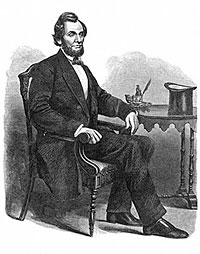

President Lincoln took an active role in recruiting congressional supporters for passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in January 1865. Historian Allen C. Guelzo wrote: “This time, the Radicals could scarcely oppose him, and so the amendment offered him the rare opportunity to seize the initiative from them. But resistance could certainly be anticipated from Northern Democrats and border-state hold-outs. So, the secretaries were sent on their usual discreet embassies to unsure congressmen, while the more truculent border-staters were brought to the White House for personal interviews with the president.”1 Historian Phillip S. Paludan wrote that “Lincoln had the war on his mind and firmly believed that attacking slavery undermined the rebellion. The weight of congressional majorities, including Democratic votes, and especially the passage of the amendment by slaves states would further erode the morale of the Confederacy.”2

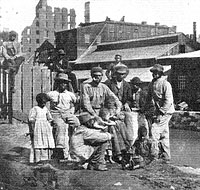

Contemporary journalist Noah Brooks wrote: “In the earlier months of the same Congress, in 1864, the measure had failed to receive the two thirds vote of the House necessary for its passage; and Representative Ashley of Ohio, who had then changed his vote in order that he might move a reconsideration, gave notice that he would call up the constitutional amendment on January 6, 1865. The debate ran on fitfully for the remainder of that month, and whenever it was noised abroad that the constitutional amendment to abolish slavery would come up in the House, the galleries were thronged to overflowing, and the speeches were listened to with great intentness. But to the very last day it was feared that the necessary two thirds vote could not be obtained. Although West Virginia, Missouri, Arkansas, Maryland, and Louisiana had by that time accepted the situation, and had adopted measures looking to the immediate emancipation of slaves, there were not a few men in the House of Representatives who opposed the constitutional amendment. William S. Holman and George H. Pendleton, from the Northern States, were among those who voted against it.”3

One key target of presidential persuasion was Missouri, according to Lincoln biographer Isaac Arnold, who was serving in the House of Representatives from Illinois at the time:

Mr. Lincoln hoped to induce some of the border state members, and war democrats who had at the last session voted against the proposition, to change their votes. To this end he sought interviews with them, and urged them to vote for the amendment. Among them was Mr. [James S.] Rollins, a distinguished member of Congress from Missouri, and a warm personal friend. Mr. Rollins says:

The President had several times in my presence expressed his deep anxiety in favor of the passage of this great measure. He and others had repeatedly counted votes in order to ascertain, as far as they could, the strength of the measure upon a second trial in the House. He was doubtful about its passage, and some ten days or two weeks before it came up for consideration in the House, I received a note from him, written in pencil on a card, while sitting at my desk in the House, stating that he wished to see me, and asking that I call on him at the White House. I responded that I would be there the next morning at nine o’clock. I was prompt in calling upon him and found him alone in his office. He received me in the most cordial manner, and said in his usual familiar way: ‘Rollins, I have been wanting to talk to you for sometime about the thirteenth amendment proposed to the Constitution of the United States, which will have to be voted on now, before a great while.’ I said: ‘Well, I am here, and ready to talk upon that subject.’ He said: ‘You and I were old whigs, both of us followers of that great statesman, Henry Clay, and I tell you I never had an opinion upon the subject of slavery in my life that I did not get from him. I am very anxious that the war should be brought to a close at the earliest possible date, and I don’t believe this can be accomplished as long as those fellows down South can rely upon the border states to help them; but if the members from the border states would unite, at least enough of them to pass the thirteenth amendment to the Constitution, they would soon see that they could not expect much help from that quarter, and be willing to give up their opposition and quit their war upon the government; this is my chief hope and main reliance to bring the war to a speedy close, and I have sent for you as an old whig to come and see me, that I might make an appeal to you to vote for this amendment. It is going to be very close, a few votes on way or the other will decide it.’

To this I responded: ‘Mr. President, so far as I am concerned you need not have sent for me to ascertain my views on this subject, for although I represent perhaps the strongest slave district in Missouri, and have the misfortune to be one of the largest slave-owners in the county where I reside, I had already determined to vote for the thirteenth amendment.’ He arose from his chair, and grasping me by the hand, gave it a hearty shake, and said: ‘I am most delighted to hear that.’

He asked me how many more of the Missouri delegates in the House would vote for it. I said I could not tell; the republicans of course would; General Loan, Mr. Blow, Mr. Boyd, and Colonel McClurg. He said: ‘Won’t General Price vote for it? He is a good Union man.’ I said I could not answer. ‘Well, what about Governor King?’ I told him I did not know. He then asked about Judges Hall and Norton. I said they would both vote against it, I thought.

‘Well,’ he said, ‘are you on good terms with Price and King?’ I responded in the affirmative, and that I was on easy terms with the entire delegation. He then asked me if I would not talk with those who might be persuaded to vote for the amendment, and report to him as soon as I could find out what the prospect was. I answered that I would do so with pleasure, and remarked at the same time, that when I was a young man, in 1848, I was the whig competitor of King for Governor of Missouri and as he beat me very badly, I thought now he should pay me back by voting as I desired him on this important question. I promised the President I would talk to this gentleman upon the subject. He said: ‘I would like you to talk to all the border state men whom you can approach properly, and tell them of my anxiety to have the measure pass; and let me know the prospect of the border state vote,” which I promised to do. He again said: ‘The passage of this amendment will clinch the whole subject; it will bring the war, I have no doubt, rapidly to a close.’4

Other targets of opportunity included some Democratic congressmen from New Jersey. But there were limits to what President Lincoln could or would do. Historian Roy P. Basler wrote: “The delegation in Congress from New Jersey also figured in these private maneuvers, when representative James M. Ashley of Ohio, urged Lincoln’s Secretary Nicolay on January 18, 1865, that the Camden & Amboy Railroad interest had promised Ashley ‘that if he would help postpone the Raritan railroad bill over this session they would in return make the New Jersey Democrats help about the [Thirteenth] Amendment, either by their votes or absence.’ Senator Sumner was the proponent of the Raritan bill, however, and when Ashley had asked him to drop it for this session Sumner did not agree, because he said he thought the amendment would pass anyway. Ashley thought Sumner had other motives; namely, that the amendment would fail and then Sumner’s resolution containing the phrase ‘all persons are equal before the law’ could be reintroduced and passed. Nicolay continued, ‘Ashley therefore desired the President to send for Sumner, and urged him to be practical and secure the passage of the amendment in the manner suggested by Mr. Ashley.”5

Basler wrote: “When Nicolay told Lincoln of Ashley’s proposal, the President replied, ‘I can do nothing with Mr. Sumner in these Matters. While Mr. Sumner is very cordial with me, he is making his history in an issue with me on this very point. He hopes to succeed in beating the President so as to change this Government from its original form and make it a strong centralized power.’ Then calling Mr. Ashley into the room, the President said to him, I think I understand Mr. Sumner; and I think he would be all the more resolute in his persistence on the points which Mr. Nicolay has mentioned to me if he supposed I were at all watching his course on this matter.”6 Noted historian Phillip S. Paludan: “Lincoln said he could not influence Sumner with such assurances – but only because of Sumner’s peculiar commitments, not because this kind of trading was not right.”7

New Jersey was indeed critical to passage, according to historian Roy P. Basler: “Such were the business pressures, and private personal motives, of some representatives when the historic amendment came to a roll-call vote in the House of representatives on January 31, 1865. Of the five New Jersey representatives, for example, the single Republican John F. Starr voted yea; two Democrats, Andrew J. Rogers and George Middleton, abstained; one Democrat, William G. Steele, and one Constitutional Union Party representative, Nehemiah Perry, voted nay. The Amendment passed with 119 yeas, 56 nays, and 8 abstaining. Thus the eight members not voting, including the two from New Jersey, secured the amendment’s passage.”8

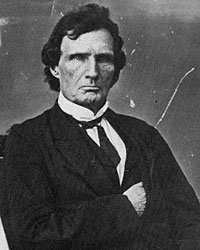

Pennsylvania Congressman Thaddeus Stevens was a firm supporter of the amendment and a man who did not place scruples in the way of his principles. But Stevens commented about President Lincoln’s action: “The greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America.”9 Ohio Congressman Samuel S. Cox, a Democratic opponent of the amendment, denounced a “fund which was said to be ready and freely used for corrupting members. Can anything be conceived more monstrous than this attempt to amend the Constitution upon such a human and glorious theme, by the aid of the lucre of office-holders?”10

However, according to historian Michael Vorenberg: “For all the backroom bargaining that took place in the days before the final vote on the amendment, it turns out that very few actual deals were struck – either by Lincoln or by anyone else. Most of those who were rewarded for their vote already had planned to support the amendment even before the lobbyists entered the fray. Perhaps their decision came from principle, perhaps it came from thepossibility of future patronage. But in only a few cases does a clear, promised incentive seem to have been involved, and in those cases, the opposition member usually abstained instead of voting for the amendment. Certainly there was no outright bribery. One Washington insider told the story that the New York lobbyists for the amendment controlled a $50,000 fund, but that after the amendment had been adopted, only $27.50 had been spent, all for incidental expenses only, not for bribes. ‘Good lord,’ one of them exclaimed, ‘that isn’t the way they do things at Albany!'”11

Meanwhile, according to Lincoln biographers John G. Nicolay and John Hay, a mighty flood of public opinion, overleaping old barriers and rushing into channels” was being felt in Congress. “The Democratic party did not and could not shut its eyes to the accomplished facts. ‘In my judgment,’ said William S. Holman of Indiana, ‘the fate of slavery is sealed. It dies by the rebellious hand of its votaries, untouched by the law. Its fate is determined by the war; by the measures of the war; by the results of the war. These, sire, must determine it, even if the Constitution were amended.’ He opposed the amendment, he declared, simply because it was unnecessary. Though few other Democrats were so frank, all their speeches were weighed down by the same consciousness of a losing fight a hopeless cause.”12 The House debate on passage of the Amendment was lively:

- Daniel W. Voorhees, an Indiana Democrat, opposed passage: “When the sky shall again be clear over our heads, a peaceful sun illuminating the land, and our great household of states all at home in harmony once more, then will be the time to consider what changes, if any, this generation desire to make in the work of Washington, Madison and the revered sages of our antiquity.”13

- John Kasson, Iowa Republican, said: “I would rather stand solitary, with my name recorded for this amendment, than to have all the honors which could be heaped upon me by any party in opposition to this proposition.”

- Frederick Woodbridge, Vermont Republican: “I want this resolution to pass, and then, when it (the war) does end, the beautiful statue of liberty which now crowns the majestic dome above our heads may look north and south, east and west, upon a free nation, untarnished by aught inconsistent with freedom; redeemed, regenerated, and disenthralled by the genius of universal emancipation.”14

- James S. Rollins, Missouri Constitutional Unionist slaveowner: “The convention which recently assembled in my state, I learned from a telegram a morning or two ago, had adopted an amendment to our present state constitution, for the immediate emancipation of all the slaves in the state. I am no longer the owner of a slave, and I thank God for it. If the giving up of my slaves without complaint shall be a contribution upon my part, to promote the public good, to uphold the Constitution of the United States, to restore peace and preserve this Union, if I had owned a thousand slaves, they would most cheerfully have been given up. I say with all my heart, let them go; but let them not go without a sense of feeling and a proper regard on my part for the future of themselves and their offspring.”15

- George H. Pendleton, Democratic Minority Leader and 1864 Democratic candidate for Vice President: “Let him be careful lest when the passions of these times be passed away and the historian shall go back to discover where was the original infraction of the Constitution, he may find that sin lies at the door of others than the people now in arms.”16

- Future President James Garfield, an Ohio Republican congressman who had succeeded abolitionist Joshua Giddings, delivered a speech in response to Democratic Congressman George Pendleton, who had been the Democratic candidate for Vice President in 1964: “Who does not remember that thirty years ago, a short period in the life of a nation, but little could be said with impunity in these halls on the subject of slavery? How well do gentlemen here remember the history of that distinguished predecessor of mine, Joshua R. Giddings, lately gone to his rest, who, with his forlorn hope of faithful men, took his life in his hands, and in the name of justice protested against the great crime, and who stood bravely in his place until his until his white locks, like the plume of Henry of Navarre, marked where the battle of freedom raged fiercest? We can hardly realize that this is the same people, and these the same halls, where now scarcely a man can be found who will venture to do more than falter out an apology for slavery, protesting at the same time that he has no love for the dying tyrant. None, I believe, but that man of more than supernal boldness from the city of New York [Mr. Fernando Wood] has ventured this session to raise his voice in favor of slavery for its own sake. He still sees in its features the reflection of divinity and beauty, and only he. ‘How art thou fallen from heaven, O Lucifer, son of the morning? How art thou cut down to the ground, which didst weaken the nations!’ Many mighty men have been slain by thee; many proud ones have humbled themselves at thy feet! All along the coast of the political sea they lie like stranded wrecks, broken on the headlands of freedom. How lately did its advocates with impious boldness maintain it as ‘God’s own,’ to be venerated and cherished as divine. It was another and higher form of civilization. It was the holy evangel of America, dispensing its blessings to the wilderness of the West. In its mad arrogance it lifted its hands to strike down the fabric of the Union, and since that fatal day, it has been a fugitive and a vagabond upon the earth, and like the spirit that Jesus cast out, it has since then been ‘seeking rest, and finding none.'”17

Stevens’ fellow congressman, Isaac Arnold, wrote of the final debate on January 13, 1865: ” And now, on the 13th of January, came Thaddeus Stevens, Chairman of the Committee of Ways and Means, and the recognized leader of the House, to close the debate. As he came limping with his club foot along down the aisle from his committee room, the members gathered thickly around him. He was tall and commanding in person, and although venerable with years, his form was unbent and his intellect undimmed. The galleries had already been filled with the most distinguished people in Washington. As the word ran through the Capitol that Stevens was speaking on the Constitutional Amendment, senators came over from the Senate, lawyers and judges from the court rooms, and distinguished soldiers and citizens filled every available seat, to hear the eloquent old man speak on a measure that was to consummate the warfare of forty years against slavery.” Stevens biographer Fawn M Brodie wrote that Stevens’ discourse “was short, like all of Stevens’ speeches, and more reflective than argumentative:18

From my earliest youth I was taught to read the Declaration and to revere it sublime principles. As I advanced in life and became somewhat enabled to consult the writings of great men of antiquity, I found in all their works which have survived the ravages of time and come down to the present generation, one unanimous denunciation of tyranny and of slavery, and eulogy of liberty. Homer, Aeshylus the Greek tragedian, Cicero, Hesiod, Virgil, Tacitus, and Sallust, in immortal language, all denounced slavery as a thing which took away half the man and degraded human beings, and sang peans in the noblest strings to the goddess of

When, fifteen years ago, I was honored with a seat in this body, it was dangerous to talk against this institution, a danger which gentlemen now here will never be able to appreciate. Some of us, however, have experienced it; my friend from Illinois on my right [Mr. Washburne] has. And yet, sir, I did not hesitate, in the midst of bowie knives and revolvers, and howling demons upon the other side of the House to stand here and denounce this infamous institution in language which possibly now, on looking at it, I might deem intemperate, but which I then deemed necessary to rouse the public attention, and cast odium upon the worst institution upon earth, one which is a disgrace to man, and would be an annoyance to the infernal spirits…

I recognized and bowed to a provision in that Constitution which I always regarded as its only blot…Such, sir, was my position…not disturbing slavery where the Constitution protected it, but abolishing it wherever we had the constitutional power, and prohibiting its further expansion. I claimed the right then, as I claim it now, to denounce it everywhere…

We have suffered for slavery more than all the plagues of Egypt. More than the first born of every household has been taken. We still harden our hearts, and refuse to let the people go. The scourge still continues, nor do I expect it to cease until we obey the behests of the Father of men. We are about to ascertain the national will by an amendment to the Constitution. If the gentlemen opposite will yield to the voice of God and humanity and vote for it, I verily believe the sword of the destroying angel will be stayed, and this people be re-united. If we still harden our hearts, and blood must still flow, may the ghosts of the slaughtered victims sit heavily upon the souls of those who cause it.”19

Footnotes

- Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, p. 401.

- Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln, p. 301.

- Herbert Mitgang, editor, Washington, D.C., in Lincoln’s Time: A Memoir of the Civil War Era by the Newspaperman Who Knew Lincoln Best: Noah Brooks, p. 184-185.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 358-359.

- Roy P. Basler, A Touchstone for Greatness, p. 200.

- Roy P. Basler, A Touchstone for Greatness, p. 200.

- Phillip Shaw Paludan, The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln, p. 301.

- Roy P. Basler, A Touchstone for Greatness, p. 200-201.

- Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, p. 401.

- Samuel S. Cox, Three Decades of Federation Legislation, p. 329.

- Charles M. Hubbard, editor, Lincoln Reshapes the Presidency, (Michael Vorenberg,“A King’s Cure, A King’s Style: Lincoln, Leadership, and the Thirteenth Amendment”).

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume X, p. 82-83.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 360.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 360.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 360.

- Ralph Korngold, Thaddeus Stevens: A Being Darkly Wise and Rudely Great, p. 230.

- Isaac N. Arnold, The Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 363.

- Fawn M. Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, p. 203.

- Fawn M. Brodie, Thaddeus Stevens: Scourge of the South, p. 203-204 ((From Congressional Globe, 38 Cong. 2 session, January 13, 1865, pp. 265-266).

Visit

Isaac Arnold (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Isaac Arnold (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Schuyler Colfax (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Charles A. Dana (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Charles A. Dana (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Edwin D. Morgan (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Edwin D. Morgan (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Thaddeus Stevens (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)