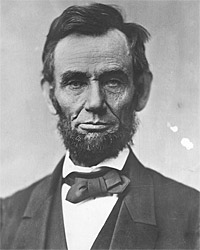

For much of the Civil War, Mr. Lincoln juggled conflicting pressures and politicians on the issue of slavery. But the movement toward emancipation of all black Americans was inexorable. After the Final Emancipation Proclamation was released on January 1, 1863, presidential aide John G. Nicolay wrote an anonymous newspaper editorial which concluded: “And for this New Year’s gift, the man who has wrought the work, amid the doubts of friends, the aspersions of foes, the clamors of faction, the cares of Government, the crises of war, the dangers of revolution, and the manifold temptations that beset moral heroes, Abraham Lincoln, the President of the United States, is entitled to the everlasting gratitude of a despised race enfranchised, the plaudits of a distracted country saved, and an inscription of undying fame in the impartial records of history.”1

Two years and one month later, Nicolay sent a note to President Lincoln at the White House: “Constitutional amendment just passed by 119 for to 56 votes against.”2 Nicolay was on Capitol Hill to witness passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution which outlawed slavery anywhere in the United States – not just in those areas engaged in the Confederate rebellion.

At the beginning of the War President Lincoln resisted “both the antislavery and the proslavery extremists,” wrote historian Richard N. Current. “On the one hand, he opposed the abolitionists of the Garrisonian type, ‘those who would shiver into fragments the Union of these States; tear to tatters its now venerated constitution; and even burn the last copy of the Bible, rather than slavery should continue a single hour.’ On the other hand, he opposed the propagandists of the Calhounian line, those ‘who, for the sake of perpetuating slavery, are beginning to assail and to ridicule the white-man’s charter of freedom – the declaration that ‘all men are created free and equal.'”3

Historian Current wrote: “Evil though slavery was, Lincoln tolerated it for at least three reasons. First, the Constitution gave the federal government no power to proceed against slavery within the states. In some states, slavery was already well established at the time the Constitution was adopted; these states would never have agreed to the new Union had they not had reason to believe that slavery would continue to be safe inside it. Thus the very Union that Lincoln loved had been made possible by forbearance with regard to this particular evil. Second, even if the federal government possessed the power to abolish slavery, and even if that power could be exercised without danger to the Union, abolition would create more problems than it would solve. Freeing the slaves would set loose millions of people who, with no experience in making their own way, would face the crippling handicap of deep and widespread prejudice. For the good of the Negroes as well as the whites, it seemed to Lincoln that slavery should be eliminated only very gradually. The Negroes, as they were freed, could be resettled outside the United States – in Africa, the West Indies, or Central America, where their color would be no bar to their future success and happiness. Third, there was no need to take positive action against slavery, for the institution would eventually die of its own weight if it was confined to the southern states. That was why the Founding Fathers could reconcile themselves to the continued presence of bondage in the land of the free. Lincoln, like the Fathers, was willing to wait.”4

Ronald C. White Jr. wrote in Lincoln’s Greatest Speech wrote: “Lincoln’s challenge as president was how to balance his opposition to slavery and his fidelity to the Constitution. He was aware that there was a certain truth in [William Lloyd] Garrison’s charge that the Constitution was a compromise document that allowed slavery in the South. Lincoln had, however, argued at Cooper Union in 1860 that the founders were united in opposing the spread of slavery to the new territories. He came to believe that the founders believed or hoped that slavery would one day become extinct.”5So did Mr. Lincoln.

Historian Hans L. Trefousse wrote: “It is true that Lincoln never, prior to 1862, advocated federal action to end slavery in the states where it existed. Constitutional obligations were important to him, and he hoped that putting an end to the expansion of the institution would in the end cause its demise in the South.”6 “It would do no good to go ahead, any faster than the country,” President Lincoln told the Rev. Charles Edwards Lester, himself an emancipation advocate. Mr. Lincoln made his comments after he reversed General John C. Frémont’s order of emancipation in Missouri in the summer of 1861: “I think [Massachusetts Senator Charles] Sumner and the rest of you would upset our applecart altogether if you had your way. We’ll fetch ’em; just give us a little time. We didn’t go into the war to put down slavery, but to put the flag back, and to act differently at this moment, would, I have no doubt, not only weaken our cause but smack of bad faith; for I never should have had votes enough to send me here if the people had supposed I should try to use my power to upset slavery. Why, the first thing you’d see, would be a mutiny in the army. No, we must wait until every other means has been exhausted. This thunderbolt will keep.”7

Mr. Lincoln’s thinking on freedom and slavery evolved during the war. Even as he was drafting the emancipation proclamation in the summer of 1862, he was trying out other ideas. Illinois Senator Orville Browning wrote in his diary on July 1, 1862.

“Immediately after breakfast went to the Presidents with Uri Manly. Saw the President alone, and had a talk with him in regard to the Confiscation bills before us. He read me a paper embodying his views of the objects of war, and the proper mode of conducting it in its relations to slavery. This, he told me, had sketched hastily with the intention of laying it before the Cabinet. His views coincided entirely with my own. No negroes necessarily taken and escaping during the war are ever to be returned to slavery – No inducement are to be held out to them to come into our lines for they come now faster than we can provide for them and are becoming an embarrassment to the government.

“At present none are to be armed. It would produce dangerous & fatal dissatisfaction in our army, and do more injury than good.

Congress has no power over slavery in the states, and so much of it as remains after the war is over will be in precisely the same condition that it was before the war began, and must be left to the exclusive control of the states where it may exist.8

President Lincoln was concerned about reaction in the Border States and the Army. Three days later on July 4, Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner repeatedly urged President Lincoln to adopt a policy of emancipation. “I would do it if I were not afraid that half the officers would fling down their arms and three more states would rise,” President Lincoln told Sumner.9 A few weeks later, Sumner quoted the President as telling him: “Wait – time is essential.”10

But the military necessities of putting down the rebellion pushed President Lincoln to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. President Lincoln said of the Emancipation Proclamation, “It is my last card, and I will play it and may win the trick.”11 But Mr. Lincoln did not believe that one card alone would win the war. He told Canadian doctor Alexander Milton: “I am glad you are pleased with the Emancipation Proclamation, but there is work before us yet; we must make that proclamation effective by victories over our enemies. It’s a paper bullet, after all, and of no account, except we can sustain it.”12 President Lincoln told New York Senator Edwin D. Morgan: “We are a good deal like the whalers who have been long on a chase. At last we have got our harpoon fairly into the monster, but we must now look how we steer, or with one flop of his tail, he will yet send us all into eternity.”13

Timing was indeed critical for the proclamation’s effectiveness. Mr. Lincoln told New Jersey War Democrat James M. Scovel, “I told you a year ago that Henry Ward Beecher and Horace Greeley gave me no rest because I would not free the Negroes. The time had not come.”14 After a meeting with Chicago ministers shortly before he issued the Draft Emancipation Proclamation in September 1862, President Lincoln said to them: “I have been much gratified with this interview. You have done your duty; I will try to do mine. In addition to what I have already said, there is a question of expediency as to time, should a proclamation be issued. Matters look dark just now. I fear that a proclamation on the heels of defeat would be interpreted as a cry of despair. It would come better, if at all, immediately after a victory. I wish I could say something to you more entirely satisfactory.”15

On the day he announced the Draft Emancipation Proclamation to the Cabinet, Mr. Lincoln told Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton: “Stanton, it would have been too early last spring.”16 After issuing the proclamation, President Lincoln told the Rev. John McClintock “Ah, Providence is stronger than either you or I. When I issued that proclamation, I was in great doubt about it myself. I did not think that the people had been quite educated up to it, and I feared its effects upon the border states. Yet I think it was right. I knew it would help our cause in Europe, and I trusted in God and did it.”17 President Lincoln had thought deeply about the potential implications of the Emancipation Proclamation. He responded to criticism of the impact of the Emancipation Proclamation on the war effort by telling Union Army Sergeant James M. Stradling in March 1863:

The proclamation was, as you state, very near to my heart. I thought about it and studied it in all its phases long before I began to put it on paper. I expected many soldiers would desert when the proclamation was issued, and I expected many who care nothing for the colored man would seize upon the proclamation as an excuse for deserting. I did not believe the number of deserters would materially affect the army. On other hand, the issuing of the proclamation would probably bring into the ranks many who otherwise would not volunteer.

After I had made up my mind to issue it, I commenced to put my thoughts on paper, and it took me many days before I succeeded in getting it into shape so that it suited me. Please explain to your comrades that the proclamation was issued for two reasons. The first and chief reason was this, I felt a great impulse moving me to do justice to five or six millions of people. The second reason was that I believed it would be a club in our hands with which we could whack the rebels. In other words, it would shorten the war. I believed that under the Constitution I had a right to issue the proclamation as a

“military necessity.”

President Lincoln was particularly concerned about the impact of his actions on the Border States. When Union General Egbert L. Viele told the President that blacks in Norfolk, Virginia did not understand that the Emancipation Proclamation did not liberate them, Mr. Lincoln replied: “This is the difficulty: we want to keep all that we have of the border states, those that have not seceded and the portions of those which we have occupied; and in order to do that, it is necessary to omit those areas I have mentioned from the effect of this proclamation.”18 Navy Secretary Gideon Welles recalled the President’s thinking: “A movement toward emancipation in the border states would, they believed, detach many from the Union cause and strengthen their apprehension. What had been done and what he had heard satisfied him that a change of policy in the conduct of the war was necessary and that emancipation of the slaves in the rebel states must precede that must precede that in the border states. The blow must fall first and foremost on them. Slavery was doomed. This war, brought upon the country by the slave-owners, would extinguish slavery, but the border states could not be induced to lead in that measure. They would not consent to be convinced or persuaded to take the first step.”19

Mr. Lincoln had long thought that the North and South shared responsibility for slavery. In a July 1862 conversation with the Rev. Elbert S. Porter, President Lincoln said “that one section was no more responsible than another for its original existence here, and that the whole nation having suffered from it, ought to share in efforts for its gradual removal.”20 The cause of the Civil War was clear – according to President Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address: “One eighth of the whole population were colored slaves, not distributed generally over the Union, but localized in the Southern part of it. These slaves constituted a peculiar and powerful interest. All knew that this interest was, somehow, the cause of the war. To strengthen, perpetuate, and extend this interest was the object for which the insurgents would rend the Union, even by war; while the government claimed no right to do more than to restrict the territorial enlargement of it. Neither party expected for the war, the magnitude, or the duration, which it has already attained. Neither anticipated that the cause of the conflict might cease with, or even before, the conflict itself should cease. Each looked for an easier triumph, and a result less fundamental and astounding.”21

Ronald C. White, Jr., wrote that this section of the Second Inaugural makes a clear allusion to President Lincoln’s “fidelity to the Constitution. The word ‘Constitution’ is never used in the address, but the nature and meaning of the Constitution are present throughout.” White noted that in President Lincoln’s First Inaugural, he had said: “I have no purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no legal right do so, and I have no inclination to do so.”22 Nevertheless, Mr. Lincoln understood that slavery was morally indefensible.

President Lincoln understood that the Civil War gave him power over slavery that the President did not otherwise possess. When black abolitionist Sojourner Truth told President Lincoln in October 1864 that he was the first American President to help American blacks, Mr. Lincoln responded: “And the only one who ever had such opportunity. Had our friends in the South behaved themselves, I could have done nothing whatever.”23 Abolitionist Moncure D. Conway reported that over two years earlier – well before the draft Emancipation Proclamation was issue – President Lincoln aid: “We grow in this direction daily, and I am not without hope that some great thing is to be accomplished. When the hour comes for dealing with slavery, I trust I shall be willing to act, though it costs my life, and, gentlemen, lives will be lost.”24

Historian K.C. Wheare wrote: “There is much in Lincoln’s attitude here that is puzzling. His attitude to slavery is perhaps not so puzzling as his attitude to the union. After all, as will have been appreciated from the account given so far, Lincoln’s attitude on slavery was consistent all through his political life. He opposed its extension in the Territories, but he opposed also interference with slavery in the state; and whenever he considered abolition, it was gradual and with compensation. He was on the slavery issue a moderate, not an abolitionist and not an extensionist. Yet, if this were so, when the states of the lower South seceded, why not let them? They were slaves states; Lincoln did not advocate interfering with slavery in them; outside the Union they could have no influence upon Union policy, no influence upon the Territories.”25

Mr. Lincoln’s opposition to slavery was constrained by the Constitution but his interpretation of his constitutional responsibilities also allowed him to act. “What, then, caused Abraham Lincoln, the nationalist, the narrowly focused, almost obsessive defender of the Union during the war’s first two years, to broaden his vision and become at last the Great Emancipator?” asked historian Kenneth M. Stamp. “It has hardly a role that he had anticipated. This remarkable transformation began sometime in the summer of 1863. By then the war had gone on too long, its aspect had become too grim, and the escalating casualties were too staggering for a man of Lincoln’s sensitivity to discover in that terrible ordeal no greater purpose than the denial of the southern claim to self-determination.”26

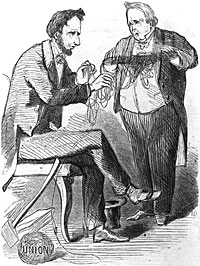

But the Constitution did not restrain proponents of abolition: “In the minds of many people there had been a crying need for the liberation of the slaves. Laborious efforts had been made to hasten the issuance by the President of the Emancipation Proclamation, but he was determined not to be forced into premature and inoperative measures,” wrote friend William H. Herndon. “Wendell Phillips abused and held him up to public ridicule from the stump in New England. Horace Greeley turned the batteries of the New York Tribune against him; and, in a word, he encountered all the rancor and hostility of his old friends the Abolitionists.”27 John Palmer Usher, who served first as Assistant Interior Secretary and later as Interior Secretary, wrote later:

Mr. Greeley was evidently dissatisfied with the explanation of Mr. Lincoln, and the Tribune teemed with complaints and criticisms of his administration, which very much annoyed him; so much so that he requested Mr. Greeley to come to Washington and make known in person his complaints, to the end that they might be obviated if possible. The managing editor of the Tribune came. Mr. Lincoln said:

“You complain of me. What have I done or omitted to do which has provoked the hostility of the Tribune?”

‘The reply was: ‘You should issue a proclamation abolishing slavery.”

Mr. Lincoln answered: ‘Suppose I do that. There are now 20,000 of our muskets on the shoulders of Kentuckians, who are bravely fighting our battles. Every one of them will be thrown down or carried over to the rebels.”

The reply was: ‘Let them do it. The cause of the Union will be stronger if Kentucky should secede with the rest than it is now.”

Mr. Lincoln answered: ‘Oh, I can’t think that!”28

Historian Gabor S. Boritt wrote: “The President did not intend to help perpetuate slavery – on the contrary. Yet he hoped that at least some conservative Northerners and liberal Southerners would so understand his proclamations. Indeed, the first concrete effect of his preliminary proclamation on the South was to start a bustle, in Union held areas, about sending representatives to Congress in Washington and so qualify for absolution from emancipation. Democratic Representative Daniel Voorhees of Indiana accordingly declared, with some justice, that the Republican chief’s strategy of incentives was ‘the grossest and most outrageous assault upon the freedom of the elective franchise.’ Of course he failed to take into account that this, as all the executive attempts to influence Southerners, was brought on by a vast civil war.”29

The war provided a reason, a need and an excuse for such interference. Jennifer Fleischner, who wrote a biography of Mary Todd Lincoln and her black seamstress and friend, Elizabeth Keckly, observed: “What [Frederick] Douglass called the ‘educating tendency’ of the war on Lincoln’s racial understanding would be reinforced by Lincoln’s encounters with dignified black men like Frederick Douglass; yet Lizzy’s presence in his family circle also likely contributed to his evolving comprehension of black life in America. By the time Douglass met with Lincoln, Lizzy had developed her own quiet relationship with the President. While combing his hair or sewing in the sitting room when he happened to enter, they sometimes fell into conversation, and like Douglass, she desired and treasured this powerful white man’s recognition.”30

Pennsylvania politician Alexander K. McClure, who frequently visited Mr. Lincoln at the White House, later wrote: “Lincoln treated the Emancipation question from the beginning as a very grave matter-of-fact problem to be solved for or against the destruction of slavery as the safety of the Union might dictate. He refrained from Emancipation for eighteen months after the war had begun, simply because he believed during that time that he might best save the Union by saving slavery, and had the development of events proved that belief to be correct he would have permitted slavery to live with the Union. When he became fully convinced that the safety of the government demanded the destruction of slavery, he decided, after the most patient and exhaustive consideration of the subject, to proclaim his Emancipation policy. It was not founded solely or even chiefly on the sentiment of hostility to slavery. If it had been, the proclamation would have declared slavery abolished in every State of the Union; but he excluded the slave States of Delaware, Maryland, and Tennessee, and certain parishes in Louisiana, and certain counties in Virginia, from the operation of operation of the proclamation, declaring, in the instrument that has now become immortal, that ‘which excepted parts are for the present left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.'”31

According to historian James M. McPherson, “One of the best arguments of [Frederick] Douglass and other abolitionists was that slavery was a source of strength to the Confederacy. Slaves worked in the fields and factories; slaves dug trenches and drove wagons for the Confederate army. Without their labor, the South would collapse, and the North could win the war. A proclamation of emancipation, said Douglass, would cripple the South by encouraging slaves to flee their masters and come over to the Northern side where freedom awaited them.”32

Presidential aide William O. Stoddard wrote for the New York Examiner after the Draft Emancipation Proclamation was issued in September 1862: “One victory, amoral one, has been gained by the President during the week that has passed, in sending out to the country and the world his Emancipation Proclamation. It was a bold movement, in face of many probabilities and some disagreeable certainties; and even now it depends upon those at the North who agree with it in principle, to show that its grand announcement of approaching liberation is not all ‘brutum fulmen.”33

A week later Stoddard wrote:”The President’s Emancipation Proclamation is having a greater effect at the South than even its friends anticipated. ‘It is thehit bird that flutters.’ Every report, from every source, would seem to indicate an immense sensation all over the regions now in rebellion. Further to exasperate the traitors is simply impossible; if then they are experiencing any large degree of new emotion, it must be that mixture of rage and fear which puzzles the brain of counsel, and unstrings the nerves of action.”34

After President Lincoln issued the Final Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, Stoddard wrote: “The President has been true to his declared policy, and we are now to see, as speedily as the course of events will permit, whether the eternal justice embodied in his Emancipation Proclamation will or will not add strength to the good cause in behalf of which it was promulgated.” Stoddard added: “It may be borne in mind that the action of the President does not propose to interfere with local laws, and deals only with those now held as bondsmen; but no man can doubt that the emancipation of this mass,this generation, provides free papers for all the millions yet unborn. Now let the armies press forward: every rebellious States that is held for thirty days only, is by that occupation forever deprived of all strength to originate new acts of treason. Vast regions which yield supplies to the rebellion would be powerless for that end, had the present state of things been created twelve months earlier. Only through their slaves do the rebels keep their forces in the field – in so far as they are deprived of them, must their ability fail them.”

The extermination of slavery during the Civil War was slow but steady. Historian Harry V. Jaffa wrote: “This grudging record of the ‘legal extinction’ of any possibility of slavery in United States territories may also, with charity, be allowed to pass with little comment. What should not be passed over, however, is the fact that in June 1862, six months after the meeting of the first regular session of the first Congress sitting during the presidency of Abraham Lincoln, slavery in the territories of the United States ‘then existing or thereafter to be formed or acquired’ was prohibited. If this constituted an abandonment of the principles of the campaign of 1858, if this was not a consummation of everything Lincoln had fought for that fateful summer, then words have no meaning.”35

President Lincoln was especially sensitive to the loyalty of and attitudes in the Border States. These states were positioned at points along vital rivers and rail networks that the Union needed to control.

Historian Hans L. Trefousse wrote: “While president, Lincoln, for reasons of political necessity, emphasized that the war was fought, not for the abolition of slavery, but for the preservation of the Union; he never wavered from his conviction that slavery was wrong. In view of the fact that he had been elected by a minority of some 39 percent of the voters, most of whom had no sympathy with abolitionism, and that he had to retain their loyalty, he could not emphasize his antislavery convictions. This was especially true because he was anxious to retain the border slave states – he is reputed to have said that he hoped God was on his side but he must have Kentucky – and any antislavery move would have heightened the danger of further secession.”36

Union came first. Historian James M. McPherson wrote: “Although restoration of the Union remained his first priority, the abolition of slavery became an end as well as a means, a war aim virtually inseparable from Union itself. The first step in making it so came in the Emancipation Proclamation, which Lincoln pronounced ‘an act of justice’ as well as a military necessity. Of course, the border states, along with Tennessee and small enclaves elsewhere in the Confederate states, were not covered by the Proclamation because they were under Union control and not at war with the United States and thus exempt from an Executive action that could legally be based only on the President’s war powers.”37 Presidential aide William O. Stoddard wrote in an anonymous newspaper dispatch at the end of August 1863:

“The Emancipation policy, and the arming of the black men – the two great measures of the Administration – are swiftly vindicating the wisdom of their author. In the opinion of several of our best and foremost generals – old Democrats, too – they have been the heaviest blows yet given to our enemies. Such measures, for which there could not possible be found any adequate precedent, must ever be judged by their results, and the results are presenting themselves each day for our examination. How many troublesome questions will be settled at once and forever by that same Proclamation, can only be understood by the men who had command in rebel districts before it became the law of the land, and who honestly endeavored to carry out ‘the compromises of the Constitution,’ in the management of their commands.

Said one gentleman, weak in the faith, and with the egg-shell of State Rights (in rebel States) still upon his head, to another, “But if you conquer all these States, or if they now voluntarily return, what course will you take with the slaves? Say in North Carolina?” “My dear sir,” was the reply, “I was not aware that there were any slaves in North Carolina. The black people of that and other rebellious States have been freemen in the eye of our law this long time.”38

A year later in August 1864, at a point of political peril for President Lincoln, he had an extended conversation with former Wisconsin Governor Alexander W. Randall and journalist Joseph T. Mills. Mills recorded the results of the interview in his diary. President Lincoln reviewed his thinking about the state of the war and the contributions of black soldiers to the war effort:

The President was free & animated in conversation. I was astonished at his elasticity of spirits. Says Gov Randall, why cant you Mr P. seek some place of retirement for a few weeks. You would be reinvigorated. Aye said the President, 3 weeks would do me no good – my thoughts my solicitude for this great country follow me where ever I go. I don’t think it is personal vanity, or ambition – but I cannot but feel that the weal or woe of this great nation will be decided in the approaching canvas. My own experience has proven to me, that there is no program intended by the democratic party but that will result in the dismemberment of the Union. But Genl McClellan is in favor of crushing out the rebellion, & he will probably be the Chicago candidate. The slightest acquaintance with arithmetic will prove to any man that the rebel armies cannot be destroyed with democratic strategy. It would sacrifice all the white men of the north to do it. There are now between 1 & 200 thousand black men now in the service of the Union. These men will be disbanded, returned to slavery & we will have to fight two nations instead of one. I have tried it. You cannot concilliate [sic] the South, when the mastery & control of millions of blacks makes them sure of ultimate success. You cannot conciliate the South, when you place yourself in such a position, that they see they can achieve their independence. The war democrat depends upon concillation [sic]. He must confine himself to that policy entirely. If he fights at all in such a war as this he must economise life & use all the means which God & nature puts in his power. Abandon all the posts now possessed by black men surrender all these advantages to the enemy, & we would be compelled to abandon the war in 3 weeks. We have to hold territory. Where are the war democrats to do it. The field was open to them to have enlisted & put down this rebellion by force of arms, by concilliation [sic], long before the present policy was inaugurated. There have been men who have proposed to me to return to slavery the black warriors of Port Hudson & Olustee to their masters to conciliate the South. I should be damned in time & in eternity for so doing. The world shall know that I will keep my faith to friends & enemies, come what will. My enemies say I am now carrying on this was for the sole purpose of abolition. It is & will be carried on so long as I am President for the sole purpose of restoring the Union. But no human power can subdue this rebellion without using the Emancipation lever as I have done. Freedom has given us the control of 200 000 able bodied men, born & raised on southern soil. It will give us more yet. Just so much it has sub[t]racted from the strength of our enemies, & instead of alienating the south from us, there are evidences of a fraternal feeling growing up between our own & rebel soldiers. My enemies condemn my emancipation policy. Let them prove by the history of this war, that we can restore the Union without it. The President appeared to be not the pleasant joker I had expected to see, but a man of deep convictions & an unutterable yearning for the success of the Union cause. His voice was pleasant – his manner earnest & cordial. As I heard a vindication of his policy from his own lips, I could not but feel that his mind grew in stature like his body, & that I stood in the presence of the great guiding intellect of the age, & that those huge Atlantian shoulders were fit to bear the weight of mightiest monarchies. His transparent honesty, his republican simplicity, his gushing sympathy for those who offered their lives for their country, his utter forgetfulness of self in his concern for his country, could not but inspire me with confidence, that he was Heavens instrument to conduct his people thro this red sea of blood to a Canaan of peace & freedom.39

Massachusetts Senator Henry Wilson wrote of meeting President Lincoln in those same highly confused days: “He spoke of the pressure upon him, of the condition of the country, of the possible action of the coming Democratic Convention and of the uncertainty of the election in tones of sadness. After discussing for a long time these matters, he said with great calmness and firmness, – ‘I do not know what the result may be, we may be defeated, we may fail, but we will go down with our principles. I will not modify, qualify nor retract my proclimation [sic], nor my Letter [regarding the requirements for peace negotiations].’ I can never forget his manner, tones, nor words nor cease to feel that his firmness, amid the pressure of active friends, saved our cause in 1864.”40

Mr. Lincoln may not have intended at the outbreak of the Civil War to liberate all the country’s black residents from the yoke of slavery, but with the passage of the 13th Amendment to the Constitution on January 31, 1865, that is what he accomplished. Lincoln’s legal colleague and friend, William H. Herndon, wrote in his biography of Mr. Lincoln: “I believe Mr. Lincoln wished to go down in history as the liberator of the black man. He realized to its fullest extent the responsibility and magnitude of the act, and declared it was ‘the central act of his administration and the great event of the nineteenth century.’ Always a friend of the negro, he had from boyhood waged a bitter unrelenting warfare against his enslavement. He had advocated his cause in the courts, on the stump, in the Legislature of his State and that of the nation, and, as if to crown it with a sacrifice, he sealed his devotion to the great cause of freedom with his blood.”41

Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass did not begin the war as an admirer of Mr. Lincoln, but Douglass became one. Douglass gave a speech 11 years after Mr. Lincoln’s death in which he said that “President Lincoln was a white man, and shared the prejudices common to his countrymen towards the colored race. Looking back to his times and to the condition of his country, we are compelled to admit that this unfriendly feeling on his part may be safely set down as one element of his wonderful success in organizing the loyal American people for the tremendous conflict before them, and bringing them safely through that conflict. His great mission was to accomplish two things: first, to save his country from dismemberment and ruin; and second, to free his country from the great crime of slavery. To do one or the other, or both, he must have the earnest sympathy and the powerful cooperation of his loyal fellow countrymen. Without this primary and essential condition to success his efforts must have been vain and utterly fruitless. Had he put the abolition of slavery before the salvation of the Union, he would have inevitably driven from him a powerful class of the American people and rendered resistance to rebellion impossible. Viewed from the genuine abolition ground, Mr. Lincoln seemed tardy, cold, dull and indifferent; but measuring him by the sentiment of his country, a sentiment he was bound as a statesman to consult, he was swift, zealous, radical and determined.”42

Footnotes

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 102 (January 2, 1863).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, With Lincoln in the White House: Letters, Memoranda, and Other Writings of John G. Nicolay, 1860-1865, p. 172 (January 31, 1865).

- Richard Nelson Current, The Political Thought of Abraham Lincoln, p. xix.

- Richard Nelson Current, The Political Thought of Abraham Lincoln, p. xvi.

- Ronald C. White, Jr., Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural, p. 95.

- Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh, editor, The Price of Freedom: Slavery and the Civil War, Volume I, p. 319 (Hans L. Trefousse, “Lincoln and Race Relations”).

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 295 (from Charles Edwards Lester, Life and public Services of Charles Sumner, pp. 359-360).

- Theodore Calvin Pease, editor, Orville Hickman Browning, Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, Volume I, p. 555 (July 1, 1862).

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 434 (Letter from Charles Sumner to John Bright, August 5, 1862).

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 435 (Letter from Charles Sumner to the Duchess of Argyll, August 11, 1862).

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 360 (Conversation with Edwards Pierrepont and James S. Wadsworth).

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 387.

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, p. 75.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 394.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 354.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 417.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 314.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 455.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 470.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 367-368 (Sermon preached in April 16, 1865).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VIII, p. 332-333 (March 4, 1865).

- Ronald C. White, Jr., Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural, p. 94-95.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 116 (Sacramento Union, December 14, 1864).

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 118 (New York Tribune, August 30, 1885).

- Don E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Dwight Lowell Dumond, The Leadership of Abraham Lincoln, p. 183 (K.C. Wheare, Lincoln’s Devotion to the Union, Intense and Supreme).

- Gabor S. Boritt, editor, Lincoln the War President, p. 140 (Kenneth M. Stamp, “The United States and National Self-determination”).

- William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 442.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 87-88 (John P. Usher).

- Gabor S. Boritt, Lincoln and the Economics of the American Dream, p. 257.

- Jennifer Fleischner, Mrs. Lincoln and Mrs. Keckly: The Remarkable Story of the Friendship between a First Lady and Former Slave, p. 263.

- Alexander K. McClure, Lincoln and Men of War-Times, p. 107.

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 15-16.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 107 (New York Examiner, October 3, 1862).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 112-113 (New York Examiner, October 9, 1862).

- Harry V. Jaffa, Crisis in the House Divided, p. 402.

- Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh, editor, The Price of Freedom: Slavery and the Civil War, Volume I, p. 319-320 (Hans L. Trefousse, “Lincoln and Race Relations”).

- Gabor S. Boritt, editor, Lincoln the War President, p. 54-55 (James M. McPherson, “Lincoln and the Strategy of Unconditional Surrender”).

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Dispatches from Lincoln’s White House: The Anonymous Civil War Journalism of Presidential Secretary William O. Stoddard, p. 167-168 (August 31, 1863).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 506-507 (August 19, 1864).

- Douglas L. Wilson and Rodney O. Davis, editor, Herndon’s Informants: Letters, Interviews and Statements about Abraham Lincoln, p. 562 (Letter from Henry Wilson to William H. Herndon, May 30, 1867).

- William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 443 (Quote is from Henry J. Raymond, Life and Public Services of Abraham Lincoln, p.764).

- Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, p. 485 (Speech at the Freedmen’s Monument, April 16, 1876).

Visit

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

William O. Stoddard (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

William O. Stoddard (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Henry Wilson (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Civil War Search Directory