Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “For a variety of reasons the reluctant President could not wait longer; he had to keep at the head of opinion. One reason lay in the fact that the war itself was destroying slavery. Wherever the Union armies penetrated, they abolished servitude, as Lincoln put it, by mere ‘friction and abrasion.’ When Port Royal was captured in South Carolina, thousands of Negroes poured into the military camps; and it was partly for this reason that General Hunter issued his much-applauded order of May, 1862, freeing the slaves of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida wherever they were reached by Northern forces. Lincoln had to revoke that order, but he could not revoke the conditions that elicited it.”1

Historian Nevins wrote that “it was now evident that the war would be long, bloody, and expensive. When McClellan lost his Peninsular campaign, all hope of an early termination of the contest perished. If it were to be long and bloody, emancipation would be justified as a war measure; for it would add to the resources of the North in man power, it would, perhaps, create restlessness among the slaves in certain Southern areas, and, above all, transcending every other consideration, it would put moral purpose into the war. It would, perhaps, create restlessness among the slaves in certain Southern areas, and, above all, transcending every other consideration, it would put moral purpose into the war. It would give millions of Americans a sense that they were fighting a war of human liberation; it would be hailed in Europe as a Messianic edict, closing an unhappy era in the life of the world’s most hopeful nation, and opening a shining new chapter – redeeming the promise of American democracy to the world. Finally, it would meet the more and more exigent demand of Northern opinion, now so steadily crystallizing.”2

Navy Secretary Gideon Welles reported the September 16 Cabinet meeting: “The President was generally advised and consulted, but Seward was the special confidant of General [Winfield] Scott, was more than any one of McClellan, and, in conjunction with Stanton, of Halleck. With wonderful kindness of heart and deference to others, the President, with little self-esteem and unaffected modesty, has permitted this and in a great measure has surrendered to military officers prerogatives intrusted to himself. The mental qualities of Seward are almost the precise opposite of the President. He is obtrusive and never reserved or diffident of his own powers, is assuming and presuming, meddlesome, and uncertain, ready to exercise authority always, never doubting his right until challenged; then he comes timid, uncertain, distrustful, and inventive of schemes to extricate himself, or to change his position. He is not particularly scrupulous in accomplishing an end, nor so mindful of what is due to others as would be expected of one who aims to be always courteous towards equals. The President he treats with a familiarity that sometimes borders on disrespect. The President, though he observes this ostentatious presumption, never receives it otherwise than pleasantly, but treats it as a weakness in one to whom he attributes qualities essential to statesmanship, whose pliability is pleasant, and whose ready shrewdness he finds convenient and acceptable.3

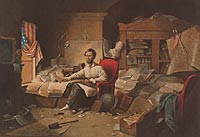

On September 17, 1862, General McClellan confronted Robert E. Lee near the Maryland town of Sharpesville. The Confederate retreat after Battle of Antietam provides Union “victory” needed for Emancipation Proclamation. The President later told artist Francis B. Carpenter: “Finally, came the week of the battle of Antietam. I determined to wait no longer. The news came, I think, on Wednesday, that the advantage as on our side. I was then staying at the Soldiers’ Home, (three miles out of Washington.) Here I finished writing the second draft of the preliminary proclamation; came up on Saturday; called the Cabinet together to hear it, and it was published the following Monday.”4

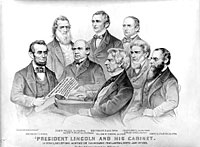

The decisive Cabinet meeting at which President Lincoln announced Emancipation Proclamation was held on September 22. It was this cabinet meeting that Francis Carpenter immortalized in his painting of President Lincoln, Secretary of State Seward, Secretary of War Stanton, Secretary of the Interior Caleb Smith, Attorney General Edward Bates, Postmaster General Montgomery Blair, Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles, and Secretary of the Treasury Chase. Carpenter spent six months at the White House, working on the context and details of that meeting. As usual, the Cabinet had met in the President’s office on the south side of the second Floor of the White House. Attendance at this particular meeting was much better than usual for Mr. Lincoln’s Cabinet. According to John Hay, “The President wrote the Proclamation on Sunday [September 21] morning carefully. He called the Cabinet together on Monday made a little talk to them…and read the momentous document. Mr. Blair and Mr. Bates made objections, otherwise the Cabinet was unanimous. The next day Mr. Blair who had promised to file his objections, sent a note stating that as his objections, sent a note stating that as his objections were only to the time of the act he would not file them, lest they should be subject to misconstruction.”5

Blair apparently did not want to be on the wrong side of history.

Beginning the cabinet meeting about noon on September 22, the President read from a book by humorist Artemus Ward: “In the Faul of 1856, I showed my show in Utky, a trooly grate sitty in the State of New York. 1 Day as I was givin a descripshun of my Beests and Snaiks in my usual flowery stile what was my skorn & Disgust to see a big burly feller walk up to the cage containin my wax figgers of the Lord’s Last Supper, and cease Judas Iscarrot by the feete and drag him out on the grond. He then commenced fur to pound him as hard as he cood.”6 That night, Salmon P. Chase recorded in his diary that after this humorous recitation: “The President then took a graver tone and said:-

‘Gentlemen: I have, as you are aware, thought a great deal about the relation of this war to Slavery; and you all remember that, several weeks ago, I read to you an Order I had prepared on this subject, which, on account of objections made by some of you, was not issued. Ever since then, my mind has been much occupied with this subject, and I have thought all along that the time for action on it might very probably come. I think the time has come now. I wish it were a better time. I wish that we were in a better condition. The action of the army against the rebels had not been quite what I should have best liked. But they have been driven out of Maryland, and Pennsylvania is no longer in danger of invasion. When the rebel army was at Frederick, I determined, as soon as it should be driven out of Maryland, and Pennsylvania is no longer in danger of invasion. When the rebel army was at Frederick, I determined, as soon as it should be driven out of Maryland, to issue a Proclamation of Emancipation such as I thought most likely to be useful. I said nothing to any one; but I made the promise to myself, and (hesitating a little) – to my Maker. The rebel army is now driven out, and I am going to fulfil that promise. I have got you together to hear what I have written down. I do not wish your advice about the main matter – for that I have determined for myself. This I say without intending any thing but respect for any one of you. But I already know the views of each on this question. They have been heretofore expressed, and I have considered them as thoroughly and carefully as I can. What I have written is that which my reflections have determined me to say. If there is anything in the expressions I use, or in any other minor matter, which anyone of you thinks had best be changed, I shall be glad to receive the suggestions. One other observation I will make. I know very well that many others might, in this matter, as in others, do better than I can; and if I were satisfied that the public confidence was more fully possessed by any one of them than by me, and knew of any Constitutional way in which he could be put in my place, he should have it. I would gladly yield it to him. But though I believe that I have not so much of the confidence of the people as I had some time since, I do not know that, all things considered, any other person has more; and, however this may be, there is no way in which I can have any other man put where I am. I am here. I must do the best I can, and bear the responsibility of taking the course which I feel I ought to take.

The President then proceeded to read his Emancipation Proclamation, making remarks on the several parts as he went on, and showing that he had fully considered the whole subject, in all lights under which it had been presented to him.

After he had closed, Gov. Seward said: ‘The general question having been decided, nothing can be said further about that. Would it not, however, make the Proclamation more clear and decided, to leave out all reference to the act being sustained during the incumbency of the present President; and not merely say that the Government ‘recognizes,’ but that it will maintain, the freedom it proclaims?’

I followed, saying: ”What you have said, Mr. President, fully satisfies me that you have given to every proposition which has been made, a kind and candid consideration. And you have now expressed the conclusion to which you have arrived, clearly and distinctly. This it was your right, and under your oath of office your duty, to do. The Proclamation does not, indeed, mark out exactly the course I should myself prefer. But I am ready to take it just as it is written, and to stand by it with all my heart. I think, however, the suggestions of Gov. Seward very judicious, and shall be glad to have them adopted.’

The President then asked us severally our opinions as to modification proposed, saying that he did not care much about the phrases he had used. Everyone favored the modification and it was adopted. Gov. Seward then proposed that in the passage relating to colonization, some language should be introduced to show that the colonization proposed was to be only with the consent of the colonists, and the consent of the States in which colonies might be attempted. This, too, was agreed to; and no other modification was proposed. Mr. Blair then said that the question having been decided, he would make no objection to issuing the Proclamation; but he would ask to have his paper, presented some days since, against the policy, filed with the Proclamation. The President consented to his readily. And then Mr. Blair went on to say that he was afraid of the influence of the Proclamation on the Border States and the Army, and stated at some length the grounds of his apprehensions. He disclaimed most expressly, however, all objection to Emancipation per se, saying he had always been personally in favor it – always ready for immediate Emancipation in the midst of Slave States, rather than submit to the perpetuation of the system.7

There was apparent unanimity on the goal of the proclamation, but Postmaster General Montgomery Blair raised questions about the impact on the loyalty of residents of the Border States of Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, and Missouri. This was a sensitive issue for Mr. Lincoln, who was always concerned about the loyalty of this section of the Union. Although Blair urged that action be postponed until after the fall congressional elections, President Lincoln later maintained that “No member of the Cabinet ever dissented from the policy, in any conversation with me.”8 Blair told Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles years later that “it was due to Lincoln himself that I hesitated. I had urged him previously to make the proclamation and a letter of mine will be found among his papers arguing the point, he had scarcely a week before ridiculed the idea of such a proclamation…and I had to support him against Chase and therefore [was] taken aback by his somersault at first, and so hesitated, but after sleeping on it I came to my former position.”9 Welles himself recorded his version of that Cabinet meeting at which the final decision on the proclamation was made:

The subject was the Proclamation for emancipating the slaves after a certain date, in States that shall then be in rebellion. For several weeks the subject has been suspended, but the President says never lost sight of. When it was submitted, and now in taking up the Proclamation, the President stated the question was finally decided, the act and the consequences were his, but that he felt it due to us to make us acquainted with the fact and to invite criticism on the paper which he had prepared. There were, he had found, not unexpectedly, some difference in the Cabinet, but he had, after ascertaining in his own way the views of each and all, individually and collectively, formed his own conclusions and made his own decisions. In the course of the discussion on this paper, which was long, earnest, and on the general principle involved, harmonious, he remarked that he had made a vow, a covenant, that if God gave up the victory in the approaching battle, he would consider it an indication of Divine will, and that it was his duty to move forward in the cause of emancipation. It might be thought strange, he said, that he had in this way submitted the disposal of matters when the way was not clear to his mind what he should do. God had decided this question in favor of the slaves. He was satisfied it was right, was confirmed and strengthened in his action by the vow and the results. His mind was fixed, his decision made, but he wished his paper announcing his course as correct in terms as it could be made without any change in his determination. He read the comment. One or two unimportant amendments suggested by Seward were approved. It was then handed to the Secretary of State to publish to-morrow. After this, [Postmaster General Montgomery] Blair remarked that he considered it proper to say he did not concur in the expediency of the measure at this time, though he approved of the principle, and should therefore wish to file his objections. He stated at some length his views, which [were] substantially that we ought not to put in greater jeopardy the patriotic element in the Border States, that the results of the Proclamation would be to carry over those States en masse to the Secessionists as soon as it was read, and that there was also a class of partisans in the Free States endeavoring to revive old parties, who would have a club put into their hands of which they would avail themselves to beat the Administration.

The President said he had considered the danger to be apprehended from the first objection, which was undoubtedly serious, but the objection was certainly as great not to act; as regarded the last, it had not much weight with him.

The question of power, authority, in the Government to set free the slaves was not much discussed at this meeting, but had been canvassed by the President in a private conversation with the members individually. Some thought legislation advisable before the step was taken, but Congress was clothed with no authority on this subject, nor is the Executive, except under the war power,-military necessity, martial law, when there can be no legislation. This was the view which I took when the President first presented the subject to Seward and myself last summer as we were returning from the funeral of Stanton’s child,-a ride of two or three miles from beyond Georgetown. Seward was at that time not at all communicative, and, I think, not willing to advise, thought he did not dissent from, the movement. It is momentous both in its immediate and remote resolute, and an exercise of extraordinary power which cannot be justified on mere humanitarian principles, and would never have been attempted but to preserve the national existence. The slaves must be with us or against us in the War. Let us have them. These were my convictions and this the drift of the discussion.

The effect which the Proclamation will have on the public mind is a matter of some uncertainty. In some respects it would, I think, have been better to have issued it when formerly first considered.

There is an impression that Seward has opposed, and is opposed to, the measure. I have not been without that impression myself, chiefly from his hesitation to commit himself, and perhaps because action was suspended on his suggestion.

But in the final discussion he has as cordially supported the measure as Chase.10

Treasury official Maunsell B. Field recalled: “Mr. Seward told me the story of the Emancipation Proclamation, and, as he related it, it was strikingly illustrative of this characteristic of Mr. Lincoln. Months before it was issued, it was the subject of constant discussion at the meetings of the Cabinet. Day after day the most earnest and acrimonious debates took place in relation to the propriety or impropriety of the President issuing such a proclamation. Although an attentive listener to these discussions of his Secretaries, Mr. Lincoln did not take an active part in them. So much was this the case that several, at least, of his advisers were very uncertain as to what his ultimate determination upon the subject would be. So bitter did the controversy grow, that it resulted, after a time, not only in a breach of personal, and to some extent even official relations between certain of the Cabinet officers, but eventually even in a prolonged discontinuance of Cabinet meetings. During the interregnum matters which had been usually discussed and disposed of at such meetings had to be settled by inter-departmental correspondence. One of the other Secretaries, with the obvious purpose of annoying – I use a mild word – Mr. Chase, addressed several very important official communications directly to me, ignoring the head of Department. This condition of things lasted until one day Mr. Seward received an autographic letter from the President requesting him to attend, without fail, a meeting of the Cabinet which he proposed to hold on the morrow. All the other Secretaries received similar letters, and not one of them knew or entertained any confident conjecture about the particular purpose for which they were called together. At the appointed time Mr. Lincoln waited until they were all assembled, having been unusually reticent to the first comers. He then addressed them somewhat as follows: ‘Gentlemen, I have asked you to come here that I have the opportunity of reading to you a proclamation which I am about to issue. Before proceeding to read it, however, I desire to say that not only do I not invite any discussion about the propriety or impropriety of its issue, but that I am unwilling to listen to any. My mind is made up. On the contrary, as to matters of form, I wish you all to make any suggestions that may occur to you.’ He then drew from his pocket a manuscript, and to the amazement of some, if not of all, there assembled, proceeded to read the Emancipation Proclamation. When he had finished, for a while nobody spoke. Mr. Seward was the first to break the silence, and to recommend a verbal alteration. Mr. Lincoln adopted it without a word of objection. Other gentlemen suggested further changes. Mr. Lincoln accepted them all without discussion. When nobody had any more suggestions to make, the meeting broke up, and the Ministers soon dispersed. The next day the emancipation from slavery of four millions of human beings in the United States was published to the world. Mr. Lincoln had waited until the people were ripe for it; and what he had at first looked upon as inopportune, he had at least regarded as expedient and necessary.”11

According to Francis B. Carpenter at the final meeting of September 22th, “another interesting incident occurred in connection with Secretary Seward. The President had written the important part of the proclamation in these words:-

“That, on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever FREE; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.” “When I finished reading this paragraph,” resumed Mr. Lincoln, “Mr. Seward stopped me, and said, “I think, Mr. President, that you should insert after the word “recognize,” in that sentence, the words, “and maintain.”‘ I replied that I had already fully considered the import of that expression in this connection, but I had not introduced it, because it was not my way to promise what I was not entirely sure that I could perform, and I was not prepared to say that I thought we were exactly able to ‘maintain’ this.”

‘But,” said he, “Seward insisted that we ought to take this ground; and the words finally went in!”

“It is a somewhat remarkable fact,” he subsequently remarked, “that there were just one hundred days between the dates of the two proclamations issued upon the 22d of September and the 1st of January. I had not made the calculation at the time.”

Having concluded this interesting statement, the President then proceeded to show me the various positions occupied by himself and the different members of the Cabinet, on the occasion of the first meeting. “As nearly as I remember,” said he, “I sat near the head of the table; the Secretary of the Treasury and the Secretary of War were here, at my right hand; the others were grouped at the left.”12

Another New York politician later suggested to painter Carpenter that politician Seward was arranging the picture for history. New York businessman Hiram Barney wrote Gideon Welles a decade later: “The engraving, taken, I think from Carpenter’s painting of the Proclamation of Emancipation, represents Mr. Seward, with pen in hand, as if he had written that paper and had then submitted it to Mr. Lincoln and the cabinet. It is very probable that Mr. Seward chose for himself this attitude in the group, so as to produce the impression that he was the author of that great measure and of the instrument by which it was declared to the world.”13 Other Cabinet members did not appreciate the prominent pictorial position which Seward had appropriated for himself in history.

In 1877, Barney once again wrote Welles: “You were right in thinking that my interview after we left you [on day in the summer of 1862 ] was on the subject of the proclamation which was drafted in his own handwriting and in his pocket when we were together. When we reached what he thought was a place secure against interruption he read and showed it to me, and then, at my request, read it a second time for my suggestions. I made one which he adopted and advised him about the time and circumstances in which it should be issued. But we were interrupted three times by Mr. Seward, who came through closed doors and two empty rooms to find us and tried to hush up our conference, though he could have no more than a suspicion, if he had that, of the subject of our conversation. Mr. Lincoln requested me not to talk about it, ‘for,’ said he, ‘no human being has seen this or knows anything about it.’ I think he wanted a witness to the fact that it was all his own work. Carpenter’s picture groups the figures so that it would appear that Seward has just finished his draft and Mr. Lincoln was reading it for the first time. But the fact is Seward was not very well pleased with the measure.”14

“Now that Lincoln had proclaimed emancipation, antislavery Republicans were eager to claim credit for having helped push him to his decision, or to attribute credit to the stoutly antislavery Cabinet member Salmon P. Chase, even while they might carp that Lincoln had not gone far enough because he left slavery untouched in the loyal and reconquered areas,” wrote historian Russell F. Weigley.15 Chase had looked for political advantage on the emancipation issue. Historian Donnal V. Smith wrote: “Chase did not yet give up hope of destroying such political advantage as might result to the administration, for the very next day he again wrote to Butler to tell him that he ‘must anticipate a little the operation of the Proclamation in New Orleans and Louisiana. The law frees all slaves of rebels in any city occupied by our troops and previously occupied by the rebels. This is the condition in New Orleans. Is it not clear then, that the presumption is in favor of every man, only to be set aside in case of some clear proof of continuous loyalty?’ It was Chase’s last hope – all that was left was criticism and protest. ‘You have before this seen the Proclamation of the President,’ he wrote to S.G. Arnold, ‘I hope a new vigor and activity in military affairs may follow. I can only hope, however, for I have no voice in the conduct of the war and am not responsible for it, except in the provision of the necessary funds…’ To another, Chase implied that he had proposed more radical measures with regard to the negro long ago but ‘as the President did not concur in this judgment I was willing and indeed very glad to accept the Proclamation as the next best mode of dealing with the subject.'”16

Presidential aides John G. Nicolay and John Hay wrote: “A careful reading and analysis of the document shows it to have contained four leading propositions: (1) A renewal of the plan of compensated abolishment. (2) A continuance of the effort at voluntary colonization. (3) The announcement of peremptory military emancipation of all slaves in States in rebellion at the expiration of the warning notice. (4) A promise to recommend ultimate compensation to loyal owners.”17

Historian Kenneth M. Stamp wrote: “The fact that Lincoln had decided a month before his reply to Greeley to issue an Emancipation Proclamation did not mean that he was secretly pursuing one policy and publicly another. In his Preliminary Proclamation of September 22, 1862, he announced that ‘hereafter, as heretofore,’ the war would be prosecuted to preserve the Union, and that he would continue to press for voluntary, gradual, compensated emancipation and colonization.”18 But that the Lincoln Administration had a new policy direction, few could deny.

Footnotes

- Allan Nevins, The Statesmanship of the Civil War, p. 130.

- Allan Nevins, The Statesmanship of the Civil War, p. 130-131.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 135 (September 16, 1862).

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, p. 22-23.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 40 (September 24, 1862).

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 289.

- David H. Donald, editor, Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet: The Civil War Diaries of Salmon P. Chase, p. 149-152.

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, p. 88.

- William Ernest Smith, The Francis Preston Blair Family in Politics, Volume II, p. 186.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume I, p. 142-144 (September 13, 1862).

- Maunsell B. Field, Personal Recollections: Memories of Many Men and of Some Women, p. 265-266.

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, p. 23-24.

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 364 (Letter from Hiram Barney to Gideon Welles, December 4, 1873).

- Burton J. Hendrick, Lincoln’s War Cabinet, p. 364 (Letter from Hiram Barney to Gideon Welles, September 27, 1877).

- Russell F. Weigley, A Great Civil War: A Military and Political History, 1861-1865, p. 176.

- Donnal V. Smith, Salmon P. Chase and the Election of 1860, Ohio Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, July 1930, p. 555-556.

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VI, p. 169-170.

- Gabor S. Boritt, editor, Lincoln the War President, p. 138 (Kenneth M. Stamp, “The United States and National Self-determination”).

Visit

Hiram Barney (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Edward Bates (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Benjamin Butler (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Montgomery Blair (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Francis B. Carpenter (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Salmon P. Chase (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

John Hay (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

John Hay (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

John Nicolay (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

John Nicolay (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

William H. Seward (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Caleb Smith (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Edwin M. Stanton (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Edwin M. Stanton (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Gideon Welles (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)