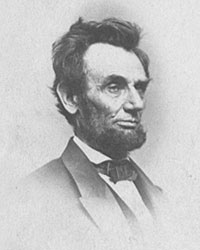

With emancipation in effect and black soldiers serving in the military, the next major confrontation between President Lincoln and Radical Republicans in Congress came in 1864 over reconstruction. Historian Benjamin Thomas wrote: “Under Lincoln’s careful nurture Louisiana and Arkansas had already organized provisional governments, and with Tennessee taking steps to the same end, the apprehensive radicals decided that they must take counteraction. Sardonic Ben Wade headed the resistance to Lincoln’s reconstruction efforts in the Senate, while vehement, ambitious Henry Winter Davis, a cousin of Lincoln’s friend David Davis and an implacable rival of Montgomery Blair in Maryland politics, emerged as the House spokesman for the radicals. Abetted by [Zachariah] Chandler and [Charles] Sumner in the Senate, and by [Thaddeus] Stevens and abolitionist George W. Julian in the House, these men became the sponsors of a bill sharply at odds with Lincoln’s lenient plan of reconstruction.”1

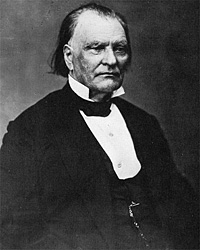

Historian T. Harry Williams wrote: “The Jacobin bosses were grimly confident that they could whip Lincoln on the reconstruction issue. They believed that public opinion had moved up to their position and that the people would support a program which included the suffrage for the Southern Negroes as one of its cardinal principles. They chose to precipitate the inevitable struggle with the president; their object was to defeat congressional recognition of Lincoln’s ten per cent governments. Early in February the radicals prepared to jam through Congress a resolution declaring that the eleven seceded states were not entitled to representation in the electoral college. This struck directly at Lincoln’s four reconstruction states. Wade, who led the debate for the Jacobins, bitterly denounced Lincoln’s reconstruction plan as ‘the most absurd and impracticable that ever haunted the imagination of a statesman.”2

President Lincoln’s climatic confrontation with Congress over Reconstruction came in July 4, 1864. The Senate had finally approved a Reconstruction bill sponsored by Senator Benjamin F. Wade and Congressman Henry Winter Davis. According to historian Hans Trefousse: “Wade had scored a triumph. By cleverly tempering his radicalism with practicality, he had skillfully maneuvered his bill through the Senate. Thus he himself had suggested that the amendment for Negro suffrage be discarded. Rather than defeat the measure altogether, he had even voted for it as amended by Senator Brown, much as he had opposed the change in the Committee of the Whole. Moreover, the bill itself was relatively mild, especially when compared with the measures which were to follow later. Although it contained a number of harsh exclusion clauses to keep down Democratic majorities in the South, it nevertheless offered a speedy and relatively painless way for Southern states to re-enter the Union. The bill was clearly framed by men who expected not merely to pass it in Congress but also to obtain the President’s signature for it.”3

The Wade-Davis Bill contained three Reconstruction demands, according to historian Allan Nevins: “One, a requirement that the new constitutions cancel all debts incurred in aid of the rebellion, was perfectably equitable. It would impoverish some Southerners, but they deserved their losses. Quite different was a Draconian stipulation that the constitutions should forbid all men who held high civil office under the Confederacy, or military rank above a colonelcy, to vote for a legislator or governor, or occupy these positions. No former office-holder or person who had voluntarily borne arms against the United States could take the oath, and no one who did not take the oath could vote for the constitutional convention. This would proscribe the ablest and most experienced leaders in the South. Worse still, in theory and practise, was a demand that the constitution abolish slavery. This was plainly unconstitutional, for Congress had no power to deal with slavery inside the States. It was also unwise, for if slavery were thus abolished by national action, the nation might be expected to take steps to aid and protect the freedmen for which it had made no preparatory study, and possessed no adequate machinery. The Wade-Davis bill provided that, whenever a State constitution embodying these iron provisions had been adopted by a majority of the registered voters, the President, with prior Congressional assent, should recognize the government so established as competent to send men to Congress and choose Presidential electors.”4

In his drive for passage of his bill Wade was willing to drop a provision which would have opened voting rights to blacks. “In my anxiety to give these people all their rights,” Wade told the Senate, “I feel now that this bill is of great importance, and that this amendment, if adopted, will probably jeopardize the bill; and, as I believe that the provisions of this bill outweigh all such considerations, and at this state of the proceedings that there is no time for discussion upon it, although I agreed to this amendment in committee, I would rather it should not be adopted, because, in my opinion, it will sacrifice the bill.”5

There were other problems, especially with the status of seceded states and the authority of Congress. “A considerable number of Republicans were unwilling to deal prematurely with reconstruction, and B. Gratz Brown of Missouri offered a substitute which proposed that Congress simply declare its intention not to count the presidential votes of any seceded states. Future Congresses might then cope with reconstruction in their in their own way,” wrote Wade biographer Hans L. Trefousse. Wade “conceded that gentlemen might differ on the subject of the seceded states’ relationship to the general government, but he was sure that Congress had exclusive jurisdiction.”

Wade made it clear that they were engaged in a constitutional power struggle with the White House. “The Executive ought not to be permitted to handle this great question to his own liking,” said Senator Wade in urging the bill’s passage. “It does not belong, under the Constitution to the President to prescribe the rule. It belongs to us. The President undertook to fix a rule upon which he would admit these States back into the Union. It was not upon any principle of republicanism, because he prescribed the rule to be that when one tenth of the population would take a certain oath, they might come in as States. When we consider that in the light of American principle, to say the least of it was absurd….Until majorities can be found loyal and trustworthy for State government, they must be governed by a stronger hand.”

Historian Bruce Tap wrote: “There was intense congressional pressure on the president to accept the [Wade-Davis] bill. Illinois Republican congressman Jesse O. Norton warned Lincoln that failure to sign might be politically damaging. On July 4 Zachariah Chandler visited the White House to discuss the matter. When Lincoln chided Congress for placing such an important matter before him with only a few days for consideration, Chandler asserted that the main issue was abolishing slavery ‘in the reconstructed states.’ ‘I doubt that Congress can legally do that,’ the president countered. ‘It is no more than you have done yourself.'”6

Biographers Nicolay and Hay wrote: “The scene, as the President thus squarely confronted the Radicals who intended to destroy his Reconstruction program, was one of the most dramatic in wartime history. The House had occupied its last minutes with a reading of the Declaration of Independence. Sitting in the President’s room in the Capitol, Lincoln had been signing final bills. Sumner entered with characteristic vehemence, his fanatic mind centered on the measure. George S. Boutwell, equally nervous and angry, raised a voice of lamentation. Zach Chandler made a scene by buttonholing the President, threatening him with the prospect that the loss of the Wade-Davis Bill would cost the Republicans Ohio and Michigan in the fall election, and denouncing his constitutional objections. Secretary [William P.] Fessenden reminded the excited group that Republicans had always agreed that Congress had no power over slavery inside the States.”7 Presidential aide John Hay recorded the scene:

Today Congress adjourned at noon. I was in the House for a few minutes before the close. They read the declaration of Independence there in spite of the protest of Sunset Cox that it was an insurrectionary document & would give aid & comfort to the rebellion.

In the Presidents room we were pretty busy signing & reporting bills. Sumner was in a state of intense anxiety about the Reconstruction Bill of Winter Davis. Boutwell also expressed his fear that it would be pocketed. Chandler came in and asked if it was signed ‘No.’ He said would make a terrible record for us to fight if it were vetoed: the President talked to him a moment. He said, ‘Mr Chandler, this bill was placed before me a few minutes before Congress adjourns. It is a matter of too much importance to be swallowed in that way.’ ‘If it is vetoed it will damage us fearfully in the North West. It may not in Illinois; it will in Michigan and Ohio. The important point is that one prohibiting slavery in the reconstructed States.’

Prest. ‘That is the point on which I doubt the authority of Congress to act.”

Chandler. ‘It is no more than you have done yourself.’

President. ‘I conceive that I may in an emergency do things on military grounds which cannot be done constitutionally by Congress.’

Chandler. ‘Mr President I cannot controvert yr position by argument, I can only say I deeply regret it.’

Exit Chandler.

The President continued, ‘I do not see how any of us now can deny and contradict all we have always said, that congress has no constitutional power over slavery in the states.’ Mr Fessenden, who had just come into the room, said, ‘I agree with you there, Sir. I even had my doubts as to the constitutional efficacy of your own decree of emancipation, in such cases where it has not been carried into effect by the actual advance of the Army.’

Prest. ‘This bill and this position of these gentlemen seems to me to make the fatal admission (in asserting that the insurrectionary States are no longer in the Union) that States whenever they please may of their own motion dissolve their connection with the Union. Now we cannot survive that admission, I am convinced. If that be true, I am not President, these gentlemen are not Congress. I have laboriously endeavored to avoid that question ever since it first began to be mooted & thus to avoid confusion and disturbance in our own counsels. It was to obviate this question that I earnestly favored the movement for an amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery, which passed the Senate and failed in the House. I thought it much better, if it were possible, to restore the Union without the necessity of a violent quarrel among its friends, as to whether certain States have been in or out of the Union during the war: a merely metaphysical question and one unnecessary to be forced into discussion.’

Seward, Usher and Fessenden seemed entirely in accord with this.

After we left the Capitol I said I did not think Chandler, man of the people and personally popular as he was, had any definite comprehension of popular currents and influence – that he was out of the way now especially – that I did not think people would bolt their ticket on a question of metaphysics.

The Prest answered, ‘If they choose to make a point upon this I do not doubt that they can do harm. They have never been friendly to me & I don’t know that this will make any special difference as to that. At all events, I must keep some consciousness of being somewhere near right: I must keep some standard of principle fixed within myself.’8

According to historian T. Harry Williams, “The information reached the House as the members were rushing out after the adjournment. Henry Winter Davis, overcome by a paroxysm of fury, stood by his desk waving his arms wildly, denouncing the president in a speech to an empty wall.”9 According to Henry Winter Davis’s biographer Gerald S. Henig, “For the most part, Davis’s Republican colleagues in the House and Senate shared a similar attitude. Sumner reported to Chase that there was ‘intense indignation’ against Lincoln on account of his pocketing the bill. And James G. Blaine later commented that the President’s course ‘met with almost unanimous dissent on the part of Republican members of Congress, and violent opposition from the more radical members of both Houses. If Congress had been in session at the time a very rancorous hostility would have developed against the President.'”10

Historian Allan Nevins wrote that the Radical Republicans were challenging President Lincoln: “We may well believe the assertion of contemporaries that Henry Winter Davis was beside himself with rage that afternoon, for his boiling-point was low. But we must reject both the statement of young James G. Blaine that Republican members of Congress almost unanimously dissented from Lincoln, and Sumner’s preposterous assertion that Lincoln later expressed regret that he had not signed the Wade-Davis Bill.”11

Pennsylvania Congressman Thad Stevens denounced the pocket veto: “What an infamous proclamation! The Prest. is determined to have the electoral votes of the seceded States at least of Tenn. Ark. Lou & Flor. Perhaps also of S. Car. The idea of pocketing a bill and then issuing a proclamation as to how far he will conform to it, is matched only by signing a bill and then sending in a veto [[which was more or less what Lincoln had done with the second confiscation act] – How little of the rights of war and the law of nations our Prest. knows! But what are we to do? Condemn privately and applaud publicly! – The Conscription Act weighs heavily on our people’s judgt. as expected.”12

Two days later, Salmon P. Chase, whose own confrontations with President Lincoln had led to his resignation only days earlier, recorded in his diary: “Senator [Samuel] Pomeroy came to breakfast – he says there is great dissatisfaction with Mr. Lincoln, which has been much exasperated by the pocketing of the reorganization bill. [James] Garfield said yesterday that when the news of the intention of the President to pocket this bill came to the House on Monday, [Jesse] Norton of Ills the special friend of the Presidents said it was impossible [?] and would be fatal. G—– told him, if he desired to prevent it he should go to him at his room in the Capitol at once and remonstrate. Norton started, almost running; but returned after a little. ‘Did you see him.’ ‘Yes’ ‘Will he sign.’ ‘No – great mistake but no use trying to prevent it.’ Pomeroy says he means to go on a Buffalo hunt and then to Europe. He cannot support Lincoln, but wont desert his principles. I myself [am] of the same sentiments; though not willing now to decide what duty may demand next fall.”13

On July 8, President Lincoln issued an official proclamation concerning reconstruction – further infuriating his congressional opponents. The President wrote:

Whereas, at the late Session, Congress passed a Bill, ‘To guarantee to certain States, whose governments have been usurped or overthrown, a republican form of Government,’ a copy of which is hereunto annexed:

And whereas, the said Bill was presented to the President of the United States, for his approval, less than one hour before the sine dieadjournment of said Session, and was not signed by him:

And whereas, the said Bill contains, among other things, a plan for restoring the States in rebellion to their proper practical relation to the Union, which plan expresses the sense of Congress upon that subject, and which plan it is now thought fit to lay before the people for their consideration.

Now, therefore, I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, do proclaim, declare, and make known that, while I am, (as I was in December last, when by proclamation I propounded a plan for restoration) unprepared, by a formal approval of this Bill, to be inflexibly committed to any single plan of restoration; and, while I am also unprepared to declare, that the free-state constitutions and governments, already adopted and installed in Arkansas and Louisiana, shall be set aside and held for nought, thereby repelling and discouraging the loyal citizens who have set up the same, as to further effort; or to declare a constitutional competency in Congress to abolish slavery in States, but am at the same time sincerely hoping and expecting that a constitutional amendment, abolishing slavery through the nation, may be adopted, nevertheless, I am fully satisfied with the system for restoration contained in the Bill, as one very proper plan for the loyal people of any State choosing to adopt it; and that I am, and at all times shall be, prepared to give the Executive aid and assistance to any such people, so soon as the military resistence to the United States shall have been suppressed in any such State, and the people thereof shall have sufficiently returned to their obedience to the Constitution and the law of the United States,– in which cases, military Governors will be appointed, with directions to proceed according to the Bill.14

Henry Wade Davis biographer Gerald S. Henig wrote: ‘Already incensed by the President’s pocket veto, Davis was even more outraged by the Proclamation. Together with his associates, he regarded the document as an affront. Thaddeus Stevens was particularly upset.”15 Eight months later, Wade denounced the proclamation as “the most contentious, the most anarchical, the most dangerous proposition that was ever put forth for the government of a free people.”16 Historian Hans L. Trefousse wrote: “To Wade, the veto of his measure was a severe blow. To have gone so far, to have coaxed, wheedled, and pushed the bill through the Senate only to have it pocketed by the President – this was a disappointment which could drive a man to extremes…That he had called the measure ‘one very proper plan for the people of any State choosing to accept it,’ that he had merely proclaimed his opposition to any fixed scheme, that he had called for a constitutional amendment to abolish slavery, that he had asserted that he had not signed the bill lest he discourage Unionists already committed to his own plan – these considerations did not mollify Wade. Together with his associates, he considered the President’s action an affront.”17

The wounds left by the Wade-Davis controversy were not easily healed. Nearly seven months later, Senator Wade called President Lincoln’s post-veto proclamation “the most contentious, the most anarchial, the most dangerous proposition that was ever put forth for the government of a free people.”18Wade and Congressman Davis immediately planned a counterattack. “Because Congress had no official way to respond to this quasi-veto message, Wade and Davis decide to publish their own statement in the press. As they drafted it, their pent-up bitterness toward ‘Executive usurpation’ carried them into rhetorical excess,” wrote historian James M. McPherson.19 The message concluded that President Lincoln should “confine himself to his Executive duties – to obey and execute, not make the laws – to suppress by arms armed rebellion, and leave political reorganization to Congress.” The manifesto began: “The proclamation is neither an approval nor a veto of the bill; it is therefore a document unknown to the laws and Constitution of the United States. So far as it contains an apology for not signing the bill, it is a political manifesto against the friends of the government. So far as it proposes to execute the bill, which is not a law, it is a grave executive usurpation….”20 The Wade-Davis Manifesto, which was printed in the New York Tribune on August 5, 1864, read:

The President, by preventing this bill from becoming a law, holds the electoral votes of the rebel States at the dictation of his personal ambition. If those votes turn the balance in his favor, is it to be supposed that his competitor, defeated by such means, will acquiesce? If the rebel majority assert their supremacy in those States, and send votes which elect an enemy of the government, will we not repel his claims? And is not that civil war for the presidency inaugurated by the votes of rebel States? Seriously impressed with these dangers, Congress, ‘the proper constitutional authority,’ formally declared that there are no State governments in the rebel States, and provided for their erection at a proper time; and both the Senate and House of Representatives rejected the Senators and Republicans chosen under the authority of what the President calls the free constitution and government of Arkansas. The President’s proclamation ‘holds for naught’ this judgment, and discards the authority of the Supreme Court and strides headlong toward the anarchy his proclamation of the 8th of December inaugurated. If electors for President be allowed to be chosen in either of those States, a sinister light will be cast on the motives which induced the President to ‘hold for naught’ the will of Congress rather than his governments in Louisiana and Arkansas. That judgment of Congress which the President defies was the exercise of an authority exclusively vested in Congress by the constitution to determine what highest of judicial authority binding on all other departments of the government….A more studied outrage on the legislative authority of the people has never been perpetrated. Congress passed a bill; the President refused to approve it, and then by proclamation puts as much of it in force as he sees fit, and proposes to execute those parts by officers unknown to the laws of the United States and not subject to the confirmation of the Senate! The bill directed the appointment of provisional governors by and with the advice and consent of the Senate. The President, after defeating such a law, proposes to appoint without law, and without the advice and consent of the Senate, military governors for the rebel States! He has already exercised this dictatorial usurpation in Louisiana, and he defeated the bill to prevent its limitation….

The President has greatly presumed on the forbearance which the supporters of his administration have so long practiced, in view of the arduous conflict in which we are engaged, and the reckless ferocity of our political opponents. But he must understand that our support is of a cause and not of a man; that the authority of Congress is paramount and must be respected; and that the whole body of the Union men of Congress will not submit to be impeached by him of rash and unconstitutional legislation; and if he wishes our support, he must confine himself to his executive duties – to obey and execute, not makes the laws – to suppress by arms armed rebellion, and leave political reorganization to Congress.

If the supporters of the government fail to insist on this, they become responsible for the usurpations which they fail to rebuke, and are justly liable to the indignation of the people, whose rights and security, committed to their keeping, they sacrifice. Let them consider the remedy for these usurpations, and, having found it, fearlessly execute it!21

These congressmen were pitting their power and popularity against that of the President. Historian McPherson wrote: “That final sentence provides a key to understanding this astonishing attack on a president by leaders of his party. The reconstruction issue had become tangled with intraparty political struggles in the Republican presidential campaign of 1864. The Wade-Davis manifesto was part of a movement to replace Lincoln with a candidate more satisfactory to the radical wing of the party.”22 But the Wade-Davis duo had overplayed their hand. According to historian T. Harry Williams, “The manifesto exploded in Washington with sudden violence, throwing ‘politicians of every stamp into the wildest confusion,’ as one reporter wrote. Old [Count Adam] Gurowski chortled with elation: ‘Better late than never. Two men call the people and Mr. Lincoln to their respective senses.’ The [Benjamin] Butler forces exulted at the evident terror which the document created in the administration camp. Montgomery Blair was reported to have cried bitterly, ‘We have Lee & his ___ on one side, and Henry Winter Davis & Ben Wade and all such hell cats on the other. The manifesto excited the Jacobins to new hope: they felt confident now of destroying Lincoln.”23

According to historian Gerald S. Henig, “Republican reaction to the manifesto came swiftly – and most of it was unfavorable. ‘Everywhere, north, east, south, and west,’ as former Ohio representative Albert G. Riddle put it, ‘the masses were with Mr. Lincoln.’ Even Greeley’sTribune, which published the manifesto, refused to support it. George William Curtis, the editor of Harper’s Weekly, condemned its ‘ill-tempered spirit,’ and suggested that it was clear proof of the ‘unfitness’ of both Wade and Davis as ‘grave counselors in a time of national peril.’ Henry Raymond of the New York Times went even further. ‘The real crime of President Lincoln in their eyes,’ Raymond insisted, ‘is not that he has in any way or to any extent invaded the rights of Congress, or usurped power not conferred upon him by the Constitution, but that he has evinced a purpose to restore the states to their old allegiance, and the Union to its old integrity, upon terms more in conformity with the spirit of Republican Government than those which they seek to impose. His invasions of Congressional right, – his usurpations of Executive power, – would not disturb them if they were practiced on their behalf, and for the furtherance of their schemes.'”24

“Much of the party leadership and press condemned the manifesto and it ‘rallied his friends to his support with that same intense form of energy which springs from the instinct of self-preservation. The Wade-Davis Manifesto probably did more harm to its authors than to Lincoln,” wrote David E. Long in The Jewel of Liberty.25 Historian T. Harry Williams wrote: “The president’s leading newspaper champion, Raymond’s Times, betrayed its fright in an angry editorial which screamed that Wade and Davis were dangerous revolutionary radicals: ‘They have sustained the war, not as a means of restoring the Union, but to free the slaves, seize the lands, crush the spirit, destroy the rights and blot out forever the political freedom of the people inhabiting the Southern States.”26 Harper’s Weekly Editor George Tichenor Curtis, wrote: “We have read with pain the manifesto of Messrs. Wade and Winter Davis, not because of its envenomed hostility to the President, but because of its ill-tempered spirit, which proves conclusively the unfitness of either of the gentlemen for grave counselors in a time of national peril.”27

Historian T. Harry Williams wrote: “The elation of the Jacobins was unfounded, as they might have realized if they had studied the press reactions to the manifesto more carefully. Greeley cautiously pronounced it ‘a very able and caustic protest,’ but he went no farther and added that he did not regret the veto of the Wade-Davis bill. Every [the New York Evening Post‘s William Cullen] Bryant ventured only a guarded approval. An overwhelming majority of the Republican newspapers denounced the authors as wreckers of party unity, and repudiated the sentiments in the manifesto. The great organ of radicalism in the West, the Chicago Tribune, condemned them bitterly. So did the Detroit journal which had been Chandler’s staunchest supporter in Michigan politics. Led by the Forney papers, the conservative Eastern press rallied to the president.”28

The New York editors were such a diverse lot that they had trouble making common trouble against President Lincoln and his policies. Press reaction to the Wade-Davis Manifesto was diverse, according to historian Hans Trefousse: “Although the New York Tribune had published the Manifesto in its own pages, it refused to support it, and it was not surprising that the document was widely attacked. Back home in Jefferson, [Ohio,] the Ashtabula Sentinel, calling it ‘ill-tempered and improper,’ expressed the opinion that nothing could have been more welcome to the opposition. The National Anti-Slavery Standard deplored it, and since the Copperhead New York World congratulated the country ‘that the two Republicans have been found willing at last to resent the encroachments of the executive,’ the New York Times felt justified in stating, ‘It is by far the most effective Copperhead campaign document thus far issued.'”29

Reaction from the nation’s Chief Executive in Washington was more muted. Friend Ward Hill Lamon recalled: “Mr. Lincoln, when asked if he had seen the Wade-Davis manifesto, the [Wendell] Phillips speech, etc., replied: ‘No, I have not seen them, nor do I care to see them. I have seen enough to satisfy me that I am a failure, not only in the opinion of the people in rebellion, but of many distinguished politicians of my own party. But time will show whether I am right or they are right, and I am content to abide its decision. I have enough to look after without giving much of my time to the consideration of who shall be my successor in office.”30 On August 6, Navy Secretary Gideon Welles recorded what happened at a Cabinet meeting that day:

I remarked that I had seen the Wade and Winter Davis protest. He said, Well, let them wriggle, but it was strange that Greeley, whom they made their organ in publishing the protest, approved his course and therein differed from the protestants. The protest is violent and abusive of the President, who is denounced with malignity for what I deem the prudent and wise omission to sign a law prescribing how and in what way the Union shall be reconstructed. There are many offensive features in the law, which is, in itself, a usurpation and abuse of authority. How or in what way or ways the several States are to put themselves right – retrieve their position – is in the future and cannot well be specified. There must be latitude given, and not a stiff and too stringent policy pursued in this respect by either the Executive or Congress. We have a Constitution, and there is still something in popular government.

In getting up this law it was as much an object of Mr. Winter Davis and some others to pull down the Administration as to reconstruct the Union. I think they had the former more directly in view than the latter. Davis’s conduct is not surprising, but I should not have expected that Wade, who has a good deal of patriotic feeling, common sense, and a strong, though coarse and vulgar, mind, would have lent himself to such a despicable assault on the President. 31

Two days later, Welles was again at a Cabinet meeting: “The President, in a conversation with Blair and myself on the Wade and Davis protest, remarked that he had not, and probably should not read it. From what was said of it he had no desire to, could himself take no part in such a controversy as they seemed to wish to provoke. Perhaps he is right, provided he has some judicious friend to state to him what there is really substantial in the protest entitled to consideration without the vituperative asperity. The whole subject of what is called reconstruction is beset with difficulty, and while the executive has indicated one course and Congress another, a better and different one than either may be ultimately pursued. I think the President would have done well to advise with his whole Cabinet in the measures he has adopted, not only as to reconstruction or reestablishing the Union, but as to this particular bill and the proclamation he has issued in regard to it.”32

The Manifesto’s “greatest beneficiary, however, was the Democratic party. Anti-administration editors and politicians made good use of the document as evidence of Lincoln’s dishonesty and incapacity. Indeed, as the New York Times pointed out, the Manifesto ‘furnished the Copperheads with powder and ball for the whole campaign,” wrote Henry Winter Davis’s biographer, Gerald S. Henig. “From all perspectives, then, it was plainly evident that Davis had committed a major blunder. Even supporters in his own district and state lashed out at him for his ill-tempered and fool-hardy actions. “In Maryland,’ he told Du Pont, “they are firing away at me.”33

The Manifesto “took the heart out of the conservatives,” according to T. Harry Williams. “Welles could think of no better retort than to charge the Wade had been bitten by the presidential bug. Blair feared that Lincoln could not overcome the force of the attack unless ‘we meet with reasonable success in arms.’ The alarm of the administration supporters jumped higher at a rumor that Wade and Davis would follow up their protest with a demand in Congress for the impeachment of the president.”34

August was indeed a bad month for President Lincoln’s supporters – for reasons mostly unrelated to the Wade-Davis Manifesto. His reelection possibilities seemed to have tanked and his reelection supporters were frantic. Navy Secretary Welles wrote in his diary: “The assaults of these men on the Administration may break it down. They are, in their earnest zeal on the part of some, and ambition and malignity on the part of others, doing an injury that they cannot repair. I do not think Winter Davis is troubled in that respect, or like to be, but I cannot believe otherwise of Wade and others; yet the conduct of Wade for some time past, commencing with the organization of the present Congress in December last, after the amnesty proclamation and conciliatory policy of reconstruction, been in some respects strange and difficult to be accounted for, except as an aspiring factionalist. I am inclined to believe that he has been bitten with the Presidential fever, is disappointed, and in his disappointment, with a vague, indefinite hope that he may be successful, prompted and stimulated not only by Davis but [House Speaker Schuyler] Colfax, he has been flattered to do a foolish act.”35

According to Secretary Welles: “H. Winter Davis has a good deal of talent but is rash and uncertain. There is scarcely a more ambitious man, and no one that cannot be more safely trust. He is impulsive and mad and has been acute and contriving in this whole measure and has drawn Wade, who is ardent, and others into it.”36 Wade biographer Hans Trefousse wrote: “Lincoln himself was also depressed by the Manifesto. It was sad ‘to be wounded in the house of one’s friends,’ as he put it, and he wondered whether Wade and Davis intended to oppose his election openly. But the President realized that the authors had probably overshot their mark.”37

Through the crisis, the President maintained his sense of humor, according to artist Francis B. Carpenter: “When he had thought profoundly, however, upon certain measures, and felt sure of his ground, criticism, either public or private, did not disturb him. Upon the appearance of what was known as the ‘Wade and Davis manifesto,’ subsequent to his renomination, an intimate friend and supporter, who was very indignant that such a document should have been put forth just previous to the presidential election, took occasion to animadvert very severely upon the course that prompted it. ‘It is not worth fretting about,’ said the President; ‘it reminds me of an old acquaintance, who, having a son of a scientific turn, bought him a microscope. The boy went around, experimenting with his glass upon everything that came in his way. One day, at the dinner-table, his father took up a piece of cheese. ‘Don’t eat that, father,’ said the boy; ‘it is full of wrigglers.’ ‘My son,’ replied the old gentleman, taking, at the same time, a huge bite, ‘let ’em wriggle; I can stand it if they can.'”38

Such humor was a useful counterpart to the criticism which President Lincoln repeatedly faced. “Lincoln’s story was apt. He could stand the Manifesto, as the reaction of the country was beginning to show,” wrote historian Hans L. Trefousse. “His supporters in Washington did not even bother to print the document in their Daily Morning Chronicle; the Tribune‘s strictures upon it made much better copy. And when, three days later, news of Farragut’s victory at Mobile reached the North, they could well afford to disregard the Manifesto altogether. The skies are again brightening,’ they wrote.”39

Footnotes

- Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, p. 438.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 357.

- Hans Trefousse, Benjamin Franklin Wade: Radical Republican from Ohio, p. 222.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865, p. 83-84.

- Hans L.Trefousse, Benjamin Franklin Wade: Radical Republican from Ohio, p. 221.

- Bruce Tap, Over Lincoln’s Shoulder, p. 218.

- John G. Nicolay and John Hay, Abraham Lincoln: A History, Volume VIII, p. 433-34.

- Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger, editor, Inside Lincoln’s White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 217-218 (ca. July 4, 1864).

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 321.

- Gerald S. Henig, Henry Winter Davis, p. 212.

- Allan Nevins, War for the Union: The Organized War to Victory, 1864-1865, p. 86.

- Richard Nelson Current, Old Thad Stevens, p. 201.

- David Donald, editor, Inside Lincoln’s Cabinet: The Civil War Diaries of Salmon P. Chase, p. 232-233 (July 6, 1864).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume VII, p. 433-434 (July 8, 1864).

- Gerald S. Henig, Henry Winter Davis, p. 213.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 357.

- Hans L.Trefousse, Benjamin Franklin Wade: Radical Republican from Ohio, p. 223-224.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 357.

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 713.

- Gerald S. Henig, Henry Winter Davis: Antebellum and Civil War Congressman from Maryland, p. 215-216.

- Detroit Post and Tribune, Zachariah Chandler: An Outline Sketch of His Life and Public Services, p. 270-271.

- James M. McPherson, Battle Cry for Freedom, p. 713.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 325.

- Gerald S. Henig, Henry Winter Davis: Antebellum and Civil War Congressman from Maryland, p. 216.

- David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln’s Re-election and the End of Slavery, p. 185.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 325.

- David E. Long, The Jewel of Liberty: Abraham Lincoln’s Re-election and the End of Slavery, p. 186.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 326.

- Hans Trefousse, Benjamin Franklin Wade, p. 225-227.

- Ward Hill Lamon, Recollections of Abraham Lincoln, p. 189-191.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 94-95 (August 6, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 98 (August 8, 1864).

- Gerald S. Henig, Henry Winter Davis, p. 219.

- T. Harry Williams, Lincoln and the Radicals, p. 325.

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 96 (August 6, 1864).

- Gideon Welles, Diary of Gideon Welles, Volume II, p. 95 (August 6, 1864).

- Hans L. Trefousse, Benjamin Franklin Wade, p. 228.

- Francis B. Carpenter, The Inner Life of Abraham Lincoln: Six Months at the White House, p. 145.

- Hans L. Trefousse, Benjamin Franklin Wade, p. 228-229.

Visit

Zachariah Chandler (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Salmon P. Chase (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Henry Winter Davis (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Horace Greeley (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Horace Greeley (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Horace Greeley (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Ward Hill Lamon (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Ward Hill Lamon (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Henry J. Raymond (Mr. Lincoln and New York)

Thaddeus Stevens (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Charles Sumner (Mr. Lincoln and Friends)

Charles Sumner (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)

Gideon Welles (Mr. Lincoln’s White House)