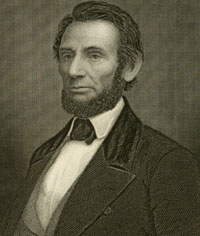

The right to vote was eventually guaranteed in the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution. But it was not a right that most Americans recognized before or during the Civil War. The question of suffrage for newly freed blacks became an important part of the President Lincoln’s reconstruction program. “Had the issues of Reconstruction and black ballots not become intertwined during the middle of the Civil War, it is far from clear that the suffrage issue would have become a matter for widespread political debate by early 1865,” wrote historian Robert Cook.1 Those issues have been generating debate among historians ever since. President Lincoln’s thinking was revealed in a letter he wrote General James A. Wadsworth, an abolitionist Republican from New York, in early January 1864:

You desire to know, in the event of our complete success in the field, the same being followed by a loyal and cheerful submission on the part of the South, if universal amnesty should not be accompanied with universal suffrage.

Now, since you know my private inclinations as to what terms should be granted to the South in the contingency mentioned, I will here add, that if our success should thus be realized, followed by such desired results, I cannot see, if universal amnesty is granted, how, under the circumstances, I can avoid exacting in return universal suffrage, or, at least, suffrage on the basis of intelligence and military service.

How to better the condition of the colored race has long been a study which has attracted my serious and careful attention; hence I think I am clear and decided as to what course I shall pursue in the premises, regarding it a religious duty, as the nation’s guardian of these people, who have so heroically vindicated their manhood on the battle-field, where, in assisting to save the life of the Republic, they have demonstrated in blood their right to the ballot, which is but the humane protection of the flag they have so fearlessly defended.

The restoration of the Rebel States to the Union must rest upon the principle of civil and political equality of both races; and it must be sealed by general amnesty.2

This had not always been Mr. Lincoln’s position. Indeed, in his September 1859 speech in Colombus Ohio, he specifically denied advocating suffrage for blacks. “Mr. Lincoln did not intend to force negro suffrage upon the people in the rebel States,” later wrote Lincoln friend Ward Hill Lamon later. ‘Doubtless, he desired that the negroes should have the right of suffrage, but he expected and hoped that the people would confer the right of their own will. He knew that if this right were forced upon them, it could not or would not be exercised in peace. He realized in advance that the experiment of legislative equality was one fraught with difficulties and dangers, not only to the well-being of the negro, but to the peace of society.”3

A leading advocate for black suffrage was black abolitionist Frederick Douglass “In Douglass’ early Reconstruction thought, he gave great importance to black suffrage. He revived the demand for the franchise in 1863 and, defending blacks against all claims that they were not ready to vote, called for immediate and unconditional suffrage,” wrote historian David W. Blight. Douglass maintained that if a black “knows enough to take up arms in defense of this Government…., he knows enough to vote.”4 In October 1864, Douglass prepared an “Address to the People of the United States” which was adopted by a National Convention of Colored Citizens of the United States meeting in Syracuse, New York:

“We want the elective franchise in all the States now in the Union, and the same in all such States as may come into the Union hereafter. We believe that the highest welfare of this great country will be found in erasing from its statute-books all enactments discriminating in favor of or against any class of its people, and by establishing one law for the white and colored people alike…

Formerly our petitions for the elective franchise were met and denied upon the ground, that, while colored men were protected in person and property, they were not required to perform military duty…But now even this frivolous…apology for excluding us from the ballot-box is entirely swept away. Two hundred thousand colored men, according to a recent statement of President Lincoln, are now in the service, upon field and flood, in the army and the navy of the United States; and every day adds to their number…

In a republican country, where general suffrage is the rule, personal liberty, the right to testify in courts of law, the right to hold, buy and sell property, become mere privileges, held at the option of others, where we are excepted from the general political liberty…

The possession of that right [the ballot] is the keystone to the arch of human liberty…We are men, and want to be as free in our native country as other men.5

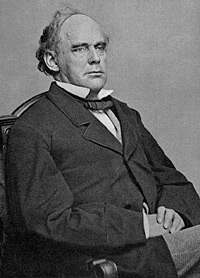

President Lincoln requested Attorney General Edward Bates to review questions regarding black voting rights in the late fall of 1864. Bates biographer Marvin Cain wrote: “In his opinion, rendered on November 29, Bates noted that there was no standard for citizenship, least of all for the right of suffrage. American citizenship, he argued, ‘does not necessarily depend upon nor coexist with the legal capacity to hold office and the right of suffrage.’ A citizen, therefore, had only to be a member of a political community, whether he was born white or black. Even a slave might be accorded the status of citizenship, since such recognition did not mean that a person had ‘all the rights, privileges and immunities’ normally granted a voter. It could be, bates concluded, that ‘a child in a cradle, viewed as a citizen merely, is the equal of his father in the Senate.’ He decided, therefore, that the Negro commanding the vessel possessed the privileges of citizenship.”6

Historian Robert Cook wrote: “Douglass’s effortless shift from citizenship to suffrage was a natural one for an expert political agitator, particularly a black one, to make but it was probably based on a wilful misreading of the Attorney General’s opinion which had been delivered on 29 November 1862. In that decision Edward Bates, a conservative Republican from Missouri, had rejected Chief Justice Taney’s ruling in the Dred Scott case that blacks could not be considered citizens of the United States. Asserting that ancient and contemporary authorities supported a broad definition of national citizenship, Bates undermined Taney’s decision by contending, firstly, that all free persons born in the United States were citizens of the United States and, secondly, that the Court’s controversial definition of citizenship was largely ‘dehors the record’ and therefore of no authority as a legal decision. While Bates emphasized that he did not concur with the Aristotelian notion that political rights flowed naturally from citizenship…his ruling made the citizenship portion of the Dred Scott decision a dead letter.”7

The suffrage issue had to be considered in the larger context of reconstruction policy. Historian Don E. Fehrenbacher wrote: “Lincoln’s program of reconstruction can perhaps be understood best as the product of reactive leadership – that is, as a series of calculated responses to changing military and political conditions. In the beginning, it was a wartime program, intended primarily to facilitate military victory and the progress of emancipation. Lincoln wanted to detach Southerners from their Confederate allegiance and to set in motion a process of abolition by state action. And fearing that the fundamental purposes of the war were at risk in the approaching electoral votes that would undoubtedly come to him from any Confederate states fully restored to the Union. During the early stages of the program, it should be noted, Lincoln plainly conceived of reconstruction as a task for white Southerners working in cooperation with army commanders. Such was the import of his ten-percent plan, announced in December 1863, and his subsequent letter to [Louisiana Governor Michael] Hahn raising the question of black suffrage in Louisiana was more of an exception than a new departure.”8

Mr. Lincoln thought reconstruction was an executive responsibility while many Radical Republican members of Congress jealously guarded their own prerogatives. Historian Richard H. Sewall wrote: “From the beginning, in fact, there had been strong opposition from many quarters to Lincoln’s design for Reconstruction. Abolitionists pounced on the president’s ‘wrong-headed’ toleration of apprenticeship schemes, denounced his failure to insist upon black suffrage, and questioned the trust he placed in Southern Unionists. In the states being reconstructed, radical Unionists themselves criticized Lincoln and his local followers for stopping short of universal suffrage and neglecting other safeguards against a restoration of planter dominance. Louisiana’s free Negroes, especially those in New Orleans who had for generations formed a sizable, prosperous, and literate part of the community, were particularly critical of their disfranchisement. The black New Orleans Tribune went still further, adding to manhood suffrage a call for property confiscation and land reform. ‘It is enough for the republic to spare the life of the rebels, without restoring to them their plantations and palaces,’ the Tribune editorialized. ‘The whole world will applaud the wisdom of the principle: amnesty for the persons, no amnesty for the property.'”9 Even as Mr. Lincoln was preparing the final draft for the Emancipation Proclamation, his conflict with Congress surfaced in an unusual example of presidential irritation. According to John Palmer Usher, there was a discussion in the Cabinet about the impact on Louisiana and congressional objection to seating representatives from that state: “”There it is, sir. I am to be bullied by Congress, am I? If I do I’ll be durned.”10

There were contending factions both in Washington, D.C. and inside the state. Their interests were disparate. Historian Richard N. Current wrote that President Lincoln: “hoped that the southern states, as they restored loyal governments, would make provisions for the elevation of the Negroes. In 1864 Lincoln wrote to the new governor of the ‘free state’ of Louisiana to suggest that the vote be given immediately to those Negro men who were educated, owned property, or had served in the Union army. But Lincoln did not feel that he could properly dictate to the states on matters of social or political rights. Again he was guided and curbed by his concepts of the Constitution and the Union.”11

Historian Philips S. Paludan wrote: “The problem for Lincoln and for those people who sought to bring the Bayou State back into the Union was to keep this fragile coalition together. Adding to the complexity was the problem that increasing rights for blacks alienated growing numbers of whites. In an ideal world white Unionists would take Lincoln’s journey – learning that expanding rights for blacks was imperative to save the Union and was legitimate on more grounds….But Louisiana was hardly an ideal world. Powerful, abiding prejudice and the environment of war meant that coercion would be necessary to promote education, and some would never learn.”12

Louisiana was a test case for presidential reconstruction – and black suffrage. “The gens de couleur were obviously qualified voters; their education, wealth, and other accomplishments argued for full equality,” wrote historian Philip S. Paludan. “They had been organizing and campaigning for it since the Unionists had take over the government in mid-1862. Yet not even the most liberal Unionists would support officially giving them the vote. The blacks could attend meetings that advocated full emancipation, they could listen to and join private discussions and hear an occasional speech about their rights, but the white Unionists would not publicly support their right to vote.”13

Historian Eric Foner wrote: “In New Orleans lived the largest free black community of the Deep South. The wealth, social standing, education, and unique history of this community set it apart not only from the slaves, but from most other free persons of color. The majority were the light-skinned descendants of unions between French settlers and black women or of wealthy mulatto emigrants from Haiti, and identified more fully with European that American culture. Many spoke only French and educated their children at private academies in New Orleans, or in Paris. Although barred from the suffrage, they enjoyed far more rights than free blacks in other states, including the right to travel without restriction and testify in court against whites, and had a self-conscious military tradition dating back to their participation under Andrew Jackson in the Battle of New Orleans.”14

Early in the War, the state’s freed blacks formed a Louisiana Equal Rights League. Historian James M. McPherson wrote “New Orleans blacks decided to take their case directly to the national government. On January 5, 1864, they drew up a petition for the right to vote and addressed it to both President Lincoln and Congress. It was signed by more than 1,000 men, 27 of whom had fought under Andrew Jackson against the British at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815. Many other signers had fought for the Union army in the Civil War. Jean Baptiste Roundanez and Arnold Bertonneau carried the petition to Washington.” McPherson noted: “President Lincoln was impressed. The following day he wrote the governor of Louisiana, who was preparing for the constitutional convention:15

Louisiana was also a test case for Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase’s own policies on reconstruction. Chase had become a prime advocate for black suffrage. Chase biographer Albert Bushnell Hart wrote: “It took a long time for him clearly to see that this was the logical result, but in December, 1863, he urged his friends in New Orleans to recognize the principle of ‘reorganization on the free labor and free suffrage basis.” ‘How would it do,’ he asked of Horace Greeley, ‘to advocate something like this: that the new constitution [of Louisiana] contain a suffrage article;…that all citizens not imprisoned for crime in the country, who desire to exercise the right of suffrage, being twenty-one years of age, present themselves for examination to these commissioners, and on being found able to read and write, and possessed of a competent knowledge of the Constitution of the State and the United States, receive certificates, describing each sufficiently so as to identify him, in virtue of which the citizen receiving it shall be entitled to receive the right of suffrage? Would it not be very honorable for Louisiana and Florida to lead the way in this country to an electoral community with no test except virtue and intelligence?'”16

Biographer Frederick J. Blue wrote: “His supporters there, led by [George] Denison and gubernatorial candidate Benjamin Flanders, another Treasury official, promoted his position on emancipation and suffrage. General Banks’ candidate, Michael Hahn, represented a more cautious view, which was closer to that of the president. It was clear to all that more was at stake than the choice of a governor; a Flanders victory would enhance Chase’s chances for the presidential nomination in 1864. Hahn’s sweeping victory in February 1864 thus represented a personal defeat for Chase. As he explained to Greeley, ‘our truest men are set aside’ because of their advocacy of black suffrage. With a state constitutional convention called for April, Chase continued to urge that the right to vote be determined ‘not by nativity or complexion, but by intelligence, character, and patriotism.”17

Historian Phillip Shaw Paludan wrote: “Privately, Lincoln was encouraging the liberal elements in the state. Since Chase controlled much of the patronage in Louisiana, Lincoln worked with his treasury secretary to push emancipation ideals on treasury appointees. (When conservatives heard of these efforts, Chase, not Lincoln, was scolded.) And on 8 August 1863 the president wrote to General Banks explaining his goal but stressing that he means to that end would determine whether he achieved it.”18

Interior Secretary John Palmer Usher later maintained that the President differed from his Treasury Secretary on the issue of black suffrage: “Mr. Chase, with a great many other Union men, had a different view of that subject, the discussion of which is not now important, further than to state that they held that Congress had the right and power to enact such laws for the government of the people of those States as they might deem expedient for the public safety, including the bestowal of suffrage upon negroes. Mr. Lincoln thought that suffrage, if it ever came to the negroes, should come in other ways. In his Amnesty Proclamation of December 8, 1863, will be found a fair indication of his mind concerning the freed people. He said that any provision by such State ‘which shall recognize and declare their permanent freedom, provide for their education, and which may yet be consistent, as a temporary arrangement, with their present condition as a laboring, landless, and homeless class, will not be objected to by the national executive.” Palmer wrote:

In all his state papers and writings to that date there can found no assertion that he intended to force negro suffrage upon the people of the slave-holding States. Doubtless he contemplated that some time in the future suffrage would be voluntarily yielded to the blacks by the people of those States. From all that could be gathered by those who observed his conduct in those times, it seemed that his hope was that the people in the insurgent States, upon exercising authority under the Constitution and laws of the United States, necessarily recognizing the extinction of slavery, would find it necessary to make suitable provision, not only for the education of the freedmen, as specified in his Amnesty Proclamation, but also for the acquisition of property, and its security in their possession; and, to insure that, would find it necessary and expedient to bestow suffrage upon them in some degree at least.19

Historian LaWanda Cox wrote: “Despite Chase’s presidential ambitions and his self-conscious role as cabinet spokesman for the antislavery vanguard, he and Lincoln worked closely together during 1863 in formulating and implementing administration policy in Louisiana. Most of the patronage appointments for the State were in the Treasury, and they were used to support Lincoln’s policy, if not his prospects for renomination. Chase did not hesitate to urge measures more far-reaching than Lincoln’s, but his letters left their readers in no confusion as to when he spoke for the administration and when he spoke only from his own antislavery convictions. In seeking the destruction of slavery, Chase spoke in Lincoln’s name. He did so in July when he advised members of the Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission that their forthcoming report should distinctly declare that ‘no state which has carried rebellion into a formal act of secession and included in the full enjoyment of the rights of a member of the Union until it has by a fundamental provision or act incorporated in its Constitution recognized and sanctioned the condition established by the Proclamation.'”20

Historian John Hope Franklin wrote: “Another difficulty arose out of the fact that the Treasury contested the right of the War Department to administer Negro affairs. Although the Secretary of War desired the Treasury to control all confiscated property, except that used by the military, officers in the field were of the opinion that they could best handle everything. While the controversy raged during 1863 and 1864, Negroes suffered for wanted of any coordinated supervision.”21 The problem dated back even earlier. Historian LaWanda Cox wrote: “In November 1862, after Secretary [of the Treasury Salmon P.] Chase had read to him a letter from Benjamin Butler, then commanding in Louisiana, which indicated that ‘planters were making arrangements with their negroes to pay them wages,’ Lincoln wrote asking that Butler ‘please write to me to what extent, so far as you know, this is being done.'”22

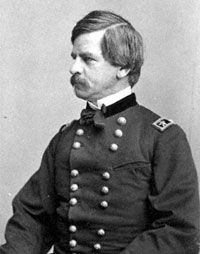

Mr. Lincoln was very sensitive to the rights of black Louisianans who had volunteered early for military service. In early August 1863, President Lincoln wrote General Nathaniel Banks:

Being a poor correspondent is the only apology I offer for not having sooner tendered my thanks for your very successful, and very valuable military operations this year. The final stroke in opening the Mississippi never should, and I think never will, be forgotten.

Recent events in Mexico, I think, render early action in Texas more important than ever, I expect, however, the General-in-Chief, will address you more fully upon this subject.

Governor Boutwell read me to-day that part of your letter to him, which relates to Louisiana affairs. While I very well know what I would be glad for Louisiana to do, it is quite a different thing for me to assume direction of the matter. I would be glad for her to make a new Constitution recognizing the emancipation proclamation, and adopting emancipation in those parts of the state to which the proclamation does not apply. And while she is at it, I think it would not be objectionable for her to adopt some practical system by which the two races could gradually live themselves out of their old relation to each other, and both come out better prepared for the new. Education for young blacks should be included in the plan. After all, the power or element, of ‘contract’ may be sufficient for this probationary period; and, by it’s simplicity, and flexibility, may be the better.

As an anti-slavery man I have a motive to desire emancipation, which pro-slavery men do not have; but even they have strong enough reason to thus place themselves again under the shield of the Union; and to thus perpetually hedge against the recurrence of the scenes through which we are now passing.23

Historians James G. Randall and Richard N. Current, wrote that President Lincoln “did more than send his Negro supplicants away with kind words. When a thousand New Orleans Negroes sent a two-man delegation to Washington (in January, 1864) he responded by assigning James A. McKaye, of the American Freedmen’s Inquiry Commission, to look into their needs and wants. McKaye went to New Orleans, attended a colored mass meeting, and learned that they desired public schools, recognition as human beings, and the abolition of the black codes. Lincoln, apparently impressed by the behavior of the Louisiana Negroes, was willing to grant them a little more than the demanded.”24

Mr. Lincoln initiated action in March 1864. Historian James M. McPherson noted, “Louisiana’s new constitution did not grant the ballot to black men: Race prejudice and the belief that Negroes, though free, were still too ignorant to exercise the rights of citizenship proved too strong.”25 Historian Richard Current wrote: “The new free-state constitution of Louisiana did not enfranchise Louisiana Negroes, though it authorized the legislature to do so – an unlikely prospect in the circumstances. After a visit from a Louisiana black delegation, Lincoln confidentially suggested to Governor Michael Hahn the propriety of giving the vote to at least a few of the ‘colored people.'”26 On March 13, 1864, President Lincoln wrote Governor Hahn: “I congratulate you on having fixed your name in history as the first free-state Governor of Louisiana. Now you are about to have a Convention which, among other things, will probably define the elective franchise. I barely suggest for your private consideration, whether some of the colored people may not be let in – as, for instance, the very intelligent, and especially those who have fought gallantly in our ranks. They would probably help, in some trying time to come, to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom. But this only a suggestion, not the public, but to you alone.”27

Historian LaWanda Cox wrote: “Lincoln’s ‘suggestion’ to Governor Hahn of March 13 is believed to have been precipitated by an interview the previous day with a delegation of free blacks from New Orleans. They brought a petition with a thousand signatures asking to be registered as voters and pointing out that their application to Governor Shepley and General Banks had brought no response. At the meeting, Lincoln expressed that circumstances did not permit the government to confer the right upon them. He gave no indication of the letter he was about to write Hahn, nor any intimation of previous decisions in their favor. The treatment of the delegation again suggests a parallel, this time to Lincoln’s fending off requests for an emancipation proclamation during the period when he had decided to issue one but awaited a propitious moment to do so.”28

Historian Cox wrote: “Even as framed, what Hahn, Banks, and Lincoln had wrought went further than the provisions of the [July 1864] Wade-Davis bill toward establishing equal citizenship. The latter provided only a limited civil equality by directing that laws for the trial and punishment of white persons should extend to all persons during the interim provisional government. No civil rights requirement other than freedom was mandated for inclusion in the state constitutions that would thereafter be controlling. Nor did the Wade-Davis bill breach the suffrage barrier. Indeed, in initiating Reconstruction, Congress would have limited jury duty as well as voting to whites. In comparison, the stillborn free state of Lincoln and Banks represented an advance in the status of free blacks of potentially great significance.”29

Difficult as it was, Mr. Lincoln made more progress in New Orleans than he did in Washington during 1864. Historian LaWanda Cox wrote: “From the perspective of early November 1863, when the momentum for reorganization appeared indefinitely stalled and the prospect of local action to destroy slavery seemed precarious and distant, the Lincoln-Banks initiative had succeeded. Yet the free state they had brought forth was an outcast, shunned or suspect by antislavery men whose cause it was meant to serve, and a precipitant of the mid-year clash between president and Congress over Reconstruction. At the nation’s capital, and throughout the Northeast, Bank’s actions came under immediate and continuing fire. After the September elections, the general left New Orleans for Washington and remained six months in order to help the president develop support for Louisiana’s readmission to the Union. Lincoln and Banks made every effort, yet they failed to obtain recognition from either house of Congress. By the session’s end, Republicans in the Senate would have seated the two Louisianians except for the filibuster of Charles Sumner; but Sumner prevailed. His intransigence was fueled by his commitment to suffrage for blacks.”30

Historian LaWanda Cox wrote: “Another response of Lincoln during the period when Congress was determining the fate of his free state may have been misinterpreted by historians in a way that obscures Lincoln’s determination on the suffrage issue. In December 1864 Lincoln and congressional leaders had apparently agreed to a compromise by which Lincoln, in return for the recognition of Louisiana, would accept the provisions of the Wade-Davis bill for other states substantially unchanged except that the new measure would extend suffrage to all loyal male citizens, that is, to blacks. The first version of the bill was changed within a few days (December 15-December 20) to restore the ‘white’ qualifications except for men in the army and navy.”31 Presidential aide John Hay wrote in his diary in mid-December 1864 about a meeting between President Lincoln, former Postmaster General Montgomery Blair and General Nathaniel Banks:

They immediately began to talk about Ashley[‘]s bill in regard to states in insurrection. The President had been reading it carefully & said that he liked it with the exception of one or two things which he thought rather calculated to conceal a feature which might be objectionable to some. The first was that under the provisions of that bill negroes would be made jurors & voters under the temporary governments. ‘Yes,[“] said Banks, [“}that is to be strick out and the qualification white male citizens of the U.S. is to be restored. What you to would be a fatal objection to the Bill. I would simply throw the Government into the hands of the blacks, as the white people under that arrangement would refuse to vote.”

“The second said the President is the declaration that all persons heretofore held in slavery are declared free. This is explained by some to be not a prohibition of slavery by Congress but a mere assurance of freedom to persons actually then [free] in accordance with the proclamation of Emancipation. In that point of view it is not objectionable though I think it would have been preferable to so express it[.]”

“The President and General Banks spoke very favorably, with these qualifications of Ashley’s bill. Banks is especially anxious that the Bill may pass and receive the approval of the President. He regards it as merely concurring in the Presidents own action in the one important case of Louisiana and recommending an observance of the same policy in other case. He does not regard it, nor does the President, as laying down

Blair talked more than both Lincoln and Banks, and somewhat vehemently attacked the radicals in the house and senate who are at work upon this measure accusing them of interested motives and hostility to Lincoln. The President said “It is much better not to be led from the region of reason into that of hot blood, by imputing to public men motives which they do not avow.”32

Historian LaWanda Cox wrote: ” Although Lincoln undoubtedly shared Bank’s apprehension that neither northern public opinion nor a majority in Congress would sustain unqualified black suffrage, his own view of what was desirable, and perhaps of what was possible, went beyond that of the December 20 revision of the Ashley bill which would enfranchise only black soldiers. And there is good reason to be wary of assuming that Lincoln agreed completely with Banks. The general had lagged behind the president on the suffrage issue a year earlier and may still have approached it with more hesitation than Lincoln. Nonetheless, Banks stood ready to fight for a meaningful extension of suffrage in Louisiana, and expected to win. If in retrospect the hope of success appears unrealistic, it is worth noting that it was also Chase’s assumption as late as April 1865. He wrote urging Lincoln to take ‘the shortest road’ to the admission of Louisiana ‘by causing every proper representation to be made to the Louisiana Legislature.”33

In early January 1865, President Lincoln received a telegram from New York: “A thousand Citizens of New York send you this message. Let no negroes hand drop the bayonet till you have armed it with the ballot.”34 After witnessing the passage of the 13th Amendment by the House of Representatives at the end of January, Frederick Douglass’s son Charles wrote his father “I tell you things are progressing finely…if only they will give us the elective franchise.”35 Ten weeks later, Mr. Lincoln devoted his last public address to issues of reconstruction and black suffrage, saying: “It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that is were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers.”36

We meet this evening, not in sorrow, but in gladness of heart. The evacuation of Petersburg and Richmond, and the surrender of the principal insurgent army, give hope of a righteous and speedy peace whose joyous expression can not be restrained. In the midst of this, however, He, from Whom all blessings flow, must not be forgotten. A call for a national thanksgiving is being prepared, and will be duly promulgated. Nor must those whose harder part gives us the cause of rejoicing, be overlooked. Their honors must not be parcelled out with others. I myself, was near the front, and had the high pleasure of transmitting much of the good news to you; but no part of the honor, for plan or execution, is mine. To Gen. Grant, his skilful officers, and brave men, all belongs. The gallant Navy stood ready, but was not in reach to take active part.

By these recent successes the re-inauguration of the national authority – reconstruction – which has had a large share of thought from the first, is pressed much more closely upon our attention. It is fraught with great difficulty. Unlike the case of a war between independent nations, there is no authorized organ for us to treat with. No one man has authority to give up the rebellion for any other man. We simply must begin with, and mould from, disorganized and discordant elements. Nor is it a small additional embarrassment that we, the loyal people, differ among ourselves as to the mode, manner, and means of reconstruction.

As a general rule, I abstain from reading the reports of attacks upon myself, wishing not to be provoked by that to which I can not properly offer an answer. In spite of this precaution, however, it comes to my knowledge that I am much censured for supposed agency in setting up, and seeking to sustain, the new State Government of Louisiana. In this I have done just so much as, and no more than, the public knows. In the Annual Message of Dec. 1863 and accompanying Proclamation, I presented a plan of rec-construction (as the phrase goes) which, I promised, if adopted by any State, should be acceptable to, and sustained by, the Executive government of the nation. I distinctly stated that this was not only the plan which might possible be acceptable; and I also distinctly protested that the Executive claimed no right to say when, or whether members should be admitted to seats in Congress from such States. This plan was, in advance, submitted to the then Cabinet, and distinctly approved by every member of it. One of them suggested that I should then, and in that connection, apply the Emancipation Proclamation to the theretofore excepted parts of Virginia and Louisiana; that I should drop the suggestion about apprenticeship for free-people, and I should omit the protest against my own power, in regard to the admission of members to Congress; but even he approved every part and parcel of the plan which has since been employed or touched by the action of Louisiana. The new constitution of Louisiana, declaring emancipation for the whole State, practically applies the Proclamation to the part previously accepted. It does not adopt apprenticeship for freed-people; and it is silent, as it could not well be otherwise, about the admission of members to Congress. So that, as it applies to Louisiana, every member of the Cabinet fully approved the plan. The Message went to Congress, and I received many commendations of the plan, written and verbal; and not a single objection to it, from any professed emancipationist, came to my knowledge until after the news reached Washington that the people of Louisiana had begun to move in accordance with it. From July 1862, I had corresponded with different persons, supposed to be interested, seeking a reconstruction of a State government for Louisiana. When the Message of 1863, with the plan before mentioned, reached New-Orleans, Gen. Banks wrote me that he was confident the people, with his military co-operation, would reconstruct, substantially on that plan. I write him, and some of them to try it; they tried it, and the result is known. Such only has been my agency in getting up the Louisiana government. As to sustaining it, my promise is out, as before stated. But, as bad promises are better broken than kept, I shall treat this as a bad promise, and break it, whenever I shall be convinced that keeping it is adverse to the public interest. But I have not yet been so convinced.

I have been shown a letter on this subject, supposed to be an able one, in which the writer expresses regret that my mind has not seemed to be definitely fixed on the question whether the seceded States, so called, are in the Union or out of it. It would perhaps, add astonishment to his regret, were he to learn that since I have found professed Union men endeavoring to make that question, I have purposely forborne any public expression upon it. As appears to me that question has not been, nor yet is, a practically material one, and that any discussion of it, while it thus remains practically immaterial, could have no effect other than the mischievous one of dividing our friends. As yet, whatever it may hereafter become, that question is bad, as the basis of a controversy, and good for nothing at all – a merely pernicious abstraction.

We all agree that the seceded States, so called, are out of their proper practical relation with the Union; and that the sole object of the government, civil and military, in regard to those States, is to again get them into that proper practical relation. I believe it is not only possible, but in fact, easier, to do this, without deciding, or even considering, whether these states have even been out of the Union, that with it. Finding themselves safely at home, it would be utterly immaterial whether they had ever been abroad. Let us all join in doing the acts necessary to restoring the proper practical relations between these states and the Union; and each forever after, innocently indulge his own opinion whether, in doing the acts, he brought the States from without, into the Union, or only gave them proper assistance, they never having been out of it.

The amount of constituency, so to to [sic] speak, on which the new Louisiana government rests, would be more satisfactory to all, if it contained fifty, thirty, or even twenty thousand, instead of only about twelve thousand, as it does. It is also unsatisfactory to some that the elective franchise is not given to the colored man. I would myself prefer that is were now conferred on the very intelligent, and on those who serve our cause as soldiers. Still the question is not whether the Louisiana government, as it stands, is quite all that is desirable. The question is “Will it be wiser to take it as it is, and help to improve it; or to reject, and disperse it?” “Can Louisiana be brought into proper practical relation with the Union sooner by sustaining, or by discarding her new State Government?”

Some twelve thousand voters in the heretofore slave-state of Louisiana have sworn allegiance to the Union, assumed to be the rightful political power of the State, held elections, organized a State government, adopted a free-state constitution, giving the benefit of public schools equally to black and white, and empowering the Legislature to confer the elective franchise upon the colored man. Their Legislature has already voted to ratify the constitutional amendment recently passed by Congress, abolishing slavery throughout the nation. These twelve thousand persons are thus fully committed to the Union, and to perpetual freedom in the state – committed to the very things, and nearly all the things the nation wants – and they ask the nations recognition, and it’s assistance to make good their committal. Now, if we reject, and spurn them, we do our utmost to disorganize and disperse them. We in effect say to the white men “You are worthless, or worse – we will neither help you, nor be helped by you.” To the blacks we say “This cup of liberty which these, your old masters, hold to your lips, we will dash from you, and leave you to the chances of gathering the spilled and scattered contents in some vague and undefined when, where, and how.” If this course, discouraging and paralyzing both white and black, has any tendency to bring Louisiana into proper practical relations with the Union, I have so far, been unable to perceive it. If, on the contrary, we recognize, and sustain the new government of Louisiana the converse of all this is made true. We encourage the hearts, and nerve the arms of the twelve thousand to adhere to their work, and argue for it, and proselyte for it, and fight for it, and feed it, and grow it, and ripen it to a complete success. The colored man too, in seeing all united for him, is inspired with vigilance, and energy, and daring, to the same end. Grant that he desires the elective franchise, will he not attain it sooner by saving the already advanced steps toward it, than by running backward over them? Concede that the new government of Louisiana is only to what it should be as the egg is to the fowl, we shall sooner have the fowl by hatching the egg than by smashing it? Again, if we reject Louisiana, we also reject one vote in favor of the proposed amendment to the national constitution. To meet this proposition, it has been argued that no more than three fourths of those States which have not attempted secession are necessary to validly ratify the amendment. I do not commit myself against this, further than to say that such a ratification would be questionable, and sure to be persistently questioned; while a ratification by three fourths of all the States would be unquestioned and unquestionable.

I repeat the question. “Can Louisiana be brought into proper practical relation with the Union sooner by sustaining or by discarding her new State Government?

What has been said of Louisiana will apply generally to other States. And yet so great peculiarities pertain to each state; and such important and sudden changes occur in the same state; and, withal, so new and unprecedented is the whole case, that no exclusive, and inflexible plan can safely be prescribed as to details and colatterals. Such exclusive, and inflexible plan, would surely become a new entanglement. Important principles may, and must, be inflexible.

In the present “situation” as the phrase goes, it may be my duty to make some new announcement to the people of the South. I am considering, and shall not fail to act, when satisfied that action will be proper. 37

Footnotes

- Susan-Mary Grant and Brian Holden Reid, editor, The American Civil War: Explorations and Reconsiderations, p. 226 (Robert Cook, “The Fight for Black suffrage in the War of the Rebellion”).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 101-102 (Letter to James S. Wadsworth, ca. January, 1864).

- Ward Hill Lamon, Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, p. 242.

- David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee, p. 181.

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 111.

- Marvin R. Cain, Edward Bates of Missouri, p. 223.

- Susan-Mary Grant and Brian Holden Reid, editor, The American Civil War: Explorations and Reconsiderations, p. 224-225 (Robert Cook, “The Fight for Black Suffrage in the War of the Rebellion”).

- Don E. Fehrenbacher, Lincoln in Text and Context, p. 155-156.

- Richard H. Sewell, A House Divided, p. 188.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 93 (John Palmer Usher).

- Richard N. Current, The Political Thought of Abraham Lincoln, p. xxvii.

- Philip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of American Lincoln, p. 254.

- Philip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of American Lincoln, p. 254.

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877, p. 47.

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 110.

- Albert Bushnell Hart, Salmon P. Chase, (Letter from Salmon P. Chase to Horace Greeley).

- Frederick J. Blue, Salmon P. Chase: A Life in Politics, p. 204.

- Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln, p. 247.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 94-95 (John Palmer Usher).

- LaWanda Cox, Lincoln and Black Freedom, p. 55-56.

- John Hope Franklin, From Slavery to Freedom: A History of Negro Americans, p. 274.

- LaWanda Cox, Lincoln and Black Freedom, p. 31.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 365-366 (Letter to Nathaniel Banks, August 5, 1863).

- J. G. Randall and Richard N. Current, “Race Relations in the White House,” Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Leadership of Abraham Lincoln, p. 153-54..

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 110.

- Richard Nelson Current, Speaking of Abraham Lincoln: The Man and His Meaning for Our Times, p. 165.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 243 (Letter to Michael Hahn, March 13, 1864).

- LaWanda Cox, Lincoln and Black Freedom, p. 94-95.

- LaWanda Cox, Lincoln and Black Freedom, p. 103.

- LaWanda Cox, Lincoln and Black Freedom, p. 73-74.

- LaWanda Cox, Lincoln and Black Freedom, p. 119.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 253-254 (December 18, 1864).

- LaWanda Cox, Lincoln and Black Freedom, p. 120-121.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (From J. K. H. Wilcox to Abraham Lincoln, January 5, 1865).

- David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass’ Civil War: Keeping Faith in Jubilee, p. 186 (Letter from Charles R. Douglass to Frederick Douglass, February 9, 1865).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 399-405 (April 11, 1865).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 399-405 (April 11, 1865).