“Here was the document that offered Freedom Now for the enslaved Negro. That was the first step, taken in the midst of war, ‘upon military necessity’ more than for high moral purposes. Nevertheless, its effects were electrifying in the United States and abroad. Certainly more than any other document or decision in American history, it was recognized by whites and Negroes themselves as the symbol of freedom.” wrote Lincoln chronicler Herbert Mitgang.1 Historian Allan Nevins wrote of the Emancipation Proclamation: “All students of history have agreed that the step was taken at precisely the right moment, and in precisely the right way. It was not taken too soon, or until all decent alternatives had been thoroughly explored. It was assuredly not taken a moment too late.”2 Lincoln biographer Isaac N. Arnold, who was a friend of President Lincoln, wrote: “This edict was the pivotal act of his administration, and may be justly regarded as the great event of the century.”3

Historian Allen C. Guelzo wrote: “If anything we underestimate the political courage it took for Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation and then stand behind it. Six weeks after he gave his hundred-days’ warning, the midterm congressional elections dumped 45 Republicans from their seats in the House of Representatives. The Union army smoldered with rumors of mutiny and coup. Two state legislatures – Illinois and Indiana – were so violent in their condemnation of the Proclamation that they had to be closed down by their governors. And in July 1863, New York City erupted in a riot over the draft that quickly turned into a bloody anti-emancipation carnival.”4

Not everyone recognized Lincoln’s courage. In a speech on the House floor, Kentucky Congressman Robert Mallory alleged that President Lincoln had caved into the demands of Republican Radicals such as Pennsylvania’s Thaddeus Stevens: “Soon after the War broke out, the gentleman from Pennsylvania and his great allies Horace Greeley and Wendell Phillips, and all his little allies in the House, began their pressure on the President and the Republican Party. In vain the President from time to time besought his friends, and those who had not been his friends, to relieve him from this pressure.” Mallory, who was one of the Border State representatives who had rejected Mr. Lincoln’s plea for compensated emancipation, said: “The gentleman from Pennsylvania and his allies persevered. They demanded of the President his proclamation of emancipation. He refused. Again they demanded it; he refused again, but more faintly and exhibited himself in his letter to his ‘dear friend Greeley’ in the most pitiable and humiliating attitude in which an American President was ever exhibited to the American people – But the gentleman from Pennsylvania still pressed him and educated him and the Republicans.”5

Historian T. Harry Williams wrote: “The radical press thought the general tone of the proclamation was adequate, but Greeley and other editors blasted Lincoln savagely for excepting from its operation the areas under Union control. They called upon the president to give further proof of his devotion to the cause of freedom. A conservative journal noted: ‘The proclamation of the President is not acceptable to the Radicals. They argue that it is not universal, and is therefore not up to the mark. They think it will not be effectual unless the President places men in the army who are in favor of it.’ Lincoln had waited too long to espouse emancipation, said a Democratic observer, and now the radicals did not trust his sincerity: ‘…[He] has made no friends among them, for the reason that he has not done everything in their particular way, and at their designated moment.'”6

The Illinois Journal found much to praise in the work of its long-time collaborator in Washington: “This great man, whom it is not extravagant to say is God-like in his moral attributes, child-like in the simplicity and purity of his character, and yet manly and self-relying in his high and patriotic purpose – this man who takes no step backward – let him consummate the grandest achievement ever allotted to man, the destruction of American slavery.”7

Historian T. Harry Williams wrote: “If the proclamation did not raise cries of delight from the Jacobins, it fell stillborn among the conservative Republicans. Harper’s and the New York Times indorsed it, but in general it met a hostile reception in conservative circles. Lincoln’s friend [Orville H.] Browning criticized it savagely. The most dangerous attack came from Thurlow Weed, Seward’s manager and the boss of the silk-hat Republican machine in New York. In his newspaper organ Weed denounced the edict as turning the war into an abolition crusade, and flayed the ‘blind and frantic course’ of the radicals, ‘by whom the administration is beleaguered, importuned, and persecuted.'”8

Historian Benjamin Thomas wrote: “The public reaction was mixed. Many persons experience a bewilderment of joy, but sullen notes intruded. As Lincoln had anticipated, abolitionist extremists expressed dissatisfaction at a halfway measure. Some persons in the border states predicted a social cataclysm. Proslavery Northern Democrats saw Lincoln’s perfidy unmasked; after wheedling them into supporting a war for the Union he had turned for the Union, he had turned it against slavery.”9 According to T. Harry Williams, “To the Democrats the proclamation was the final example of Lincoln’s perfidy in soliciting Democratic support for a war to restore the Union and at the same time capitulating to the radicals on every issue. The mask was now off,

they shouted, and they would have no more of Mr. Lincoln and his glib talk about an all-parties policy. Let Wade and Chandler run his war for him! An inauspicious portent for the president was the announced opposition of a powerful prelate of the Catholic church. The newspaper organ of Bishop [John] Hughes of New York condemned the proclamation and the congressional radicals who had forced the issue.”10

Describing the army reaction to the Emancipation Proclamation in early January 1863, historian T. Harry Williams wrote that many letters to the editor were written by “officers who claimed to have been Republicans but who were now bolting the part because they could not stomach the emancipation proclamation and the mismanagement of the war. Among the private soldiers the new emancipation policy excited disgust and opposition. Henry Raymond picked up a story that the New Jersey regiments in Burnside’s army had declared that they would not fight in an antislavery war because their state had just elected a Peace Democrat to the Senate, thereby demonstrating its opposition to the administration program. [Joseph] Hooker later furnished the [War Oversight] committee with an accurate picture of the army’s dangerous state of mind: ‘At that time perhaps a majority of the officers, especially those high in rank, were hostile to the policy of the government in the conduct of the war. The emancipation proclamation had been published a short time before, and a large element of the army had taken sides antagonistic to it, declaring that they would never have embarked in the war had they anticipated this action of the government.'”11

Historian Willard L. King wrote that President Lincoln even had trouble in his home state: “In January 1863, the legislature of Illinois, under Democratic domination, proposed resolutions demanding an immediate cessation of the war unless the Emancipation Proclamation were withdrawn. Test votes showed that such resolutions would be passed. [David] Davis went at once to the White House and told Lincoln that, to save the country, he must change the policy regarding slavery – the Emancipation Proclamation had made suppression of the Rebellion impossible. The Judge also told the President that he must reconstruct his cabinet to eliminate Chase and Blair. Lincoln replied that his policy regarding slavery was fixed – that he meant to adhere to it, and that whether he changed his cabinet must be determined by future events.”12

Historian T. Harry Williams wrote that “while the radicals muttered and conservatives fell away, one strange recruit appeared in the administration ranks. In a speech at Music Hall in Boston, Wendell Phillips announced that at last he could rejoice under the banner of the United States. A disgusted editor snorted: ‘The proclamation may lose us Kentucky, but then it has given us Mr. Phillips. He will doubtless take the field with a formidable army of twenty thousand adjectives.'”13 William K. Klingaman wrote in Abraham Lincoln and the Road to Emancipation, 1861-1865: “Measured against Lincoln’s wartime expectations, the Emancipation Proclamation proved a resounding success. It encouraged slaves in the Confederate states to flee their masters, or at least slow their work and grow insubordinate. The heightened possibility of slave insurrection distracted Confederate officials and lowered morale in the rebel armies.”14

Meanwhile President Lincoln wrote a letter of thanks to the Working-men of Manchester who had passed a resolution:

As citizens of Manchester, assembled at the Free-Trade Hall, we beg to express our fraternal sentiments toward you and your country. Wee rejoice in your greatness as an outgrowth of England, whose blood and language you share, whose orderly and legal freedom you have applied to new circumstances, over a region immeasurably greater than our own. We honor your Free States, as a singularly happy abode for the working millions where industry is honored.

One thing alone has, in the past, lessened our sympathy with your country and our confidence in it; we mean the ascendancy of politicians who not merely maintained Negro slavery, but desired to extend and root it more firmly.

Since we have discerned, however, that the victory of the free north, in the war which has so sorely distressed us as well as afflicted you, will strike off the fetters of the slave, you have attracted our warm and earnest sympathy. We joyfully honor you, as the President, and the Congress with you, for many decisive steps toward practically exemplifying your belief in the words of your great founders: ‘All men are created free and equal.’ You have procured the liberation of the slaves in the district around Washington, and thereby made the centre of your Federation visibly free. You have enforced the laws against the slave-trade, and kept up your fleet against it, even while every ship was wanted for service in your terrible war. You have nobly decided to receive ambassadors from the Negro republics of Hayti and Liberia, thus forever renouncing that unworthy prejudice which refuses the rights of humanity to men and women on account of their color. In order more effectually to stp the slave-trade, you have made with our Queen a treaty, which your Senate has ratified, for the right of mutual search. Your Congress has decreed freedom as the law forever in the vast unoccupied or half unsettled Territories which are directly subject to its legislative power. It has offered pecuniary aid to all States which will enact emancipation locally, and has forbidden your Generals to restore fugitive slaves who seek their protection. You had entreated the slave-masters to accept these moderate offers; and after long and patient waiting, you, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army, have appointed to-morrow, the first of January, 1863, as the day of unconditional freedom for the slaves of the rebel states.

Heartily do we congratulate you and your country on this humane and righteous course. We assume that you cannot now stop short of complete uprooting of slavery. It would not become us to dictate any details, but there are broad principles of humanity which must guide you. If complete emancipation in some States be deferred, though only to a predetermined day, still in the interval, human beings should not be counted chattels. Women must have the rights of chastity and maternity, men the rights of husbands, masters the liberty of manumission. Justice demands for the black, no less than for the white, the protection of law – that his voice be heard in your courts. Nor must any such abomination be tolerated as slave-breeding States, and a slave market – if you are to earn the high reward of all your sacrifices, in the approval of the universal brotherhood and of the Divine Father. It is for your free country to decide whether any thing but immediate, and total emancipation can secure the most indispensable rights of humanity against the inveterate wickedness of local laws and local executives.

We implore you, for your own honor and welfare, not to faint in your providential mission. While your enthusiasm is aflame, and the tide of events runs high, let the work be finished effectually. Leave no root of bitterness to spring up and work fresh misery to your children. It is a mighty task, indeed, to reorganize the industry not only of four millions of the colored race, but of five millions of whites. Nevertheless, the vast progress you have made in the short space of twenty months fills us with hope that every stain on your freedom will shortly be removed, and that the erasure of that foul blot upon civilization and Christianity – chattel slavery – during your Presidency will cause the name of Abraham Lincoln to be honored and revered by posterity. We are certain that such a glorious consummation will cement Great Britain to the United States in close and enduring regards. Our interests, moreover, are identified with yours. We are truly one people, though locally separate. And if you have any ill-wishers here, be assured they are chiefly powerless to stir up quarrels between us, from the very day in which your country becomes, undeniably and without exception, the home of the free.

Accept our high admiration of your firmness in upholding the proclamation of freedom.”15

President Lincoln took the opinions of British working people and their sufferings. His reply reflected his appreciation:

I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of the address and resolutions which you sent to me on the eve of the new year.

When I came, on the fourth day of March, 1861, through a free and constitutional election, to preside in the government of the United States, the country was found at the verge of civil war. Whatever might have been the cause, or whosoever the fault, one duty paramount to all others was before me, namely, to maintain and preserve at once the Constitution and the integrity of the federal republic. A conscientious purpose to perform this duty is a key to all the measures of administration which have been, and to all which will hereafter be pursued. Under our form of government, and my official oath, I could not depart from this purpose if I would. It is not always in the power of governments to enlarge or restrict the scope of moral results which follow the policies that they may deem it necessary for the public safety, from time to time, to adopt.

I have understood well that duty of self-preservation rests solely with the American people. But I have at the same time been aware that favor or disfavor of foreign nations might have a material influence in enlarging and prolonging the struggle with disloyal men in which the country is engaged. A fair examination of history has seemed to authorize a belief that the past action and influences of the United States were generally regarded as having been beneficent towards mankind. I have therefore reckoned upon the forbearance of nations. Circumstances, to some of which you kindly allude, induced me especially to expect that if justice and good faith should be practiced by the United States, they would encounter no hostile influence on the part of Great Britain. It is now a pleasant duty to acknowledge the demonstration you have given of your desire that a spirit of peace and amity towards this country may prevail in the councils of your Queen, who is respected and esteemed in your own country only more than she is by the kindred nation which has its home on this side of the Atlantic.

I know and deeply deplore the sufferings which the workingmen at Manchester and in all Europe are called to endure in this crisis. It has been often and studiously represented that the attempt to overthrow this government, which was built upon the foundation of human rights, and to substitute for it one which should rest exclusively on the basis of human slavery, was likely to obtain the favor of Europe. Through the actions of our disloyal citizens the workingmen of Europe have been subjected to a severe trial, for the purpose of forcing their sanction to that attempt. Under these circumstances, I cannot but regard your decisive utterance upon the question as an instance of sublime Christian heroism which has not been surpassed in any age or in any country. It is, indeed, an energetic and reinspiring assurance of the inherent power of truth and of ultimate and universal triumph of justice, humanity, and freedom. I do not doubt that the sentiments you have expressed will be sustained by your great nation, and, on the other hand, I have no hesitation in assuring you that they will excite admiration, esteem, and the most reciprocal feelings of friendship among the American people. I hail this interchange of sentiment, therefore, as an augury that, whatever else may happen, whatever misfortune may befall your country or my own, the peace and friendship which now exist between the two nations will be, as it shall be my desire to make them, perpetual16

The British elite were less easily persuaded. The London Times, however, was not impressed by the President’s Proclamation, which it thought reflect his impotence rather than his power: “It must also be remembered that this act of the PRESIDENT, if it purposed to strike off the fetters of one race, is a flagrant attack on the liberties of another. The attempt to free the blacks is a flagrant attack on the liberties of the whites. Nothing can be more unconstitutional, more illegal, more entirely subversive of the compact on which the American Confederacy rests, that the claim set up by the PRESIDENT to interfere with the laws of individual States by his Proclamation, unless, indeed, it be the attempt of Congress to dismember the ancient State of Virginia, and create a new State upon its ruins. It is preposterous to say that war gives these powers; they are the purest usurpation, and, though now used against the enemies of the Union, are full of evil presage for the liberties of the States that still adhere to it. It is true that the President advises the negroes to abstain from all violence except in self-confidence, and to labour for reasonable wages. But the President well knows that not a slaveholder in the South will obey his Proclamation, that it can only be enforced by violence, and that if the negroes obtain freedom it will be by the utter destruction of their masters. In such a state of society to speak of wages – that is, of a contract between master and servant – is a cruel mockery. In the South the negro can only exist apart from his master by a return to the savage state – a state in which, amid blood and anarchy and desolation, he may frequently regret the fetters he has broken, and even the master whom he has destroyed. He cannot hope for a better situation than that of his race in the North – a situation of degradation, humiliation, and destitution which leaves the slave very little to envy. Mr. LINCOLN bases his act on military necessity, and invokes the considerate judgment of mankind and the judgment of ALMIGHTY GOD. He has characterized his own act; mankind will be slow to believe that an act avowedly the result of military considerations has been dictated by a sincere desire for the benefit of those who, under the semblance of emancipation, are thus marked out for destruction, and HE who made man in His own image can scarcely, we may presume to think, look with approbation on a measure which, under the pretence of emancipation, intends to reduce the South to the frightful condition of Santo Domingo.”17

Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “Much has been written about the limitations of the great proclamation. It did not free the slaves in those areas which had never ‘rebelled,’ nor in districts where the ‘rebellion’ had been suppressed. In sober fact, it applied to the slaves on in areas where the national government as yet had no authority. Yet it was nevertheless an immortal blow for human freedom. It not only changed the aims of the war, but it raised them to a higher level. Infusing a new moral meaning into the conflict, it deepened that element of passion and inspiration which vibrated in so many of Lincoln’s utterances. It rallied the liberal thought of Britain and the globe to the Union side. Month by month, year by year, it had a widening influence. ‘Great,’ wrote [Ralph Waldo] Emerson, ‘is the virtue of this Proclamation. It works when men are sleeping, when the army goes into winter quarters, when generals are treacherous or imbecile.’ In its way, it is working still.” 18

“The Emancipation alone may not have been enough to embolden these black men to seek the rights of other citizens, but its very existence doubtless helped to steel their resolve to do so. It gave them hope that full inclusion in American society was a dream about to be realized,” wrote historian Edna Greene Medford. “African-Americans expected much from Lincoln’s proclamation. In addition to it enabling them to acquire freedom and equality, they saw it as the path by which a people debased by slavery would be reconstructed. Black Civil War correspondent Thomas Morris Chester believed that in breaking the shackles of the enslaved, the Emancipation Proclamation

…protects the sanctity of the marriage relationship and lays the foundation for domestic purity…releases from licentious restraint our cruelly treated women and defends them in the maiden chastity which instincts suggest…justifies the natural right of the mother over the disposition of her daughters, and gives to the father the only claim which Almighty God intended should be exercised by man over his son…puts an end to the blasphemy and the perversion of the scriptures, and inaugurates those higher and holier influences which will prosper all the people and bless the land from the Atlantic to the Pacific…ends the days of oppression, cruelty and outrage, founded on complexion, and introduces an era of emancipation, humanity and virtue, founded upon the principles of unerring justice.19

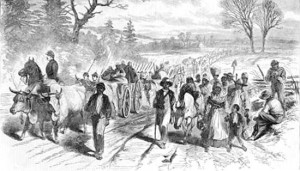

According to historian James M. McPherson: “Some slaves, especially those far from the scene of fighting, had little understanding of what was going on. They remained quietly at home and continued to hoe cotton or tobacco. But most slaves were aware of the issues of the war and their meaning for the future of African-Americans. Thousands of slaves in areas near the Northern army camps left their plantations and went over to the Yankees the first chance they had. This action by slaves ‘voting with their feet’ for freedom forced the Union army to define these escaped slaves as ‘contrabands.’ Thus, the slaves themselves took the first step to achieve their freedom. More than half a million of the 3,500,000 slaves in the Confederacy came into Union lines and gained freedom during the war.”20

New York industrialist Peter Cooper wrote in September 1863 that he had learned from the St. Louis provost marshal “that the Proclamation of Freedom has done more to weaken the rebellion…than any other measure that could have been adopted. On his late visit to my house he informed me that he had brought on a large number of rebel officers and men to be exchanged at Fortress Monroe. During their passage he took the opportunity to ask the officers in a body what effect the President’s Proclamation of Freedom had produced in the South. Their reply was…that ‘it had played hell with them. Mr. Dean then asked them how that could be possible, since the negroes cannot read. To which one of them replied that one of his negroes had told him of the proclamation five days before he heard it in any other way. Others said their negroes gave them their first information of the proclamation.”21

Historian Edna Greene Medford wrote: “In those areas of the South occupied by Union troops, black men and women celebrated ‘the day of jubilee’ in much the same way as did African-Americans in the North. Although not included in the emancipating provisions of the proclamation, enslaved men and women in cities such as Norfolk and New Orleans – where the Union presence had already weakened slavery’s hold – welcomed the president’s pronouncement as a sure sign of the inevitability of their own freedom. In Norfolk thousands watched and cheered as Union troops and representatives from the black community paraded down the main streets in celebration of Lincoln’s decree. Even in the border states, enslaved people recognized the significance the document held for their future liberation. In Kentucky, for instance, news of the preliminary proclamation had convinced African-Americans that their freedom was imminent, despite efforts on the part of local slaveholders to dispel the belief.”22 Historian Allan Nevins wrote:

“But the proclamation had three immediate, positive, and visible effects. First, every forward step the Union armies took after January 1, 1863, now became a liberating step. Every county in Mississippi, Alabama, Virginia and the Carolinas that passed under military control was thenceforth legally free-soil country, the army bound to ‘recognize and maintain’ emancipation.

“In the second place, the percolating news of the proclamation encouraged slaves to escape, bringing them first in trickles and then rivulets within army lines. How did it percolate? By grapevine telegraph, by the overheard discussions of masters, by glimpses of newspapers, by a new tension in the air. The idea that nearly all slaves wishes to cling to their masters, a staple of Southern white folklore, did not fit the facts, for whenever escape became feasible, most of them were ready to embrace the opportunity. Edmund Ruffin, prominent among those who defended slavery as a positive good, must have been shocked when after McClellan’s invasion nearly the whole work force decamped from his ‘Marbourne’ plantation in Princess Anne County. A few days later he wrote in his diary: ‘The fleeing of slaves from this neighborhood, which seemed to have ceased, has begun again. Mr. J.B. Bland lost 17 more a few nights ago, making his whole loss 27 – though 5 were recaptured.'”23

Nevins added that “in the third place, the proclamation irrevocably committed the United States, before the gaze of the whole world, to the early eradication of slavery from those wide regions where it was most deeply rooted; after which, all men knew, it could never survive on the borders. There could be no turning back. The government had dedicated itself to the termination of the inherited anachronism that had so long retarded the nation’s progress, and crippled its pretensions to the leadership of the liberal forces of the globe. What was more, Lincoln had converted the war into a struggle for the rights of labor in the broadest sense.”24 According to Nevins:

The eminent cleric James Freeman Clark, visiting a contraband campaign Washington early in 1863, asked one Negro just from Virginia whether the slaves down there had heard of the proclamation. ‘Oh yes, massa! We-all knows about; only we darsen’t let on. We pretends not to know. I said to my ole massa, ‘What’s this Marse Lincoln is going to do…I hear he is going to cut ’em up awful bad. How is it, massa?’ I just pretended foolish, sort of.’ In the West the story was the same. The Cairo levees were black with fleeing slaves; Sherman wrote from Memphis that he had a thousand at work on the Memphis fortifications, and could send any number to St. Louis.25

President Lincoln’s Illinois colleague Isaac Arnold wrote: “The proclamation of emancipation did not change the local law in the insurgent states, it operated on the persons held as slaves; ‘all persons held as slaves are and henceforth shall be free.’ The law sanctioning slavery was not necessarily abrogated, hence the necessity for the amendment of the Constitution. The Supreme Court of the United States declared that: ‘When the armies of freedom found themselves upon the soil of slavery, they (and the President their commander) could do nothing less than free the poor victims whose enforced servitude was the foundation of the quarrel.”26

In his letter to a group of Unionists meeting in Springfield, Illinois on September 3, President Lincoln defended the Emancipation Proclamation against its critics: “But the proclamation, as law, either is valid, or is not valid. If it is not valid, it needs no retraction. If it is valid, it can not be retracted, any more than you can bring the dead can be brought to life. Some of you profess to think it’s retraction would operate favorably for the Union. Why better after the retraction, than before the issue? There was more than a year and a half of trial to suppress the rebellion before the proclamation issued, the last one hundred days of which passed under an explicit notice that it was coming, unless averted by those in revolt, returning to their allegiance. The war has certainly progressed as favorably for us, since it’s issue of the proclamation as before.”27

On December 9, 1863 President Lincoln’s Message to Congress was read in the House of Representatives. He wrote: “I shall not attempt to retract or modify the emancipation proclamation; nor shall I return to slavery any person who is free by the terms of that proclamation, or by any of the acts of Congress…..add.” Presidential aide John Hay was present to witness the reaction to the presidential message. “We watch the effect with great anxiety,” wrote Hay in his diary: “Whatever may be the results or the verdict of history the immediate effect of this paper is something wonderful. I never have seen such an effect produced by a public document. Men acted as if the millennium had come. [Zachariah] Chandler was delighted, [Charles] Sumner was beaming, while at the other political pole [James] Dixon and Reverdy Johnson said it was highly satisfactory. [John W.] Forney said ‘We only wanted a leader to speak the bold word. It is done and all can follow. I shall speak in my two papers tomorrow in a way to make these Presidential aspirants squirm.’ Henry Wilson came to me and laying his broad palms on my shoulders said ‘The President has struck another great blow. Tell him from me God Bless him.’ Hay’s diary continued:

In the House the effect was the same. [George] Boutwell was looking over it quietly & saying, It is a very able and shrewd paper. It has great points of popularity: & it is right.’ [Owen] Lovejoy seemed to see on the mountains the feet of one bringing good tidings. He said it was glorious. [“]I shall live he said to see slavery ended in America” [James] Garfield says, quietly, as he says things, “the President has struck a great blow for the country and himself.” [Francis W.] Kellogg of Michigan was superlatively enthusiastic. He said ‘The President is the only man. He is the great man of the century. There is none like him in the world. He sees more widely and more clearly than anybody.’

[U.S. Minister to Prussia Norman] Judd was there watching with his glittering eyes the effect of his great leader[‘]s word. He was satisfied with the look of things. Said [Owen]Lovejoy, Some of Lincoln’s friends disagreed with him for saying ‘a house divided &c.’ “I did” said Judd. “I told him if we had seen the speech we would have cut that out.” “Would you” said Lincoln. “In five years he is vindicated..”

Henry T. Blow said, “God Bless Old Abe. I am one of the Radicals who have always believed in the President.” He went on to talk with me about the feeling of the Missouri Radicals. That they must be reconciled to the President. That they are natural allies. That they have nowhere to go out of the Republican party, that a little proper treatment would heal all trouble as already a better feeling is developing. He thinks the promotion of [Peter] Osterhaus would have a good effect.

Horace Greeley went so far as to say it was ‘Devilish good!’

All day the tide of congratulation ran on. Many called to pay their personal respects. All seemed to be frankly enthusiastic. [William H.] Gurley of Iowa came and spent several hours talking matters over. He says there are but two or three points that can prevent the renomination of Mr[.] Lincoln: Gen[. Henry W.] Halleck: the Missouri business: Blair may be the weapons [sic] which in the hands of the Radical and reckless German element, may succeed in packing a convention against him.28

In their biography of Mr. Lincoln, Hay and John G. Nicolay wrote: “It is rare that so important a state paper had been received with such unanimous tokens of enthusiastic adhesion. However the leading Republicans in Congress may have been led later in the session to differ with the President, there was apparently no voice of discord raised on the day the message was read to both Houses. For a moment all factions in Congress seemed to be of one mind. One who spent the morning on the floor of Congress wrote on the same day: ‘Men acted as though the millennium had come. Chandler was delighted, Sumner was joyous, apparently forgetting for the moment his doctrine of State suicide; while at the other political pole [James] Dixon and Reverdy Johnson said the message was highly satisfactory. Henry Wilson said to the President’s secretary: ‘He has struck another great blow. Tell him for me, God bless him.’ The effect was similar in the House of Representatives. George S. Boutwell, who represented the extreme antislavery element of New England, said: ‘It is a very able and shrewd paper. It has great points of popularity, and it is right.’ Owen Lovejoy, the leading abolitionist of the West, seemed to see on the mountain the feet of one bringing good tidings. ‘I shall live,’ he said, ‘to see slavery ended in America.'”29

Footnotes

- Herbert Mitgang, The Fiery Trial: A Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 126.

- Allan Nevins, The Statesmanship of the Civil War, p. 131.

- Issac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 266.

- Allen C. Guelzo, “Seven-Score Years Ago…”, Washington Post, January 1, 2003, .

- Ralph Korngold, Thaddeus Stevens: A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great, p. 195-196 (February 24, 1863).

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 216.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Abraham Lincoln: A Press Portrait, p. 330 (Illinois Journal, January 6, 1863).

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 216-217.

- Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 359.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 217.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 240-241.

- Willard L. King, Lincoln’s Campaign Manager, p. 207-208.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 217.

- William K. Klingaman, Abraham Lincoln and the Road to Emancipation, 1861-1865, p. 288.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 63-65 (December 31, 1862).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 63-65 (January 19, 1863).

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Abraham Lincoln: A Press Portrait, p. 332-333 (London Times, January 15, 1863).

- Allan Nevins, The Statesmanship of the Civil War, p. 131.

- John Y. Simon Harold Holzer and William D. Pederson, editor, Lincoln, Gettysburg and the Civil War, p. 57 (Edna Greene Medford).

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom: Blacks in the Civil War, 1861-1865, p. 23.

- James M. McPherson, The Negro’s Civil War, p. 65.

- John Y. Simon Harold Holzer and William D. Pederson, editor, Lincoln, Gettysburg and the Civil War, p. 51 (Edna Greene Medford).

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, Volume II, p. 235-236.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, Volume II, p. 235-237.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, Volume II, p. 235-236.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 267.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 406-410 (Letter to James C. Conkling, August 26, 1863).

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 121-122 (December 9, 1863).

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume IX, p. 108.