Thursday, January 1, 1863, was a bright crisp day in the nation’s capital. The previous day had been a strenuous one for the President, but New Year’s Day was to be even more strenuous. So he rose early. There was much to do, not the least of which was to put the finishing touches on the Proclamation. Before he could begin, the troubled General Ambrose E. Burnside, who had led the ill-fated Fredericksburg campaign, called at the White House,” wrote historian John Hope Franklin.1 Burnside thought he should be relieved of command – and that General-in-Chief Henry Halleck and Secretary of War Edwin Stanton should be as well. It was a major distraction that required all of the President’s diplomatic powers.

Early that morning, General Burnside brought plans for a new military advance against the forces of Confederate General Robert E. Lee in Virginia. He also thought he should be relieved of command – and that General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck and Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton should be dismissed as well. Soon, Halleck and Stanton also arrived at the White House. Halleck himself was non-committal about Burnside’s plans, refusing to provide definitive advice about military strategy.

President Lincoln grew frustrated and wrote a blunt letter that was delivered to General Halleck later in the day: “Gen. Burnside wishes to cross the Rappahannock with his army, but his Grand Division commanders all oppose the movement. If in such a difficulty as this you do not help, you fail me precisely in the point for which I sought your assistance. You know what Gen. Burnside’s plan is; and it is my wish that you go with him to the ground, examine it as far as practicable, confer with the officers, getting their judgment, and ascertaining their temper, in a word, gather all the elements for forming a judgment of your own; and then tell Gen. Burnside that you do approve, or that you do notapprove his plan. Your military skill is useless to me, if you will not do this.”2 General Halleck was offended. General Burnside was still indignant at the interference of his military subordinates. This general tempest was a major distraction that required all of the President’s tact to handle…while diplomats and generals were gathering to give him their New Years’ Day greetings.

According to contemporary journalist Ben Perley Poore, “”New Year’s Day was fair and the walking dry, which made it an agreeable task to keep up the Knickerbocker practice of calling on officials and lady friends. …At eleven o’clock all officers of the army in the city assembled at the War Department, and headed by Adjutant-General Thomas and General Halleck, proceeded to the White House, where they were severally introduced to the President. The officers of the navy assembled at the Navy Department at the same time, and headed, by Secretary Welles and Admiral Foote, also proceeded to the President’s. The display of general officers in brilliant uniforms was an imposing sight, and attracted large crowds. The foreign Ministers, in accordance with the usual custom, also called on the President, and at twelve o’clock the doors were opened to the public, who marched through the hall and shook hands with Mr. Lincoln, to the music of the Marine Band, for two or three hours. Mrs. Lincoln also received ladies in the same parlor with the President.”3

Historian Allen C. Guelzo wrote: “For Lincoln, any second thoughts or reconsiderations were understood to be out of his hands. On New Year’s Day, Robert Lincoln remembered, ‘my mother and I went in to his study, my mother inquiring in her quick, sharp way, ‘Well what do you intend doing?’ Lincoln simply looked heavenwards and replied, “I am under orders, I cannot do otherwise.”4 President Lincoln completed work on the Emancipation Proclamation in his office and then sent it to the State Department for its official calligraphy. It was brought to his office at 10:45 in the morning and signed by the President. But he did not like the superscription which read: In testimony whereof I have hereunto set my name and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.” The President preferred “hand” to “name” and asked Secretary of State William Seward to prepare a new copy for his signature. Presidential aides John G. Nicolay and John Hay wrote:

It is a custom in the Executive Mansion to hold on New Year’s Day an official and public reception, beginning at eleven o’clock in the morning, which keeps the President at the post in the Blue Room until two in the afternoon. The hour for this reception came before Mr. Lincoln had entirely finished revising the engrossed copy of the proclamation, and he was compelled to hurry away from his office to friendly handshaking and festal greeting with the rapidly arriving official and diplomatic guests. The rigid laws of etiquette held him to this duty for the space of three hours. Had actual necessity required it, he could of course have left such mere social occupation at any moment; but the President saw no occasion for preciptancy. On the other hand, he probably deemed it wise that the completion of this momentous executive act should be attended by every circumstance of deliberation.5

Signing of the historic document thus had to be postponed until after the usual open house at the White House on New Year’s Day. It was the first major White House social event since Willie Lincoln’s death ten months earlier. Mrs. Lincoln was attended by White House protocol official Benjamin French and told him, “O Mr. French, how much we have passed through since last we stood here.” French said she “seemed much affected through the first part of the reception and was too much overcome by her feelings to remain until it ended.”6

Journalist Noah Brooks wrote later that the President “received the diplomatic corps at eleven o’clock in the forenoon, and when these shining officials had duly congratulated him and had been bowed out, the officers of the Army and Navy who happened to be in town were received in the order of their rank. At twelve, noon, the gates of the White House grounds were flung wide open, and the sovereign people were admitted to the mansion in installments. I had gone to the house earlier, and now enjoyed the privilege of contrasting the decorous quiet of the receptions at the residences of lesser functionaries with the wild, tumultuous rush into the White House. Sometimes the pressure and the disorder were almost appalling; and it required no little engineering to steer the throng, after it had met and engaged the President, out of the great window from which a temporary bridge had been constructed for an exit.”7 Brooks also gave a more sardonic version of the White House reception in a newspaper report he filed at the time:

Secretary Welles and Postmaster General Blair did not receive their friends, on account of recent deaths in their families, Secretary Smith had handed in his resignation of the portfolio of the Department of the Interior, and had departed for the interior to assume his new duties as United States Judge for the district of Indiana; so he was also exempt. But the ‘Pres.,’ as he is familiarly termed by the unwashed, had not excuse, and at eleven he commenced his labors by receiving the Foreign Diplomats and their attaches. These dignitaries made a truly gorgeous appearance, arrayed in gold lace, feathers and other trappings, not to mention very good clothes. After they had paid their respects to the President and his wife, and had departed, the naval and military officers in town went in a shining body to wish the Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, ‘A happy New Year,’ which, we must suppose, was gratefully received by ‘Old Abe,’ with a sincere hope that it might be happier than his last two years have been. Precisely at 12 o’clock the great gates of the Executive Mansion were thrown open, and the crowd rushed in; our delegation from California, being vehicularly equipped, were obliged to fall into a line of coaches, and march up the drive at a truly funeral pace. The press was tremendous, and the jam most excessive; all persons, high or low, civil, uncivil, or otherwise, were obliged to fall into an immense line of surging, crowding sovereigns, who were all forcing their way along the stately portico of the White House to the main entrance. There was a detachment of police and a small detail of a Pennsylvania regiment on hand to preserve order; but, bless your soul! There was but precious little order in that crowd. Here was a Member of Congress [William Kellogg of Illinois] with a his coat tail half torn off, there a young lady in tears at the wreck of a ‘love of a bonnet’ with which she must enter the presence, as there is no retreat when one has once committed oneself to the resistless torrent of that mighty sea which surged against the doors of the White House and around the noble columns thereof. Anon, a shoulder strapped Brigadier, too late for the military entre, would enter the crowd with a manifest intention of going in directly; but he found his match in the sovereign crowd, which revenged its civil subordination by very uncivil hustling of the unfortunate officer. ‘If I could get my hand up, I would make you remember me,’ was the angry remark of a burly Michigander to a small Bostonian who had punched him in the victual basket. Bostonian knew that such a thing was impossible in that jam, and smiled his contempt. But the doors, closed for a few moments, open for a fresh dose of the ‘peops,’ and all, combatants and non combatants, changed their base about five feet, with the same brilliant results which McClellan announced of his Peninsular fight. The valves of the entrance close until the monster within has digested his new mouthful, and we fetch up this time against a fresh faced soldier, created in ‘this hour of our country’s peril,’ to mount guard at the White House, with a piece of deer skin, meant to typify a buck tail, on his cap. Says this military Cerberus: ‘My gosh!! Gentlemen, will you stan’ back? You can’t get in no faster by crowdin’. Oh, I say, will you stan’ back?’ To which adjuration the gay and festive crowd responded by flattening him against a pilaster, never letting him loose until his fresh country face was dark with an alarming symptom of suffocation, he the while holding his useless musket helplessly in air by his folded arms.

Inside, at last, we pour along the hall and enter a suite of rooms, straightening bonnets, coats and other gear, with a sigh of relief, for within the crowd are not. A single line, such as we see at the Post Office sometimes, reaches to the President, who is flanked on the left by Marshal [Ward Hill Lamon], who receives the name of each and gives it to the President as each advances to shake hands. Thus Lamon: ‘Mr Snifkins of California.’ To whom the President, his heavy eyes brightening, says ‘I am glad to see you, Mr. Snifkins you come from a noble State God bless her.’ Snifkins murmurs his thanks, is as warmly pressed by the hand as though the President had just begun his day’s work on the pump handle, and he is replaced by Mr. Biffkins, of New York, who is reminded by the Father of the Faithful that the Empire State has some noble men in the Army of the Union; and so we go on, leaving behind us the poor besieged and weary President, with his blessed old pump handle working steadily as we disappear into the famous East Room, a magnificent and richly furnished apartment, of which more some other time. A long window in an adjacent passage has been removed and a wooden bridge temporarily thrown across the sunken passage around the basement of the house, and by this egress the fortunate ones depart smiling in commiseration at the struggling unfortunates who are yet among the ‘outs.’ A primly dressed corps of cavalry officers, glorious in lace and jingling spurs, dash up to the portico and are disgusted to find that they must be swallowed up in the omnivorous crowd; but they must, for this is pre eminently the People’s Levee, and there is no distinction of persons or dress shown here.8

Washington’s pickpockets and police were also in attendance. The White House was located close to some of the city’s most disreputable neighborhoods and gambling houses. The disorder of White House levees offered a natural opportunity for the criminally-inclined. Visitors were lucky to leave with their own coats, much less their valuables. Journalist Brooks

Brooks observed the scene: “In the midst of this turmoil the good President stood serene and even smiling. But as I watched his face, I could see that he often looked over the heads of the multitudinous strangers who shook his hand with fervor and affection. “His eyes were with his thoughts, and they were far away on the bloody and snowy field of Fredericksburg, or with the defeated and worn Burnside, with whom he had that very day had a long and most depressing interview. In the intervals of his ceremonial duties he had written a letter to General Halleck which that officer construed as an intimation that his resignation of the office of general-in-chief would be acceptable to the President. It was not an occasion for cheer.”9

Nicolay and Hay wrote: “Vast as were its consequences, the act itself was only the simplest and briefest formality. It could in no wise be made sensational or dramatic. Those characteristics attached if at all, only to the long-past decisions and announcements of July 22 and September 22 of the previous year. Those dates had witnessed the mental conflict and the moral victory. No ceremony was made or attempted of this final official signing. The afternoon was well advanced when Mr. Lincoln went back from his New Year’s greetings, with his right hand so fatigued that it was an effort to hold the pen. There was no special convocation of the Cabinet or of prominent officials. Those who were in the house came to the executive office merely from the personal impulse of curiosity joined to momentary convenience. His signature was attached to one of the greatest and most beneficent military decrees of history in the presence of less than a dozen persons; after which it was carried to the Department of State to be attested by the great seal and deposited among the archives of the Government.”10

After the New Year’s levee downstairs in late morning and early afternoon, President Lincoln returned to his office where he signed the Emancipation Proclamation with a strong but slightly shaking hand. Mr. Lincoln observed: “Now this signature is one that will be closely examined. If they find my hand trembled they will say, ‘he had some compunctions.'”11 After he signed the document, “He looked up, smiled and said: ‘That will do.'”12 Before the official seal was affixed to the proclamation, Secretary of State William Seward also signed the Proclamation. Seward’s son Frederick preserved his recollections of the event:

At noon, accompanying my father, I carried the broad parchment in a large portfolio under my arm. We, threading our way through the throng in the vicinity of the White House, went upstairs to the President’s room, where Mr. Lincoln speedily joined us. The broad sheet was spread open before him on the Cabinet table. Mr. Lincoln dipped his pen in the ink, and then, holding it a moment above the sheet, seemed to hesitate. Looking around, he said:

“I never in my life felt more certain that I was doing right, than I do in signing this paper. But I have been receiving calls and shaking hands since nine o’clock this morning, till my arm is stiff and numb. Now this signature is one that will be closely examined, and if they find my hand trembled they will say ‘he had some compunctions.’ But anyway, it is going to be done.”

So saying, he slowly and carefully wrote his name at the bottom of the proclamation. The signature proved to be unusually clear, bold, and firm, even for him, and a laugh followed at his apprehension. My father, after appending his own name, and causing the great seal to be affixed, had the important document placed among the archives. Copies were at once given to the press.13

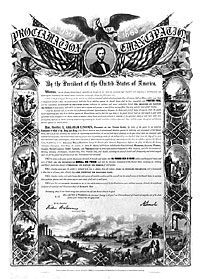

The proclamation began by repeating the text of the draft proclamation that had been issued 100 days earlier on September 22, 1862. It continued: “Now therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested, as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army, and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three.” After enumerating the areas under rebellion, the proclamation continued:

“And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order, and declare, that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward forever shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

“And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

“And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

“And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.”14

According to journalist Benjamin Perley Poore, “After having signed the famous Emancipation Proclamation on the 1st of January, 1863, Mr. Lincoln carefully put away the pen which he had used, for Mr. Sumner, who had promised it to his friend George Livermore, of Cambridge, the author of an interesting work on slavery. It was a steel pen with a wooden handle, the end of which had been gnawed by Mr. Lincoln – a habit that he had when composing anything that required thought.'”15

Across the hall in John Hay’s office, presidential aide William O. Stoddard was working. “Stod, the President wants you to make two copies of this right away. I must go back to him,” said John Hay, interrupting him. Stoddard later wrote: “I took the paper and some fresh sheets and went at it mechanically in the ordinary course of business. As I went on, however, from sentence to sentence, word to word, I wrote more slowly and with a queer tremor shaking my nerves. Then I looked up from my work and listened, for far away, nearer, nearer, I could hear the sound of clanking iron, as of breaking and falling chains, and after that the shouts of a great multitude, the laughter and songs of the newly free, and the anger of the fierce opposition, wrath, fury, dismay. For I was writing the first copies from Abraham Lincoln’s own draft of the January 1, 1863, Emancipation Proclamation.”16

It was a prosaic document. Historian Harold Holzer wrote: “The final Emancipation Proclamation, issued on January 1, 1863, did not add much to the vocabulary of freedom. Its first word was ‘where.’ ‘Thereof,’ ‘hereby,’ ‘hereafter,’ and ‘heretofore’ clutter the document. Space is devoted to a list of the states and counties exempted from the order. The most inspiring sentence – ‘I invoke the considerable judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God’ – was suggested by someone else. At least Lincoln did insert his belief that it was ‘sincerely believed to be an act of justice,’ hastily adding, ‘warranted by the Constitution, based upon military necessity.’ ‘Old Abe,’ an abolitionist critic complained, ‘seems utterly incapable of a really grand action.'”17

But the action was grand. Later that day Mr. Lincoln told Indiana Congressman Schuyler Colfax that three hours’ “hand-shaking is not calculated to improve a man’s chirography.” According to the President: “The South had fair warning, that if they did not return to their duty, I should strike at this pillar of their strength. The promise must now be kept, and I shall never recall one word.”18 That day, New York editor Thurlow Weed wrote: “The most ungenerous enemies of our cause will be compelled to respect this document, and to stand rebuked by its deep and solemn emphasis. It was must awaken responsive echoes in every land where liberty is loved and justice cherished.”19

The President was too busy that day to accompany his wife and Senator Orville Browning on a mid-afternoon carriage ride. Browning recorded in his diary that Mrs. Lincoln was still preoccupied with the death the previous February of her eleven-year-old son Willie and her attempts to communicate with him through the spirit world. While they rode to and from the Soldiers Home, where the Lincolns lived in the summer, Mrs. Lincoln talked to Browning about her latest seance. Browning wrote:

The President was engaged with Genl Burnside, and could not go. We drove to a house opposite the Post office for Mrs [Major] Wright of Chicago, and took her with us. On our way down there Mrs. Lincoln told her she had been, the night before, with old Isaac Newton, out to Georgetown, to see a Mrs Laury, a spiritualist and she had made wonderful revelations to her about her little son Willy who died last winter, and also about things on the earth. Among other things [the spiritualist] revealed that the cabinet were all enemies of the President, working for themselves, and that they would have to be dismissed, and others called to his aid before he had success.20

Back at the White House, President Lincoln had to meet again with Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, General Ambrose Burnside and General-in-Chief Henry W. Halleck. Burnside’s problems with the Army of the Potomac were so severe that he presented his resignation and suggested that Halleck and Stanton should too. Halleck was sufficiently insulted that he also wrote out his own resignation. Halleck had written Stanton: “Sir: From my recent interview with the President and yourself, and from the President’s letter of this morning, which you delivered to me at your reception. I am led to believe that there is a very important difference of opinion in regard to my relations toward general commanding armies in the field, and that I cannot perform the duties of my present office satisfactorily at the same time to the President and to myself. I therefore respectfully request that I may be relieved from further duties at General-in-Chief.” In order to placate General Halleck, President Lincoln withdrew the offending letter to Halleck. Mr. Lincoln’s frustration remained – as did that of General Burnside.

Later that day, Burnside put his ideas in writing: “Will you allow me, Mr. President, to say that it is of the utmost importance that you be surrounded and supported by men who have the confidence of the people and of the army, and who will at all times give you definite and honest opinions in relation to their separate departments, and at the same time give you positive and unswerving support in your public policy, taking at all times their full share of the responsibility for that policy? In no positions held by gentlemen near you are these conditions more requisite than those of the Secretary of War and General-in-Chief and the commanders of your armies. In the struggle now going on, in which the very existence of our Government is at stake, the interests of no one man are worth the value of a grain of sand, and no one should be allowed to stand in the way of accomplishing the greatest amount of public good.”21 In his letter, Burnside suggested that he as well as Secretary Stanton and General Halleck should resign. Mr. Lincoln did not accept Burnside’s resignation when it was presented the following day. “I deplore the want of concurrence with you, in opinion of your general officers, but I do not see a remedy,” wrote Mr. Lincoln as he struggled to keep the Union war effort together and promote the public good.

Not everyone was so upset with the events of January 1. Black abolitionist Frederick Douglass, who had previously been highly critical of President Lincoln, began to see a remedy to the problems of blacks in America. In his autobiography, Douglass wrote:

The first of January 1863 was a memorable day in the progress of American liberty and civilization. It was the turning point in the conflict between freedom and slavery. A death blow was then given to the slaveholding rebellion. Until then the federal arm had been more than tolerant to that relict of barbarism. It had defended it inside the slave states; it had countermanded the emancipation policy of John C. Fremont in Missouri; it had returned slaves to their so-called owners; and had threatened that any attempt on the part of the slaves to gain their freedom by insurrection, or otherwise, would be put down with an iron hand; it had even refused to allow the Hutchinson family to sing their antislavery songs in the camps of the Army of the Potomac; it had surrounded the houses of slaveholders with bayonets for their protection; and through it secretary of [state] William H. Seward, had given notice to the world that ‘however the war for the Union might terminate, no change would be made in the relation of master and slave.’22

Douglass wrote: “Upon this proslavery platform the war against the rebellion had been waged during more than two years. It had not been a war of conquest, but rather a war of conciliation. McClellan, in command of the army, had been trying, apparently, to put down the rebellion without hurting the rebels, certainly without hurting slavery, and the government had seemed to cooperate with him in both respects. Charles Sumner, William Lloyd Garrison, Wendell Phillips, Gerrit Smith, and the whole antislavery phalanx at the North had denounced this policy, and had besought Mr. Lincoln to adopt an opposite one, but in vain. Generals in the field and councils in the Cabinet had persisted in advancing this policy through defeats and disasters, even to the verge of ruin. We fought the rebellion, but not its cause. The key to the situation was the four million of slaves; yet the slave, who loved us, was hated, and the slaveholder, who hated us, was loved. We kissed the hand that smote us, and spurned the hand that helped us. When the means of victory were before us – within our grasp – we went in search of the means of defeat.”23

Douglass’s frustration and ill opinion of Mr. Lincoln were about to end. Douglass was in Boston on New Years’ Day 1863 and recalled the thrill when telegraphed news of the proclamation was received at an abolition rally at Tremont Temple. Although Douglass understood that the impact of the Proclamation was limited to areas under Confederate control, he also understood it was an important step toward complete emancipation of the country’s remaining slaves. Frederick Douglass later wrote in his memoirs:

And now, on this day of January 1, 1863, the formal and solemn announcement was made that thereafter the government would be found on the side of emancipation. This Proclamation changed everything. It gave a new direction to the councils of the Cabinet, and to the conduct of the national arms. I shall leave to the statesman, the philosopher, and historian, the more comprehensive discussion of this document, and only tell how it touched me, and those in like condition with me at the time.

I was in Boston, and its reception there may indicate the importance attached to it elsewhere. An immense assembly convened in Tremont Temple to await the first flash of the electric wires announcing the “new departure.” Two years of war prosecuted in the interests of slavery had made free speech possible in Boston, and we were now met together to receive and celebrate the first utterance of the long-hoped-for Proclamation, if it came, and if it did not come, to speak our minds freely; for in view of the past, it was by no means certain that it would come. The occasion, therefore, was one of both hope and fear. Our ship was on the open sea, tossed by a terrible storm; wave after wave was passing over us, and every hour was fraught with increasing peril. Whether we should survive or perish depended in large measure upon the coming of the Proclamation. At least so we felt. Although the conditions on which Mr. Lincoln had promised to withhold it had not been complied with, yet, from many considerations, there was room to doubt and fear. Mr. Lincoln was known to be a man of tender heart, and boundless patience; no man could tell to what length he might go, or might refrain from going in the direction of peace and reconciliation. Hitherto, he had not shown himself a man of heroic measures, and, properly enough, this step belonged to that class. It must be the end of all compromises with slavery– a declaration that thereafter the war was to be conducted on a new principle, with a new aim. It would be a full and fair assertion that the government would neither trifle, or be trifled with any longer. But would it come? On the side of doubt, it was said that Mr. Lincoln’s kindly nature might cause him to relent at the last moment that Mrs. Lincoln, coming from an old slaveholding family, would influence him to delay, and give the slaveholders one other chance.* (*I have reason to know that this supposition did Mrs. Lincoln great injustice.)

Every moment of waiting chilled our hopes, strengthened our fears. A line of messengers was established between the telegraph office and the platform of Tremont Temple, and the time was occupied with brief speeches from the Honorable Thomas Russell of Plymouth, Miss Anna E. Dickinson (a lady of marvelous eloquence), the Reverend Mr. Grimes, J. Sella Martin, William Wells Brown, and myself. But speaking or listening to speeches was not the thing for which the people had come together. The time for argument was passed. It was not logic, but the trump of jubilee, which everybody wanted to hear. We were waiting and listening as for a bolt from the sky, which should rend the fetters of four million of slaves; we were watching, as it were, by the dim light of the stars, for the dawn of a new day; we were longing for the answer to the agonizing prayers of centuries. Remembering those in bonds as bound with them, we wanted to join in the shout for freedom, and in the anthem of the redeemed.

Eight, nine, ten o’clock came and went, and still no word. A visible shadow seemed falling on the expecting throng, which the confident utterances of the speaks sought in vain to dispel. At last, when patience was well-nigh exhausted, and suspense was becoming agony, a man (I think was Judge Russell) with hasty step advanced through the crowd, and with a face fairly illumined with the news he bore, exclaimed in tones that thrilled all hearts, “It is coming!” “It is on the wires!” The effect of this announcement was startling beyond description, and the scene was wild and grand. Joy and gladness exhausted all forms of expression from shouts of praise, to sobs and tears. My old friend Rue, a colored preacher, a man of wonderful vocal power, expressed the heartfelt emotion of the hour, when he led all voices in the anthem, “Sound the Loud Timbrel O’er Egypt’s Dark Sea, Jehovah hath Triumphed, His People Are Free.” About twelve o’clock, seeing there was no disposition to retire from the hall, which must be vacated, my friend Grimes (of blessed memory), rose and moved that the meeting adjourn to the Twelfth Baptist Church, of which he was pastor, and soon that church was packed form doors to pulpit, and this meeting did not break up till near the dawn of day. It was one of the most affecting and thrilling occasions I ever witnessed, and a worthy celebration of the first step on the part of the nation at its departure from the thraldom of ages.

There was evidently no disposition on the part of this meeting to criticize the Proclamation; nor was there with anyone at first. At the moment we saw only its antislavery side. But further and more critical examination showed it to be extremely defective. It was not a proclamation of “liberty throughout all the land, unto all the inhabitants thereof,” such as we had hoped it would be; but was one marked by discrimination and reservations. Its operation was confined within certain geographical and military lines. It only abolished slavery where it did not exist, and left it intact where it did exist. It was a measure apparently inspired by the law motive of military necessity, and by so far as it was so, it would become inoperative and useless when military necessity should cease. there was much said in this line, and much that was narrow and erroneous. For my own part, I took the Proclamation, first and last, for a little more than it purported; and saw in its spirit a life and power far beyond its letter. Its meaning to me was the entire abolition of slavery, wherever the evil could be reached by the federal arm, and I saw that its moral power would extend much further. It was in my estimation an immense gain to have the war for the Union committed to the extinction of slavery, even from a military necessity. It is not a bad thing to have individuals or nations do right though they do so from selfish motives. I approved the one-spur-wisdom of “Paddy,” who thought if he could get one side of his horse to go, he could trust the speed of the other side.

The effect of the Proclamation abroad was highly beneficial to the loyal cause. Disinterested parties could now see in it a benevolent character. It was no longer a mere strife for territory and dominion, but a contest of civilization against barbarism.

The proclamation itself was like Mr. Lincoln throughout. It was framed with a view to the least harm and the most good possible in the circumstances, and with especial consideration of the latter. It was thoughtful, cautious and well guarded at all points. While he hated slavery, and really desired its destruction, he always proceeded against it in a manner the least likely to shock or drive from him any who were truly in sympathy with the preservation of the Union, but who were not friendly to emancipation. For this he kept up the distinction between loyal and disloyal slaveholders, and discriminated in favor of the one, as against the other. In a word, in all that he did, or attempted, he made it manifest that the one great and all commanding object with him was the peace and preservation of the Union. His wisdom and moderation at this point were for a season useful to the loyal cause in the border states, but it may be fairly questioned whether it did not chill the Union ardor of the loyal people of the North in some degree, and diminish rather than increase the sum of our power against the rebellion: for moderate cautions and guarded as was this Proclamation, it created a howl of indignation and wrath amongst the rebels and their allies. the old cry was raised by the copperhead organs of “an abolition war,” and a pretext was thus found for an excuse for refusing to enlist, and for marshalling all the Negro prejudice of the North on the rebel side. Men could say they were willing to fight for the Union, but that they were not willing to flight for the freedom of the Negroes; and thus it was made difficult to procure enlistments or to enforce the draft.24

The black abolitionist leader was euphoric: “Border State influence, and the influence of half-loyal men, have been exerted and have done their worst. The end of these two influences is implied in this proclamation….’Free forever’ oh! Long enslaved millions, whose cries have so vexed the air and sky, suffer on a few more days in sorrow, the hour of your deliverance draws nigh! Oh! Ye millions of free and loyal men who have earnestly sought to free your bleeding country from the dreadful ravages of revolution and anarchy, lift up now your voices with joy and thanksgiving for with freedom to the slave will come peace and safety to your country.”25 Eliza S. Quincy, the wife of Josiah Quincy, wrote Mrs. Lincoln:

I enclose the Programme of the celebration of the President’s Proclamation at the Boston Music Hall, – yesterday, – with M. S. notes of the incidents which occurred, during the performance.-

In full confidence of the steadiness of the President’s purpose, – the arrangements were all made several weeks ago.– But it was not until the vast audience had assembled and the performances had commenced that the news arrived that the Proclamation was actually on the wires of the telegraph.–

The reception of this intelligence was worthy of “the Declaration of Emancipation”,! – which must rank in future with that of Independence, – & the 1st of January 1863, – with the 4th of July 1776.-

It was a sublime moment, – the thought of the millions upon millions of human beings whose happiness was to be affected & freedom secured by the words of President Lincoln, was almost overwhelming.

To us also the remembrance of many friends who had worked & labored in this cause, for many years, but who had departed without the accomplishing of those hopes, which we had lived to witness was very affecting.

It was a day & an occasion never to be forgotten.– I wish you & the President could have enjoyed it with us, here.-26

Harold Holzer wrote in Lincoln: Seen and Unseen that President Lincoln’s handling of the proclamation was curiously understated: “Unaware of the power of image-making, Lincoln made the proclamation official in his private office, before just a few witnesses. He made no speech that day, met no delegation of African Americans, visited no slave family, saw no abolitionists, presided over no ceremony.”27 According to Holzer, “To understand Lincoln’s stubborn hesitation, and his subsequent use of confusing public statements and rigidly stilted prose, one must consider the hotly charged race issue in terms of his time, not ours – an age of rampant racism in which only a small percentage of white America supported emancipation and but a fraction of that minority would have tolerated, much less supported, the then-radical notion of racial equality.”28

Historian John Hope Franklin wrote: “Young Edward Rosewater, scarcely 20 years old, had an exciting New Year’s Day. He was a mere telegraph operator in the War Department, but he knew the President and had gone to the White House reception earlier that day and had greeted him. When the President made his regular call at the telegraph office that evening, young Rosewater was on duty and was more excited than ever. He greeted the President and went back to his work. Lincoln walked over to see what Rosewater was sending out. It was the Emancipation Proclamation! If Rosewater was excited, the President seemed the picture of relaxation. After watching the young operator for a while, the President went over to the desk of Tom Eckert, the chief telegraph operator in the War Department, sat in his favorite chair, where he had written most of the Preliminary Proclamation the previous summer, and gave his feet the proper elevation. For him, it was the end of a long, busy, but perfect day.”29

“After the Washington Evening Star published a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation on the afternoon of January 1, a parade of whites and blacks marched past the White House, cheering Lincoln. At one point the president appeared at an upstairs window, but he refused to meet his admirers,” wrote Lincoln chronicler William K. Klingaman. “Elsewhere in the city, a group of Negroes in front of the office of the Reverend D.B. Nichols, superintendent of the city’s contraband department’ on Twelfth and O Streets. They sang spirituals, including ‘God Down Moses’ and ‘I’m a Free Man Now, Jesus Christ Made Me Free.’ A preacher who called himself John de Baptis’ reminded the audience of ‘how it was in Dixie;, when you worked all day without giving satisfaction. I have worked by the month for six months since I left Dixie, and the money is all my own; and I’ll soon eddicate [sic] my children. But brethren,’ he went on, don’t be too free. The lazy man can’t go to Heaven….You must depend upon yourself and be honest.'”30 Historian Margaret Leech wrote:

In the city, the Negroes who had been emancipated the preceding April, and the vastly larger group of freedmen received the news without disorderly excitement and with few outbursts of rejoicing. It was a great day for their race. But the intelligent among them were skeptical and disillusioned. The white man’s oppression had taught them that freedom might be an empty privilege. That spring, the Reverend James Reed arose in the Fifteenth Street Presbyterian Church to say that he had purchased his liberty years before, but could not say that he had ever felt himself free.

Above all, it was fear that kept the Washington Negroes quiet. Since the emancipation in the District, there had been demonstrations of hostility to them. The Washington guttersnipes had been ready with insults and even with stones. The President’s proclamation increased the antagonism of the white rowdies. Apprehensively, uneasy over rumors of a projected disturbance, the colored people gathered in January at the Israel Church near the Capitol, to make plans for a mass meeting in recognition of the proclamation. Stones thumped against the sides of the building. Panic spread, as panes of glass were shattered. The women, clutching shawls and cloaks and furs, hurried to the door. Some of the men huddled close to the wall between the windows. Others stood defiantly brandishing their canes. Even after the arrival of the police, some time passed before order was restored. The Star reporter was of the opinion that they would have defended themselves desperately. The proposed mass meeting was not held.31

Elsewhere in Washington, the emotions ran higher. The Reverend Henry M. Turner was a leader in the Washington community and minister of the Israel Bethel Church. On January 1, Reverend Turner led an impromptu celebration of emancipation among his black congregants: “Seeing such a multitude of people in and around my church, I hurriedly went up to the office of the first paper in which the proclamation of freedom could be printed, known as the ‘Evening Star,’ and squeezed myself through the dense crowd that was waiting for the paper. The first sheet run off with the proclamation in it was grabbed for by three of us, but some active young man got possession of it and fled. The next sheet was grabbed for by several, and was torn into tatters. The third sheet from the press was grabbed for by several, but I succeeded in procuring so much of it as contained the proclamation, and off I went for life and death. Down Pennsylvania Avenue I ran as for my life, and when the people saw me coming with the paper in my hand they raised a shouting cheer that was almost deafening. As many as could get around me lifted me to a great platform, and I started to read the proclamation. I had run the best end of a mile, I was out of breath, and could not read. Mr. Hinton, to whom I handed the paper, read it with great force and clearness. While he was reading every kind of demonstration and gesticulation was going one. Men squealed, women fainted, dogs barked, white and colored people shook hands, songs were sung, and by this time cannons began to fire at the navy-yard, and follow in the wake of the roar that had for some time been going on behind the White House…Great processions of colored and white men marched to and fro and passed in front of the White House and congratulated President Lincoln on his proclamation. The President came to the window and made responsive bows, and thousands told him, if he would come out of that palace, they would hug him to death…It was indeed a time of times, and a half time, nothing like it will ever be seen again in this life.32

Teacher Charlotte Forten reported the reaction at Camp Saxton in South Carolina, where the First South Carolina Volunteers of black soldiers was based. “There were the black soldiers in their blue coats and scarlet pantaloons, the officers of this and other regiments in their handsome uniforms, and crowds of lookers-on, – men, women, and children, of every complexion, grouped in various attitudes under the moss-hung trees. The faces of all wore a happy, interested look. The exercises commenced with a prayer by the chaplain of the regiment.” Forten wrote that a reading of the Emancipation was “enthusiastically cheered. Rev. Mr. French presented to the Colonel [Thomas W. Higginson] two very elegant flags, a gift to the regiment from the Church of the Puritans, accompanying them by an appropriate and enthusiastic speech. At its conclusion, before Colonel Higginson could reply, and while he still stood holding the flags in his hand, some of the colored people, of their own accord, commenced singing, ‘My Country, ’tis of thee.’ It was a touching and beautiful incident, and sent a thrill through all our hearts. The Colonel was deeply moved by it. He said that that reply was far more effective than any speech he could make.”33

In New York City, attorney George Templeton Strong observed in his diary that it was to “be remembered, with gratitude to the Author of all Good, that on January 1st the Emancipation Proclamation was duly issued. The nation may be sick unto speedy death and past help from this and any other remedy, but if it is, its last great act is one of repentance and restitution….”34 A Brooklyn family wrote Mr. Lincoln: “Language has no words to express how much we thank you for your glorious Proclamation. You have added glory to the sky & splendor to the sun, & there are but few men who have ever done that before, either by words or acts. We enthusiastically ‘went in’ for you at the last Presidential campaign, but pardon us if we candidly tell you that on the day when your Proclamation was issued, we said for the first time since your Administration, from the bottom of our hearts, ‘God bless Abraham Lincoln’!”35

Historian Edna Greene Medford wrote: “The more one recognizes the centrality of enslaved and free people of color in the process of emancipation, however, the more one becomes aware of the significance of Lincoln and his historic document to the people who were most directly affected by its provisions. Despite its shortcomings (and there were many), contemporary African Americans saw in the Emancipation Proclamation a document with limitless possibilities. To them, it represented the promise not only of freedom and an end to their degradation, but it encouraged the hope for full citizenship and inclusion in the country of their birth as well. Although liberating in theory rather than in reality, people of color saw the proclamation as a watershed in their quest for human dignity and recognition as Americans.”36

Confederate President Jefferson Davis responded to the proclamation by telling the Confederate Congress: “We may well leave it to the instincts of that common humanity which a beneficent creator has implanted in the breasts of our fellow men of all countries to pass judgment on a measure by which several millions of human beings of an inferior race – peaceful and contented laborers in their sphere – are doomed to extermination, while at the same time they are encouraged to a general assassination of their masters by the insiduous [sic] recommendation to abstain from violence unless in necessary defence. Our own destestation of those who have attempted the most execrable measures recorded in the history of guilty man is tempered by profound contempt for the impotent rage which it discloses. So far as regards the action of this government on such criminals as may attempt its execution, I confine myself to informing you that I shall – unless in your wisdom you deem some other course expedient – deliver to the several State authorities all commissioned officers of the United States that may hereafter be captured by our forces in any of the States embraced in the Proclamation, that they may be dealt with in accordance with the laws of those States providing for the punishment of criminals engaged in exciting servile insurrection. The enlisted soldiers I shall continue to treat as unwilling instruments in the commission of these crimes, and shall direct their discharge and return to their homes on the proper and usual parole.”37

On January 25, President Lincoln spoke to an abolitionist delegation and admitted that he had “not expected much from it at first and consequently had not been disappointed. He had hoped, and still hoped, that something would come of it after a while.” He added that he was “convinced that his administration would not have been supported by the country at any earlier stage of the war in a policy of emancipation.” Nevertheless, said the President, “I believe the Proclamation has knocked the bottom out of slavery, though at no time have I expected any sudden results from it.”38 Historian Kenneth M. Stampp wrote: “Even so, the Proclamation, which also authorized the recruitment of blacks for the Union army, did less than justice to an act potentially so momentous in its social consequences. Apart from political expediency, the reason, in all probability, was that when Lincoln issued it himself did not fully recognize that the conflict thereby would be transformed into a great social revolution. In his view, it was still a war for the Union, nothing more. ‘For this alone have I felt authorized to struggle,’ he assured a critic, ‘and I seek neither more nor less now.'”39

Footnotes

- John Hope Franklin, The Emancipation Proclamation, p. 88.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 31 (Letter to Henry W. Halleck, January 1, 1863).

- Benjamin Perley Poore, Perley’s Reminiscences, Volume II, p. 137.

- Allen C. Guelzo, Abraham Lincoln: Redeemer President, p. 345.

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VI, p. 421-430.

- Ruth Painter Randall, Mary Lincoln: Biography of a Marriage, p. 286.

- Noah Brooks, Washington in Lincoln’s Time, p. 48.

- Michael Burlingame, editor, Lincoln Observed: Civil War Dispatches of Noah Brooks, p. 15-17 (January 3, 1863).

- Noah Brooks, Washington in Lincoln’s Time, p. 48-49.

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VI, p. 421-430.

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, p. 87.

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months at the White House, p. 270.

- Frederick Seward, Reminiscences of a War-time Statesman and Diplomat, p. 227.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 28-30.

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 230 (Benjamin Perley Poore).

- William O. Stoddard, Jr., editor, Lincoln’s Third Secretary, p. 169-170.

- Harold Holzer, Lincoln Seen and Heard, p. 188.

- Francis B. Carpenter, Six Months in the White House, p. 87.

- Thurlow Weed Barnes, editor, The Life of Thurlow Weed, p. 430.

- Theodore Calvin Pease, editor, Orville Hickman Browning, Diary of Orville Hickman Browning, Volume I, p. 608-609 (January 1, 1863).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VI, p. 31 (Letter to Henry W. Halleck, January 1, 1863).

- Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass,p. 426.

- Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, p.254 .

- Frederick Douglass, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, p. 342-346.

- James M. McPherson, The Negro’s Civil War, p. 94.

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter From Eliza S. Quincy to Mary Todd Lincoln, January 2, 1863).

- Harold Holzer, Lincoln Seen and Heard, .

- Harold Holzer, Lincoln Seen and Heard, .

- John Hope Franklin, The Emancipation Proclamation, , .

- William K. Klingaman, Abraham Lincoln and the Road to Emancipation, 1861-1865, p. 233.

- Margaret Leech, Reveille in Washington, p. 250.

- James M. McPherson, Marching Toward Freedom, p. 21.

- James M. McPherson, The Negro’s Civil War, p. 63-64.

- Allan Nevins, editor, Diary of the Civil War, 1860-1865: George Templeton Strong, p. 286 (January 3, 1863).

- Abraham Lincoln Papers at the Library of Congress. Transcribed and Annotated by the Lincoln Studies Center, Knox College. Galesburg, Illinois. (Letter from Gertrude Bloede, Katie Bloede, and Victor G. Bloede to Abraham Lincoln, January 4, 1863).

- Martin H. Greenberg and Charles G. Waugh, editor, The Price of Freedom: Slavery and the Civil War, Volume I, p. 5-6Edna Greene Medford, “Beckoning Them to the Dreamed of Promise of Freedom: African Americans and Lincoln’s Proclamation of Emancipation.

- Joseph T. Wilson, The Black Phalanx: African American Soldiers in the War of Independence, the War of 1812 & the Civil War, p. 316-317.

- Don E. and Virginia E. Fehrenbacher, editor, Recollected Words of Abraham Lincoln, p. 120.

- Gabor S. Boritt, editor, Lincoln the War President, p. 138-140 (Kenneth M. Stampp, “The United States and National Self-determination”).