion which I regarded as erroneous & very dangerouss [sic]– After the Meeting was over– Mr[.] Lincoln & I returned to Pike House– where we occupied the Same room– Immediately on reaching the room I said to Mr [.] Lincoln– ‘What in God’s name could induce you to promulgate such an opinion’ Mr [.] Lincoln replied familiarly– ‘Upon my soul Dickey I think it is true’– I reasoned to show it was not a correct opinion– He argued strenuously that the opinion was a sound one– At length I said to Mr[.] Lincoln– ‘Suppose you are right in this opinion, & that our Government Can not last part free & part slave– What good is to be accomplished by inculcating that opinion (or truth if you please) in the minds of the People?– After a moment of silence & apparent reflection Mr[.] Lincoln Said– “I do not see as there is any good to be accomplished [by] the dissemination of the doctrine.” To which replied– ‘I can see much harm which it may do[.]” “You convince the whole people of this– & you necessarily make Abolitionists of all the People of the North & Slavery proponents of all South– & you precipitate a struggle which may end in disunion– The teaching of the opinion it seems to me tends to hasten the calamity’ After some minutes reflection M[.] Lincoln rose & approached me extending his right hand to take mine & Said–

“I don’t see any necessity for teaching this doctrine– & I don’t Know but it might do harm”– At all events from respect for your judgment, Dickey, I[‘]ll promise you I wont say so again during this Campaign”– We shook hands upon it & the subject was dropped– I heard no more of this time [type] of thought from Mr[.] Lincoln until the year of 1858– when he proclaimed it in his famous Speech at Springfield– at the Opening of that years Canvass.13

Mr. Lincoln took an active role in the Republican campaigns for Governor and President that year. His speaking invitations became so numerous that he complained to Iowa Governor James W. Grimes that he was “plagued” by his request to speak in Iowa.”14 At the Republican National Convention in Philadelphia, he was nominated for but lost the nomination for Vice President on a ticket with John C. Frémont. In his campaign speeches, Mr. Lincoln stressed Republicans’ commitment to the Union. The Galena Weekly North-Western Gazette reported: that: “Abraham Lincoln hits the nail on the head every time, and in this instance it will be seen, he has driven it entirely out of sight,— if we succeed as well as we anticipate in re-producing from memory his argument in relation to ‘Disunion.'” The newspaper reported:

Mr. Lincoln was addressing himself to the opponents of Fremont and the Republican party, and had referred to the charge of ‘sectionalism,’ and then spoke something as follows in relation to another charge, and said:

‘You further charge us with being Disunionists. If you mean that it is our aim to dissolve the Union, for myself I answer, that is untrue; for those who act with me I answer, that it is untrue. Have you heard us assert that as our aim? Do you really believe that such is our aim? Do you find it in our platform, our speeches, our conversation, or anywhere? If not, withdraw the charge.15

Mary Todd Lincoln wrote her half-sister after Frémont’s defeat in the 1856 election: “Altho’ Mr L— is, or was a Fremont man, you must not include him with so many of those, who belong to that party, an Abolitionist. In principle he is far from it— All he desires is, that slavery, shall not be extended, let it remain, where it is– My weak woman’s heart was too Southern in feeling, to sympathise with any but Fillmore, I have always been a great admirer of his, he made so good a President & is so just a man & feels the necessity of keeping foreigners, within bounds. If some of you Kentuckians, had to deal with the ‘wild Irish,’ as we housekeepers are sometimes called upon to do, the south would certainly elect Mr Fillmore next time…”16

Footnotes

- William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 311-312.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 340-341 (Speech at Bloomington, May 28, 1856).

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume II, p. 28.

- William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 312-313.

- Elwell Crissey, Lincoln’s Lost Speech, p. 214.

- William E. Barton, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, Volume I, p. 358.

- Elwell Crissey, Lincoln’s Lost Speech, p. 214.

- Elwell Crissey, Lincoln’s Lost Speech, p. 217-218.

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume II, p. 30.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume.II, p. 341 (Speech at Bloomington, May 29, 1856).

- Robert S. Harper, Lincoln and the Press, p. 17.

- William E. Lilly, Set My People Free, p. 197-198.

- Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, editor, Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, p. 504-505 (Letter from T. Lyle Dickey, December 8, 1866).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 348 (Letter to James W. Grimes, July 12, 1856).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume II, p. 353-354 (Speech in Galena, July 23, 1856).

- Justin G. Turner and Linda Levitt Turner, editor, Mary Todd Lincoln Her Life & Letters, p. 36-38 (Excerpt of Letter to Emilie Todd Helm, November 23, 1856).