Mr. Lincoln’s speech-making continued to have a great political effect during the post-1858 period – inside and outside of his home state of Illinois. Indianian Hugh McCullough, who would become the third Secretary of the Treasury under President Lincoln, later recalled: “The first time I saw and heard him was at Indianapolis, shortly after the conclusion of his debate with Mr. Douglas. Careless of his attire, ungraceful in his movements, I thought as he came forward to address the audience that was the most ungainly figure I had ever seen upon a platform. Could this be Abraham Lincoln whose speeches I had read with so much interest and admiration – this plain, dull-looking man the one who had successfully encountered in debate one of the most gifted speakers of his time? The question was speedily answered by the speech. The subject was slavery – its character, its incompatibility with Republican institutions, its demoralizing influences upon society, its aggressiveness, its rights as limited by the Constitution; all of which were discussed with such clearness, simplicity, earnestness, and force as to carry me with him to the conclusion that the country could not long continue part slave and part free – that freedom must prevail throughout the length and breadth of the land, or that the great Republic, instead of being the home of the free and the hope of the oppressed, would become a by-word and a reproach among the nations.”1

During 1859, Mr. Lincoln made several campaign speeches on the slavery theme in Illinois and nearby Midwestern states. For example, he addressed a group of Chicago Republicans in March 1859, concluding his remarks:

I do not wish to be misunderstood upon this subject of slavery in this country. I suppose it may long exist, and perhaps the best way for it come to an end peaceably is for it to exist for a length of time. But I say that the spread and strengthening and perpetuation of it is an entirely different proposition. There we should in every way resist it as a wrong, treating it as a wrong, with fixed idea that it must and will come to an end. If we do not allow ourselves to be allured from the strict path of our duty by such a device as shifting our ground and throwing ourselves into the rear of a leader who denies our first principle, denies that there is an absolute wrong in the institution of slavery, then the future of the Republican cause is safe and victory is assured. You Republicans of Illinois have deliberately taken your ground; you have heard the whole subject discussed again and again; you have stated your faith, in platforms laid down in a State Convention, and in a National Convention, you have heard and talked over and considered it until you are now all of opinion that you are on a ground of unquestionable right. All you have to do is to keep the faith, to remain steadfast to the right, to stand by your banner. Nothing should lead you to leave your guns. Stand together, ready, with match in hand. Allow nothing to turn you to the right or to the left. Remember how long you have been in setting out on the true course; how long you have been in setting out on the true course; how long you have been in getting your neighbors to understand and believe as you now do. Stand by your principles; stand by your guns; and victory complete and permanent is sure at the last.2

In April 1859, Mr. Lincoln summarized the strange shift in party principles that occurred over the previous seven decades. He did so in a letter to several Boston Republicans in which he declined an invitation to speak there:

Bear in mind that about seventy years ago, two great political parties were first formed in this country, that Thomas Jefferson was the head of one of them, and Boston the head-quarters of the other, it is both curious and interesting that those supposed to descend politically from the party opposed to Jefferson, should now be celebrating his birth-day in their own original seat of empire, while those claiming political descent from him have nearly ceased to breathe his name everywhere.

Remembering too, that the Jefferson party were formed upon their supposed superior devotion to the personalrights of men, holding the rights of property to be secondary only, and greatly inferior, and then assuming that the so-called democracy of to-day, are the Jefferson, and their opponents, the anti-Jefferson parties, it will be equally interesting to note how completely the two have changed hands as to the principle upon which they were originally supposed to be divided.

Lincoln concluded: “This is a world of compensations; and he who would be no slave, must consent to have no slave. Those who deny freedom to others, deserve it not for themselves; and, under adjust God, can not long retain it.”3

In June, Mr. Lincoln addressed another correspondent who suggested the “nationalization of slavery” to which Mr. Lincoln refused to accede. Mr. Lincoln wrote:

From the passage of the Nebraska-bill up to date, the Southern opposition have constantly sought to gain an advantage over the rotten democracy, by running ahead of them in extreme opposition to, and vilifacation [sic], and misrepresentation of black republicans. It will be a good deal, if we fail to remember this in malice, (as I hope we shall fail to remember it;) but it is altogether too much to ask us to try to stand with them on the platform which has proved altogether insufficient to sustain them alone.

If the rotten democracy shall be beaten in 1860, it has to be done by the North; no human invention can deprive them of the South. I do not deny that there are as good men in the South as the North; and I guess we will elect one of them if he will allow us to do so on Republican ground. I think there can be no other ground of Union. For my single self I would be willing to risk some Southern men without a platform; but I am satisfied that is not the case with the Republican party generally.4

In September 1859 Mr. Lincoln went to Ohio and Indiana to campaign for Republican candidates, refute Stephen Douglas’s propagation of popular sovereignty, and fight the extension of slavery. Mr. Lincoln told a Columbus audience:

Looking at these things, the Republican party, as I understand its principles and policy, believe that there is great danger of the institution of slavery being spread out and extended, until it is ultimately made alike lawful in all the States of this union; so believing, to prevent that incidental and ultimate consummation, is the original and chief purpose of the Republican organization. I say ‘chief purpose’ of the Republican organization; for it is certainly true that if the national House shall fall into the hands of the Republicans, they will have to attend to all the others matters of national house-keeping, as well as this. This chief and real purpose of the Republican party is eminently conservative. It proposes nothing save and except to restore this government to its original tone in regard to this element of slavery, and there to maintain it, looking for no further change, in reference to it, than that which the original framers of the government themselves expected and looked forward to.

The chief danger to this purpose of the Republican party is not just now the revival of the African slave trade, or the passage of a Congressional slave code, or the declaring of a second Dred Scott decision, making slavery lawful in all the States. These are not pressing us just now. They are not quite ready yet. The authors of these measures know that we are too strong for them; but the will be upon us in due time, and we will be grappling with them hand to hand, if they are not now headed off. They are not now the chief danger to the purpose of the Republican organization, but the most imminent danger that now threatens that purpose is that insidious Douglas Popular Sovereignty. This is the miner and sapper. While it does not propose to revive the African slave trade, nor to pass a slave code, nor to make a second Dred Scott decision, it is preparing us for the onslaught and charge of these ultimate enemies when they shall be ready to come on and the word of command for them to advance shall be given. I say this Douglas Popular Sovereignty – for there is a broad distinction, as I now understand it, between that article and a genuine popular sovereignty.

I believe there is a genuine popular sovereignty. I think a definition of genuine popular sovereignty, in the abstract, would be about this: That each man shall do precisely as he pleases with himself, and with all those things which exclusively concern him. Applied to government, this principle would be, that a general government shall do all those things which pertain to it, and all the local governments shall do all those things which pertain to it, and all the local governments shall do precisely as they please in respect to those matters which exclusively concern them. I understand that this government of the United States, under which we live, is based upon this principle; and I am misunderstood if it is supposed that I have any war to make upon that principle.5

In Indianapolis three days later, Mr. Lincoln spoke of the dignity of labor: “The speaker himself had been a hired man twenty-eight years ago. He didn’t think he was worse off than a slave. He might not be doing as much good as good as he could, but he was now working for himself. He thought the whole thing was a mistake. There was a certain relation between capital and labor, and it was proper that it existed. Men who were industrious and sober, and honest in the pursuit of their own interests, should after a while accumulate capital, and after that should be allowed to enjoy it in peace, and if they chose, when they had accumulated capital, to use it to save themselves from actual labor and hire other people to labor for them, it was right. They did not wrong the man they employed, for they found men who have not their own land to work upon or shops to work in, and who were benefitted by working for them as hired laborers, receiving their capital for it.”6

At the end of the month in Wisconsin, Mr. Lincoln returned to the theme of free labor. He told an audience: “The prudent, penniless beginner in the world, labors for wages awhile, saves a surplus with which to buy tools or land, for himself; then labors on his own account another while, and at length hires another new beginner to help him. This, say its advocates, is free labor – the just and generous, and prosperous system, which opens the way for all – gives hope to all, and energy, and progress, and improvement of condition to all. If any continue through life in the condition of the hired laborer, it is not fault of the system, but because of either a dependent nature which prefers it, or improvidence, folly, or singular misfortune. I have said this much about the elements of labor generally, as introductory to the consideration of a new phase which that element is in process of assuming. The old general rule was thateducated people did not perform manual labor. They managed to eat their bread, leaving the toil of producing it to the uneducated. This was not an insupportable evil to the working bees, so long as the class of drones remained very small. But now, especially in these free States, nearly all are educated – quite too nearly all, to leave the labor of the uneducated, in any wise adequate to the support of the whole. It follows from this that henceforth educated people must labor. Otherwise, education itself would become a positive and intolerable evil. No country can sustain, in idleness, more than a small percentage of its numbers. The great majority must labor at something productive. From these premises the problem springs, ‘How can labor and educationbe the most satisfactorily combined?'”7

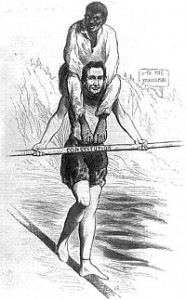

The next day in Janesville, Wisconsin, Mr. Lincoln returned to the legacy of the Declaration of Independence in establishing the rights of blacks as well as white: “Mr. Lincoln said that he had failed to find a man who five years ago had expressed it his belief that the declaration of independence did not embrace the colored man. But the public mind had become debauched by the popular sovereignty dogma of Judge Douglas. The first step down the hill is the denial of the negro’s rights as a human being. The rest comes easy. Classing the colored race with brutes frees from all embarrassment the idea that slavery is right if it only has the endorsement the idea that slavery is right if it only has the endorsement of the popular will. Douglas has said that in a conflict between the white man and the negro, he is for the white man, but in a conflict between the white and the negro, he is for the white man; but in a conflict between the negro and the crocodile, he is for the negro. Or the matter might be put in this shape. As the white man is to the negro, so is the negro to the crocodile! (Applause and laughter.) But the idea that there was a conflict between the two races, or that the freedom of the white man was insecure unless the negro was reduced to a state of abject slavery, was false and that as long as his tongue could utter a word he would combat that infamous idea. There was room for all races and as there was no conflict so there was no necessity of getting up an excitement in relation to it.8

In early December, Mr. Lincoln went to Kansas to address some Republican rallies in Leavenworth. He began one speech by saying: “Ladies and Gentlemen: You are, as yet, the people of Territory; but you probably soon will be the people of State of the Union. Then you will be in possession of new privileges, and new duties will be upon you. You will have to bear a part in all that pertains to the administration of the National Government. That government, from the beginning has had, has now, and must continue to have a policy in relation to domestic slavery. It cannot, if it would, be without a policy upon that subject. And that policy must, of necessity, take one of two directions. It must deal with the institution as being wrong or as not being wrong.’9

However, these letters and speeches were far overshadowed by the February 27, 1860 Cooper Institute speech in New York City. “Lincoln’s theme was a formulation of the principles on which the Republican party should face the electorate in 1860; but instead of attempting a full coverage of issues he spoke only of the slavery question. Federal slavery restriction, he urged, was consistent with the doctrines of the fathers. All that Republicans asked to leave slavery where the fathers left it, as an evil to be tolerated but not extended,” wrote Lincoln biographer James G. Randall.10 According to Randall, “Other speeches by Lincoln in this general period were in the same vein. Though not mere repetition, they struck the same note, emphasizing that slavery was wrong, but hoping for a cure, together with an abatement of factional strife and controversy.”11

Historian Allan Nevins wrote that “fault could have been found with Lincoln for not saying what he wished done with slavery once it had been bound within an immovable ring – for he certainly hoped for some gradual type of national action. And once more, Lincoln could have replied that one step at a time was enough, and that if the South agreed to restriction it would by implication agree to reasonable further measures. He said he would not act rashly.”12 In his speech in Hartford on March 5, Mr. Lincoln expressed his caution:

They tell us that they desire the people of a territory to vote slavery out or in as they please. But who will form the opinion of the people there? The territories may be settled by emigrants from the free States, who will go there with this feeling of indifference. The question arises, ‘slavery or freedom?’ Caring nothing about it, they let it come in, and that is the end of it. It is the surest way of nationalizing the institution. Just as certain, but more dangerous because more insidious; but it is leading us there just as certainly and as surely as Jeff. Davis himself would have us go.

For instance, out in the street, or in the field, or on the prairie I find a rattlesnake. I take a stake and kill him. Everybody would applaud the act and say I did right. But suppose the snake was in a bed where the children were sleeping. Would I do right to strike him there? I might hurt the children; or I might not kill, but only arouse and exasperate the snake, and he might bit the children. Thus, by meddling with him here, I would do more hurt than good. Slavery is like this. We dare not strike at it where it is. The manner in which our constitution is framed constrains us from making war upon it where it already exists. The question that we now have to deal with is, ‘Shall we be acting right to take this snake and carry it to a bed where there are children?’ The Republican party insists upon keeping it out of the bed.13

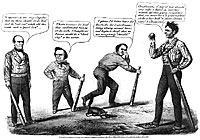

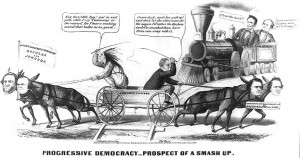

The 1860 presidential election threatened to split the country over the issue of slavery. Historian William E. Gienapp wrote: “Prior to the rise of the Republican party, the two major parties were national organizations, with a constituency drawn from both sections. The need to agree on a national platform promoted the idea of compromise and sectional harmony. As a result, parties often emphasized the personalities of presidential candidates over issues and channeled popular emotions behind candidates and party symbols rather than rigid ideologies.”14 The Republican Party needed to tred lightly on the slavery issue during the campaign. Had Mr. Lincoln been perceived as too radical on slavery, he would not have been elected President in 1860. The focus of Democratic efforts in that campaign was to paint Mr. Lincoln as dangerously radical. The Republican strategy was to appear as benign as possible.

Republicans had come tantalizing close to winning the Presidency on the party’s first national contest in 1856. Although it failed with the candidacy of explorer John C. Fremont, it did briefly win control of the House of Representatives. Gienapp wrote: “The Republican party differed from other third parties in that it had to control Congress and the presidency to achieve its goals. Republicans could first organize at the state level, but they had to ultimately create a strong party on the national level in order to stop the expansion of slavery and limit the political power of the South. Republican organizers, however, enjoyed two advantages over new parties today. First, congressional incumbents lacked the decisive advantages that they now enjoy in terms of name recognition, campaign funds, and media exposure. Moreover, most districts adhered to some sort of rotation rule, so congressional terms of service were shorter and turnover higher. Because they did not have to challenge mostly well-financed, deeply entrenched incumbents, Republicans were able to quickly elect a number of congressmen who served as the nucleus for the developing national party organization.”15

Even before Mr. Lincoln’s nomination by the Republican Party at its Chicago convention in mid-May, anti-slavery advocates like New York TribuneEditor Horace Greeley realized the necessity of moderation. Biographer Jeter Allen Iseley wrote, “Greeley’s anxiety to halt the antislavery tornado may be seen in the conservative platform drawn up at Chicago. He served on the resolutions committee, and the document which emerged shows his strong influence. He later affirmed that he labored ‘long and earnestly’ to divest this party pronouncement of all features ‘needlessly offensive or irritating’ to the south. Specifically, he claimed credit for having blocked ‘the requirement that Congress shall positively prohibit Slavery in every Territory whether there be or be not a possibility of its going thither.”16 The Republican platform stated “the new dogma, that the Constitution carries slavery into all the Territories, is a dangerous political heresy, revolutionary in tendency and subversive of the peace and harmony of country; that the normal condition of all the Territories is that of freedom; that neither Congress, the Territorial Legislature, nor any individual can give legal existence to slavery in any Territory; that the opening of slave trade would be a crime against humanity.”17

Slavery, however, was a two-edged sword. Northerners didn’t like slavery, but they also didn’t like former slaves. Historian Allan Nevins wrote: “Indiana also took the Negro question with intense seriousness. The State in 1860 had about 11,000 colored people, and many thought that number quite enough. When the Emancipation Proclamation appeared, the New Albany Sentinel and other papers predicted that a deluge of lazy, helpless, and thriftless freedmen would roll across poor Hoosierdom. In Illinois, too, where the latest census had reported a colored population of 7,628, the subject had become painful as soon as the capture of Donelson and Nashville brought a host of refugee slaves into Cairo. David Davis warned the President in mid-October [1862] that if they infiltrated into central Illinois, they would do the party grave injury in the election, and Governor Yates telegraphed Lincoln to the same effect. Since 1853, Illinois had on its statute books a law which imposed a heavy fine on every Negro, slave or free, who entered the State, and though many regarded it as unconstitutional, in certain localities it had been enforced. Now, shortly before election, the Secretary of State prohibited any further entry.18

Democrats sought to limit Mr. Lincoln’s appeal in 1860 by portraying him and running mate Hannibal Hamlin as black Republicans who would overthrow the existing social order. Historian Richard H. Sewell wrote: “In the end, Democratic attempts to smear Lincoln …brought even some of the Republicans’ sharpest critics around. H. Ford Douglass, for one, changed his tune in the closing days of the campaign. ‘I love everything the South hates,’ he told a rally in Boston, ‘and since they have evidenced their dislike of Mr. Lincoln, I am bound to love you Republicans with all your faults.’ Thus, ironically, did eligible Northern blacks vote ‘almost solidly’ for a presidential candidate who disapproved their right to do so.”19 Historian Sewell wrote: “As a rule, radical white abolitionists remained even more critical than blacks of the Republican party’s failings. The Republicans’ narrow, non-extension platform, their ‘excessive prudence,’ their shameful scrambling to dissociate themselves from genuine abolitionists, their tendency to undercut more radical activity, and their neglect of Negro rights all reinforced the conviction of avowed abolitionists that Republicanism was an exceedingly unreliable antislavery force.”20

Mr. Lincoln himself said virtually nothing publicly on slavery or any other political issue after his Cooper Union speech in late February and his subsequent speaking tour through New England in early March. But leaders of both major parties were at work spreading political conspiracy theories about the intentions of their opponents. Historian David W. Blight wrote: “As several historians have portrayed it, the secession crisis of 1860-61 was a time of great fear. The deepest anxieties of northerners and southerners were at stake, as both sections came to view each other in conspiratorial terms. By this time, the notions of a ‘Slave Power’ conspiracy in northern minds and a ‘Black Republican’ conspiracy in southern minds each had long histories. The political process that had produced such conspiratorial consciousness, in its rational and irrational dimensions, was something that blacks, slave and free, had observed, interpreted, and helped to shape.”21

The political process broke down on December 20, 1860 when South Carolina officially seceded. Its Ordinance of Secession clearly indicated that South Carolina blamed slavery for its secession. It stated that the “ends for which this Government was instituted have been defeated, and the Government itself has been destructive of them by the action of the non-slaveholding States. Those States have assumed the right of deciding upon the propriety of our domestic institutions; and have denied the rights of property established in fifteen of the States and recognized by the Constitution; they have denounced as sinful the institution of Slavery, they have permitted the open establishment among them of societies, whose avowed object is to disturb the peace of and purloin the property of the citizens of other States. They have encouraged and assisted thousands of our slaves to leave their homes; and those who remain, have been incited by emissaries, books, and pictures, to servile insurrection…”22

Privately, President-elect Lincoln urged colleagues to remain firm in the face of the secessionist threat, but publicly, he said little until his Inauguration in early March 1861. He did send signals, however. On December 22, for example, the New York Tribune reported: “We are enabled to state in the most positive terms that Mr. Lincoln is utterly opposed to any concession or compromise that shall yield one iota of the position occupied by the Republican Party on the subject of slavery in the territories, and that he stands now, as he stood on May last, when he accepted the nomination for the Presidency, square upon the Chicago platform.”23

Mr. Lincoln rejected efforts to weaken the Republican opposition to spread of slavery into the territories. Historian George Milton Fort wrote that President James Buchanan sent General Duff Green to Springfield to persuade President-elect Lincoln to work on a compromise with the South. “Green reached Springfield on December 28. Lincoln refused the invitation to come to Washington, and explained why he could not accept the Crittenden plan. While the restoration of the Missouri Compromise line ‘would quiet for the present the agitation of the slavery question,’ sectional difficulties would soon be renewed by the seizure and attempted annexation of Mexico. The real question at issue between the North and the South was slavery ‘propagandism’; the Republican party was opposed to the south upon that issue and he was with his own party; it had elected him and he ‘intended to sustain his party in good faith. General Green appealed for a letter from Lincoln agreeing that Congress should refer ‘the measures for the preservation of the Union to the action of the people in the several States.’ Lincoln promised such a letter the next morning.’ No letter came and Green returned to Washington bitter over his experiences.”24

The stage was set for the Civil War and emancipation.

Footnotes

- Allen Thorndike Rice, editor, Reminiscences of Abraham Lincoln, p. 414 (Hugh McCullough).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume III, p. 365-370 (Speech at Chicago, Illinois, March 1, 1859).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume III, p. 376 (Letter to Henry L. Pierce and others, April 6, 1859).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume III, p. 387-388 (Letter to Nathan Sargent, June 23, 1859).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume III, p. 400-425 (Speech at Columbus, Ohio, September 16, 1859).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume III, p. 463-470 (Speech at Columbus, Ohio, September 19, 1859).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume III, p. 471-482 (Address Before the Wisconsin State Agricultural Society, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, September 30, 1859).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume III, p. 484-486 (Speech at Janesville, Wisconsin. October 1, 1859).

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume III, p. 497-502 (Speech at Leavenworth, Kansas, December 3, 1859).

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume I, p. 136.

- James G. Randall, Lincoln the President: Springfield to Gettysburg, Volume I, p. 137.

- Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to the Civil War, 1859-1861, p. 243.

- Roy P. Basler, editor, The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, Volume IV, p. 2-8 (Speech in Hartford, March 5, 1860).

- Gabor S. Boritt, editor, Why the Civil War Came, p. 106 (William E. Gienapp, “The Political System and the Coming of the Civil War”).

- Gabor S. Boritt, editor, Why the Civil War Came, p. 111 (William E. Gienapp, “The Political System and the Coming of the Civil War”).

- Jeter Allen Iseley, Horace Greeley and the Republican Party, 1863-1861: A Study of the New York Tribune, p. 288.

- William H. Herndon and Jesse W. Weik, Herndon’s Life of Abraham Lincoln, p. 375.

- Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, War Becomes Revolution, 1862-63, p. 308.

- Richard H. Sewell, Ballots for Freedom: Antislavery Politics in the United States, 1837-1860, p. 338.

- Richard H. Sewell, Ballots for Freedom: Antislavery Politics in the United States, 1837-1860, p. 339.

- Gabor S. Boritt, editor, Why the Civil War Came, (David W. Blight, “African-Americans and the Coming of the Civil War”).

- Kenneth Stampp, The Causes of the Civil War, p. 42.

- David M. Potter, Lincoln and His Party in the Secession Crisis, p. 161.

- George Milton Fort, The Eve of Conflict: Stephen A. Douglas and the Needless War, p. 528.